August 20, 2005

do you sense the totalitarianism?

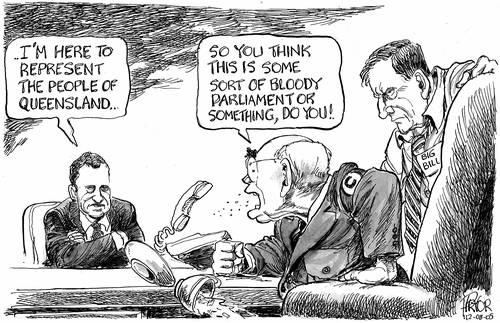

A couple of events. First a Geoff Pryor cartoon published in the Canberra Times:

The other event is the Australian Financial Review's response to the negotiations over the sale of Telstra by Barnaby Joyce and his Nationals. The Review talks in terms of reforms passed by the Howard Government's control of the Senate being marred by pork barrelling:

Now control of the Senate has opened up a whole new vista, where pork is measured in billions of dollars.There may well be a need to bring rural communications up to scratch, but the $3.1 billion ransom for Telstra's sale reflects the National's price, rather than any rigorous assessment of need.

What is underling this is a concern about the faction versus the national or public interest with the public interest associated with the sovereign will. Pork is associated with faction and national interest is associated with the neo-liberal's economic plan of privatisation.

My interpretation? The privatisation of Telstra is part of the grand plan of economic reform and faction and debate represents a form of corruption of the sovereign will.

You could say that the Review's position is that reform represents the general will of the nation--the general interest that expresses a single indivisible sovereign power--as opposed to the will of all. Consequently, the Nationals, who represent the particular interests, are the enemy within the body politic.

Do you not sense totalitarianism with the AFR position, with its desire for order? The interests of the whole must automatically and permanently be hostile to the particular regional interests of the Queensland Nationals. Don't you sense the absolutism?

I'm not sure how the AFR gets a Hobbesian conception of a single indivisible sovereign power from its economic uititaritarianism--that puzzles me. But I understand that the AFR radically devalues pluralism, political action and the public sphere.

It is not liberalism that the AFR is expressing---since liberalism affirms pluralism.

August 05, 2005

gatekeeping and digital democracy

The new gatekeepers in digital democracy---the A list or leading bloggers. They---the influential few---are the hubs of opinion-making about the ongoing revolution in media.

Jon Garfunkel at Civitas says:

"The old gatekeepers (media) and the new gatekeepers [bloggers] are not the same. Both, after all, influence what we watch and read. The difference is that the old gatekeepers do so by restricting information. The new gatekeepers do so by manipulating information cascades."

Does the gatekeeping matter?

Not really. That opinion making within the gated community is just a particular conversation on a public stage. Other people come together in other parts of the stgte to discuss common affairs, interact with one another and lay themselves open to the judgement of others.

It is the public realm, the space within which the civil conversation about public things, that is important, not the gatekeeping.

August 03, 2005

old style blogging

An old fashioned blog post: a linking to other stories with minimal commentary added.

A debate on liberal democracy over at Eurozone.

You can post several times a day doing this, moving from conversation to conversation.

I'm really not sure what the point of this style of blogging is. Is not a conversation more important? Does not a conversation require some participation to keep it going?

August 02, 2005

the salvation of democracy

George Pell, the conservative Australian Cardinal and Roman Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, gave a speech on democracy to the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty in late 2004. I found it hard to follow but I got the bit about liberal democracy is a world of 'empty secularism' that is over-focused on 'individual autonomy'. This leads to unquestioned acceptance of abortion, euthanasia and genetic experimentation, and to the claim that opposition to such things is undemocratic.

The problem with democracy is that it is neither a value-free mechanism for regulating interests, nor a good in itself; its value depends on the moral vision that it serves, and a secular democracy is lacking in moral vision. Since individualism coupled to equality and freedom is not a moral vision, he suggests 'democratic personalism'is the best form of 'normative democracy'.

By this he means a vision of human beings as centres of transcendent dignity whose existence and happiness are bound to mutual relationships. Democracy serves the flourishing of human dignity and of mutual relationships. He argues that to implement this vision we would need to change culture through persuasion and not political activism.

