June 06, 2005

Giorgio Agamben: the camp in modernity

Recently two legal academics--Mirko Bagaric and Julia Clarke--from the law school at Deakin University---stated in The Age that government sanctioned torture was a 'permissable' and 'moral' action in certain circumstances justified on utilitarian grounds. It is a calculation of one tortured terrorist versus an innocent life. Peter Faris, one time head of the now defunct National Crime Authority, supported the case for torture (minimized as pulling out a finger nail) in the context of "the war of terrorism."

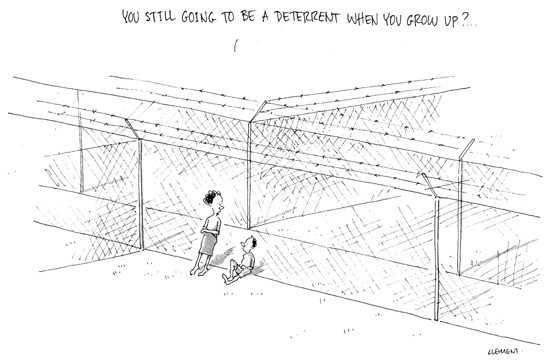

Presumably this government sanctioned torture would take place in the special detention camps within a constitutional liberal democracy:

Clement

We need to pause and take note of what is being proposed here. As Desmond Manderson says in his article, 'Another Modest Proposal' in the Review Section of Friday's Australian Financial Review:

"Torture is used to punish and humiliate dissidents, terrorists and members of ethnic minorities. It is a demonstration of what the state can do to you and its effect is to create a generalised fear about the infinite and random power of the state to destroy lives, and an intense sense of vulnerability in victim populations."

Government action and public law carry a mark of legitimation of cruelty used to enforce state power. That means state sanctioned torture is now on the political agenda.

When you couple this with Australians facing trial before U.S. military tribunals, asylum seekers languishing in camps like Baxter and Nauru, and new government legislation allowing the detention of Australian citizens themselves, then it appears that a fundamental shift has taken place in the political life on the southern continent.

What is the shift?

At this point we can turn to, and take seriously, Giorgio Agamben's argument in Homo Sacer. This argument is succinctly summarized in the concluding chapter of the text entitled 'Threshold.' The argument is organized around three main points:

1. The original political relation is the ban (the state of exception as zone of indistinction between outside and inside, exclusion and inclusion).

2. The fundamental activity of sovereign power is the production of bare life as originary political element and as threshold of articulation between nature and culture, xoe and bios.

3. Today it is not the city but rather the [concentration] camp that is the fundamental biopolitical paradigm of the West. (p. 181)

The kick is in the last bit. The concentration camp is the paradigm of modernity. It is the camp that is politically significant.

What is disturbing here is the failure of a liberal critique of the camp in Australia that those in detention suffered numerous and repeated breaches of their human rights. Australia's detention of children, HREOC says, has been "cruel, inhumane and degrading." The critique softens the harsh edges--children should not be in detention camps---but thre is an acceptance of the necessity of the camps. The merits or value of the camp as a tool of migration management is not, and cannot, be put into question. The camp is accepted as a legitimate and stable expression of state power and sovereignty.

Consider the gap between the rhetoric and reality around the camps. The contract between the Australian Commonwealth and GLS Solutions, the detention 'services provider', notes that:

"The Government takes its responsibilities for the care of all people in immigration detention seriously and expects its Services Provider to do likewise… Emphasis is placed on the sensitive treatment of the detention population which may include torture and trauma sufferers, family groups, children and unaccompanied minors, the elderly, persons with a fear of authority and persons who are seeking to engage Australia's protection obligations under the Refugee Convention." (DIMIA, 2003: Part 1, Para. 6)

Is there not an incongruity of sensitively protecting individuals incarcerated in a camp in and through an instrument of ostensible persecution?

What this indicates is that the protection of detainees in the camps is considered secondary to the greater responsibility of the state protecting citizenry and community from undesirable groups. This protection requires containing what causes anxiety to prevent the undesirables from absconding. This protection necessitates vigilance by the state. So says the liberal constitutional state.

It is the camp that should be placed into question.

Posted by Gary Sauer-Thompson at June 6, 2005 12:48 AM | TrackBack