May 13, 2005

Detention, refugees, homo sacer

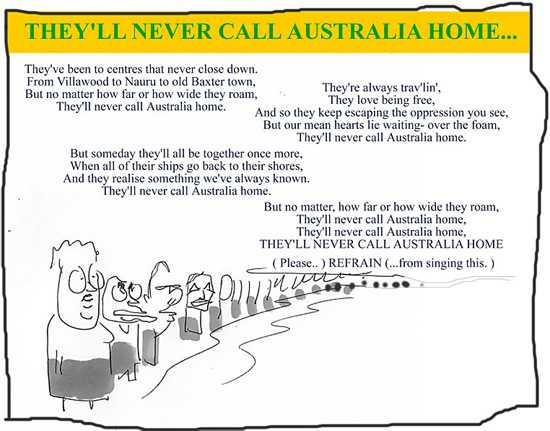

The national security state presupposes strict border controls, mandatory detention of asylum seekers and illegal immigrants, a network of privately run mandatory detention camps, and the camps being run on prison lines. This system and governance is premised on saying no to the movement of illegal migration into Australia, cutting the flow of asylum seekers, and dealing with the asylum seekers in terms of punitive crime and punishment regime. The history of the resistance to immigration in Australia is a long, grim and powerful in this country -- it is a history of legal constraint, of walls descending, of bitter prejudice, racism and vigilantism.

Matt Golding

Some in Australia are now questioning the way the Department of Immigration (DIMIA) goes about stopping the traffic; the way it governs those imprisoned and the way it deports those stateless people it has classified as illegal immigrants. Many liberals are uncomfortable with the harshness of the regime and the cowboy culture of DIMIA. The illegal alien is abstractly defined as something of a specter (of terrorism) a body stripped of individual personage with no rights whose very presence on the edge of Australia's borders is troubling.

Can we frame the detention of illegal migrants (aliens) as a way to understand politics and how notions of political participation, sovereignty and the politiical "form of life" in western liberal democracies?

Is Giorgio Agamben's concept of homo sacer, which denotes a naked or bare life that is depoliticized, and exempt or excluded from the normal limits of the state. Does it indicate that it is through the exclusion of the depoliticized form of life that the politicized norm exists?

As we have seen Agamben uses Schmitt's conception of the state of exception to argue that the state of exception is born out of law suspending itself, a law that continues in relation to the state of exception announced by the sovereign. It is not that the exception is included through interdiction in that which includes it (law); rather it is 'included solely through its exclusion'–- to which Agamben coins the phrase: 'relation of exception.'

Hence, the exception is neither a fact nor a juridical case since it came into being only because of a suspension of the law. Here the crucial point is that the relation of exception is one of a 'ban.' Agamben says: 'He who has been banned is not, in fact, simply set outside the law and made indifferent to it but rather abandoned by it, that is, exposed and threatened on the threshold in which life and law, outside and inside become indistinguishable.'

Posted by Gary Sauer-Thompson at May 13, 2005 11:33 PM | TrackBackbrilliant!

Posted by: Name on May 14, 2005 09:55 AM