What he means by 'transcendent' is that we need to recognize our 'dependence on God' and place this at the centre of our system of governance. But, he asserts, 'placing democracy on this basis does not mean theocracy':

"Placing democracy on this basis does not mean theocracy.To re-found democracy on our need for others, and our need to make a gift of ourselves to them, is to bring a whole new form of democracy into being. Democratic personalism is perhaps the last alternative to secular democracy still possible within Western culture as it is presently configured."

He justifies this conception of normative democracy thus:

"The recrudescence of intolerant religion is not a problem that secular democracy can resolve, but rather a problem that it tends to engender. The past century provided examples enough of how the emptiness within secular democracy can be filled with darkness by political substitutes for religion. Democratic personalism provides another, better possibility; one that does not require democracy to cancel itself out."

July 29, 2005

'us' versus 'them'

When framed by the rhetoric of the war on terror democracy is seen as under threat and our 'way of life needs to be protected from 'them' who hates 'us' and what 'we' stand for. Any dissension or criticism of this division marks one as un-Australian and against 'us', democracy and 'our way of life.'

Jane Mummery argues that in this context there is a need for the commonality of democracy in a liberal nation-state to be informed by pluralism, dissension and undecidability.

She turns to Chanatal Mouffe to help her think through the questioning of the 'us' versus 'them' logic:

"Mouffe argues that 'the belief that a final resolution of conflicts is eventually possible is something that puts [democracy] at risk. For Mouffe (as it also is for Derrida), the democratic project is constitutively agonistic and pluralist. It marks and sustains the practice of contestation rather than any substantive consensual notion of the common good or even a 'we'... As a plurality, Mouffe insists, democracy is necessarily agonistic, insofar as the sustaining of difference is the sustaining of dissension...what this means is that the crucial problem in democratic politics for Mouffe is... the establishing of these democratic equivalences in a process she sees as the transformation of antagonism into agonism...Mouffe argues that every truly democratic community requires that both pluralism and its character of conflict are recognised as constitutive of the public sphere."

The democratic project certainly does not have a clear-cut identity or community. It doesn't need to have. Mouffe is careful to not set any specific identity to this 'we', given that it is constantly under negotiation.

One presumes that Mouffe's conception of democracy, as the agonistic plurality of determinate democratic struggle that undermines the 'us' versus 'them' logic is enframed by particular existing institutions, practices and values of liberal democracy.

July 16, 2005

publicness and speech in political life

Andrew Gibson's 'Liberalism and Utopian Publics' published in Agora deals with a key category of liberal democracy--the 'public.' How do we understand the public in a digital world? It is presupposed in a digital democracy with the conversation across and between weblogs?

Is it a realm that can still be contrasted with the private realm of the household? Is a realm that is a key part of the political life of the nation-state; a political life where we develop our human potential for reasoned speech and sense of justice?

Gibson says that a public is:

" an associational form that has become increasingly important throughout the modern period in economic, political, and cultural forms of affiliation, though it is still poorly understood. It is a flexible type of social association ideally premised on discursive openness among indefinite strangers."

A public in political life is a social association that presupposes deliberation and conversation since debate with others is a core aspect of political life. It provides the basis for a nonviolent, noncoercive form of being and acting together. Speech represents the difference between commanding and persuading and political speech (debate and deliberation) between citizens has an end in the making of a decision about which particular course of action is to be adopted.

Gibson goes to say more about the ontology of 'public'. He says:

'The constitution of the political public sphere implied the creation of a public with a greatly extended geographic range, incorporating the disparate discourses of indefinite strangers. What is concealed within this complexity is that "the" public of the public sphere was itself composed of multiple miniature publics, that is, mediated spaces of a lesser scale, which have a tighter discursive consistency, closer to the model of corporeal conversation. "Public opinion" in the singular sense is the imaginary summary point of the multiple discussion spaces it knits together in space and time, such as with the combination of a city newspaper circuit, a national radio station and a neighbourhood tavern.'

He develops two aspects of this. The first is the unity of a public:

"For a public to function, that is, for it to cohere and form a social entity that it makes sense to address, instead of remaining at the level of disjointed bits of discourse, participants have to imagine that their own discourse is an integral part of a larger conversation with indefinite strangers."

This is what we do as citizens. Even though we are strangers, we presume that we are engaged in, and a part of, a national conversation about a particular issue: mandatory detention or industrial relations reform.

Gibson says that rhe second aspect of public is public as a social entity:

'To say that a public--such as the public of the nation, of an interest group, or artistic affiliation--is a social entity means that it forms an interpretative world with its own use of language, its own normative assumptions, and sense of active belonging....The various uses of language it draws on are constituted through particular media, ranging from face-to-face conversation and artistic corporeality to print and electronic discourse. In another sense, language-use has to do with the normative horizons and structures of stranger-relationality that are implicit to preferred genres and vocabularies. These substantive horizons derive their orientation from interpretations of the ethical questions common to all cultural forms, questions of what is important and possible, or, similarly, as Warner notes, of "what can be said and about what goes without saying."'

We citizens in Australia presuppose our own interpretative political world with its shared meanings, assumptions, and ethical concerns, which is different from that of the US or Indonesia. Hence the idea of horizons, which they may overlap are still horizons.

Alas Gibson says nothing about the speech of the public in political life.

July 12, 2005

Digital Democracy

John Quiggin's presentation to the Adelaide Festival of Ideas was about the significance of blogs and Wiki, given that they restore, and actualize, the early innovation and creativity promise of the internet. Does that mean that the free spirits of creativity are resisting the threat by the bulldozers carving out property rights? John's talk did not go on to link this decentered, networked media, and co-operative Wiki way of constructing knowledge, to citizenship in a liberal democracy.

In various comments to the media the Festival organizers had linked Festival's informed discussion of public ideas to influencing government decisions so as to improve them. Though improve, or making better, was left undefined (I presume they meant something along the lines of a better life and/or a more equitable society), the organizers identified themselves as working within "the project of Enlightenment".

Mark Cully says that he is an:

"...unreconstructed beliver in the enlightenment who's very much against postmodernism. I think that there are truths which can be established. Science progresses and we get closer to the final truth on things all the time. Through science I believe in truth, I believe that informed debate gets us closer to the truth and I think if we have informed debate then there's a better chance that government's might make sensible decisions rather than if there isn't an informed debate. You can't force governments to make sensible decisions, but if you have informed debate there's a better chance of that happening."

The Habermasian understanding of the Enlightenment project argues that the public sphere is a space in which reason might prevail. This is a critical reason that is a part of the democratic tradition, not the instrumental reason of much modern economic practice that is primarily concerned with growth, wealth and prosperity.

Whether this is Quiggin's position is not clear. I am going to attribute to the Festival of Ideas, in the sense that it underpins and makes sense of their practices.

We can take Quiggin's insights a step further by asking: 'Does the internet world of blogging and Wiki change the way we understand democratic politics?' 'Do we need to rethink the modern democratic tradition to understand citizenship in a digital world?'

I suggest that we rethink the liberal political tradition. One presupposition of the Habermasian public sphere, for instance,is that private citizens will enter into the public body by leaving behind their private concerns and focusing rationally on matters of the common good. The very architecture of the Internet pushes us to think beyond the modern antinomies of public and private, rather than simply utilize the old antinomies of classical liberalism under the conditions of digital capitalism. One kind of blogging means thinking critically about public issues from within the privacy of one's home.

An implication of Quiggin's talk is that new technologies should not be treat as purely instrumental means by for pre-existing goals. Such approaches, due to the deeper cultural reconfigurations that are at stake when the material basis of communication changes. I'm interpreting Quiggin strongly, to say that we should view media technologies such as blogging as having transformative powers.

We can develop this perspective through this 1995 text by Mark Poster. He says that:

"The question that needs to be asked about the relation of the Internet to democracy is this: are there new kinds of relations occuring within it which suggest new forms of power configurations between communicating individuals? In other words, is there a new politics on the Internet?"

He says that one way to approach this question is to make a detour from the issue of technology and raise again the question of a public sphere. The question then involves gauging the extent to which Internet democracy becomes intelligible in relation to the public sphere.

Poster says that to frame the issue of the political nature of the Internet in relation to the concept of the public sphere is appropriate because of the spatial metaphor associated with the term. He adds:

"Instead of an immediate reference to the structure of an institution, which is often a formalist argument over procedures, or to the claims of a given social group, which assumes a certain figure of agency that I would like to keep in suspense, the notion of a public sphere suggests an arena of exchange, like the ancient Greek agora or the colonial New England town hall."

It is an exchange understood in terms of an ongoing public conversation, or informed debate by citizens we can add. Or as Poster puts it, the public sphere is the place citizens interact to form opinions in relation to which public policy must be attuned. In the language of the republican tradition it is a space in which citizens deliberate about their common affairs.

The electronically mediated communications associated with the Internet mean that the face-to-face talk gives way to new forms of electronically mediated discourse. Poster points out that there is a history of electronic forms of interaction--he mentions the centralized top-down, information machines (radio and television) and their role in mediating politics. He says that the difference that is introduced by the networked media of the Internet is that:

"...it is a technology that puts cultural acts, symbolizations in all forms, in the hands of all participants; it radically decentralizes the positions of speech, publishing, filmmaking, radio and television broadcasting, in short the apparatuses of cultural production."

And it also allows for, and institutes, a communicative practice of self-constitution. This change in the way identities are structured discloses a space of a postmodern culture.

So what of the question posed earlier: is there a new politics on the Internet? Poster suggests that there is, and that it arises from the way that:

"The Internet seems to discourage the endowment of individuals with inflated status. ...If scholarly authority is challenged and reformed by the location and dissemination of texts on the Internet, it is possible that political authorities will be subject to a similar fate."

If this is so, then it represents a rupture with the old politics of the active expert addressing a passive audience and which only grants the space for the audience to ask a few questions at the end of the speech.

July 10, 2005

towards digital democracy

This post over at public opinion raises the issues of digital democracy. It argues for the need to revive and foster the political conversation in this country. A good way to do this is with a festival of ideas, as this provides a platform for people to express interesting, thoughtful ideas on topical issues. But we need to think through the relationship between a festival of ideas and democracy.

The public opinion post contextualized the Adelaide festival in the way that newspapers, radio, television and government spin constitute the informational framework of our lives, and still determine our reception of our ideas on topical issues and the way we put forward competing solutions. Public opinion suggested that the new media of the internet can, and should, provide a pathway out of the historical failure of the mass media to provide a forum for informed public debate by citizens concerned about their country.

Public opinion then criticised festival for failing to make this move to become a part of a digital world. I'm going to give some reasons here for why we need to make the move. It builds on earlier posts here and here

The Internet is new media, not just because of the technology. Though many see the Internet as a place to use words and text, others, informed by television, see it as a world of images and pictures. Public opinion assumed that the new technologies could be deployed to improve democracy, enhance civic discourse, and help the spread of a democratic political culture in oppposition to the commercial use of the internet.

In Australia democracy is representative democracy, what can be called 'weak democracy', as citizenship is limited to voting. Thsi has the following consequences: ordinary citizens can feel privatized and marginalized; the voter votes once every three years and then goes home and watches political events on the news, waits till the next election. Inbetween elections he or she lives privately as a consumer or a client letting her elected representatives do the governing. Often we have party elites and powerful leaders manipulating issues to win over impassioned, but disengaged, subjects, and gain populist approval for their hegemony.

The Adelaide Festival of Ideas introduces the active citizen who are engaged in the discussion of ideas, thereby adding to the idea of active citizens in their neighborhoods, towns, schools and churches. This presupposes social capital and trust in civil society, which is quite different from the social cohesion desired by representative-style liberal governments. The ethos of the festival--informed debate, challenging ideas, trying to shape government decisions--points to participatory democracy. But that is what we don't have in Australia.

One advantage of a Festival of Ideas embracing a digital world is its speed. Computer communication permits instant communication. This does not mean instant thinking; it does mean using the speed to post the festival speeches on a website to enable democratic deliberation. We e-citizens can read then the material at our lesiure, treat the ideas with patience and consideration. We can download them, mull over them, sift them, reconsider them, use them to question our own thinking.

That kind of critical filtering enables us to avoid the instant thinking and chatter in the form of the venting of our unfiltered prejudice and unthought opinions; and so it allow us to develop our civic and political judgement. This provides a space to avoid the mass media's relationship to democracy caused by the media's inclination to reductive simplicity, binary dualisms of left and right. It also allows us the space to explore the complexities and possibilities of the common ground between two polar alternatives.

It is often argued that a digital world has a tendency to divide,isolate and atomize people because of the necessary solitude of the computer terminal. We sit alone in front of keyboards and screens and relate to the world only virtually, our bodies in suspension, whilst we surf the net. Surfing alone leads to the privatization of politics.

This argument fails to take into account the blogging publishing platform with its public posts, comments, linkages, discussion and common deliberation. This provides a forum where those with something to say are obliged to face public scrutiny of their prejudices and publicly defend their views. So we don't just have the solitude or hyper-individualism of the virtual interface.

Benjamin Barber acknowledges the existence of the virtual communities that have been created on the Internet, but argues that they:

"...are narrow communities of interest,in effect, special interest groups comprised by people who share commonhobbies or similar identities or identical political views. Or they are a continuation of communities forged in real time and space. It's one thing to use the net to reinforce an extant community, quite another to create acommunity from pixels alone. And often, communities that use the web to spread their nets do so in the name of resistance and terror-- radical fundamentalist Christians and Islamic Jihad (not to speak of the Neo-Nazi movement)---have all used the internet to forge something like a trans-national political community. Ironically, almost all conference addressing the potential of the newcyber-technology meet in real time and space--their modus operandi standing as a living reproof to the cyber-communitarian theories they celebrate."

But bloggers do create a virtual community from their posts in spite of the partisan nature of political discourse. Barber has another objection:

"It is hard enough to determine whether cyber-community is feasible; even if we assume it is, this leaves open the question of whether democracy is likely to benefit. Representative democracy, founded on the pluralism of interests and groups and rooted in individualism and rights theory, puts little stock in communities to begin with, and its advocates are unlikely to feel benefited by whatever good deeds the new technology can perform on behalf of community. Strong democrats, on the other hand, may feel that the technologyâs ultimate benefit to participation will rest entirely on its capacity to contribute to the building of the kinds of community on which spirited participation and social capital depend."

This ignores the value of the online public discussion of ideas, the debate that takes place and the deepening understanding that comes from this conversation. The publishing technology provides micro but interlinked forums for citizens to participate in a conversation that takes us beyond asking a few questions at the end of a well presented talk by an expert in a festival of ideas.

July 08, 2005

a situation of emergency requires that ...

I've been listening to the G8 leaders and the conservative commentary on the London bombings. What I'm hearing is a particular kind of discourse that is buried within the chatter about terrorism and the rally around the flag patriotism.

The discourse says that the Islamic terrorists threaten the destruction of democracy itself, with all the values that democracy embodies and protects. In order to combat this threat effectively, democracies need to do acts that are evil in themselves but constitute a lesser evil than that posed by terrorism.

Another strand of the discourse is that we are caught up in a war on terror. The actions of Al-Qaeda are those of terrorism; terrorism cannot be countered by political means; it can only be met by war. And war entails the use of coercion, force, and violence.

Another strand is that we have to do all that is necessary to ensure the security of the (American, or Austrlaian, or British etc) people. So it is necessary that democracy, with its rights and liberties, may require an abrogation of at least some of its rights and liberties, at least for some persons and for a limited time.

It's a situation of emergency that makes it right to do this in the service of good of the civilised freedom loving peoples.

That is the conservative discourse I've been hearing in the wall to wall media commentary around the London Bombings. It makes me uneasy. But I'm not sure how to tackle it.

What is easy to say is that the state of emergency (or exception) has become the normal:--that is the insight of some of the work of Giorgio Agamben.

But I'm not sure how to deal with the ethics of this. On the one hand we have those saying that it is necessary constraining liberty in democracies to deal with threat of evil. On the other hand, we have libertarians talking in terms of the erosion of basic human rights by the national security state.

May 15, 2005

renewing social democracy?

These are conservative times we live in, as we learn to come to grips with the impact of living in a global economy, the effects of the culture wars, and the decay of liberalism. These are big changes working themselves out behind our backs and they are transforming the political landscape.

In Australia, you can see the conservatism of the times illustrated by the difficulties the Australian Labor Party (ALP) is encountering in regaining the Treasury benches. David Burchell has an op. ed. in Saturday's Australian Financial Review (subscription required) about the decline in the ALP's percentage of the primary vote. Burchill says:

"From the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, Labor's percentage share of the primary vote hovered around the mid-40s. But in the 1996 election it dipped below 40 per cvent and, aside from a brief rally in 1998, has been falling ever since. It's now heading into the mid-30s. This is territory modern Labor has never occupied before. If the trend continues, Labor could cease to be a viable alternative government."

It is not just the ALP vote. The Labor electoral brand is also in trouble as a decreasing number of Australians say that the ALP best represents their views on issues other than the core ones of health, education and enviornment. Burchill says:

'In 2001 and 2004 alike, a mere 27 per cent of respondents identified with Labor as "best representing their views". In other words, little more than quarter of the electorate identifies with what they think of as Labor values. In contrast, almost 44 per cent of respondents now believe that one or other of the coalition parties best represents their views. You could say the ALP is undergoing a crisis of relevance.'

Burchill says the ALP is primarily seen as a big-hearted party of social assistance but little else, whilst its stress on infrastructure rebuilding and skills and training is a slender platform for renewal.

Where to for renewal?

Burchill says that:

"Labor clearly needs to give voters positive reasons to vote for it. Purely defensive commitments to the survival of quality public schooling and public health are not enough---nor is a largely "me-too" approach to economic policy."

The ALP does appear to be locked into a defence of the old welfare state even though Mark Latham, its previous leader, tried to break new ground with his Third Way. Burchill makes some suggestions to what is needed:

"To generate a sense of relevance, Labor needs not just a defence-of-public schooling policy but innovative strategies for quality schooling. It needs not just a policy on hospitals and pharmaceuticals but a general strategy on health improvement and "wellness."'It needs to find creative approaches to welfare and employment that encourage independence and self-reliance, rather than simply reinforcing a now descredited and unpopular culture of welfare dependence."

I reckon that is the right pathway and one that the ALP had started to walk along.

April 19, 2005

media, democracy, postmodernism, New Right

I'm reading the last chapter of Catherine Lumby's Gotcha: Life in a Tabloid World. The chapter is entitled 'Media Culpa--democracy and the postmodern public sphere.' Tabloids promote democracy is her argument and she spells it out by criticizing a popular conception of the public sphere:

"Many critics claim that that the meaning of publis life and discourse has become so deracinated that it's now meaningless to speak of a vital public life at all...The well spring of democracy, the popular story goes, is an informed and critical citizenry, and most contemporary citizens are neither ---they're the zombie spawn of late capitalism robotically feasting on distraction and spectacle."

This is the topdown modernist view of the mass media tht has its roots in the Frankfurt's School's critique of the culture industry.

Lumby has argued throughout Gotcha that this picture of politics and popular culture:

"...is a one dimensional and hopelessly nostalgic one which ignores the myriad of ways in which the growth of the mass media has actually increased the diversty of voices, ideas and issues which make up public debate and the political arena."

The mass media is no longer the culture industry.Adorno and co have been flicked into the dustbin of history. We now study popular culture, resistance and identity politics.

Lumby then asks: 'how do we make democracy work in a world where diverse media forms compete for diverse publics?' She says that having a public conversation today means actively listening to what people are saying, regardless of how they're the saying it, where they're saying it and why. She adds:

"The top-down model of public discourse, so dear to the conventional left and right, no longer holds. We live in a world which is swaddled by communicaiton media, by films, books, magazines, radio programs, global cable TV, the Internet and video ...... Confronting this new public sphere means grasping the fundamental changes the mass media has wrought in the way we conceive of politics and culture."

Granted. What then?

Lumby says that in this postmodern world we have to rethink the old modernist dualism and assumptions about high and low, private and public, media and life etc given the diveristy of media and the plurality of new voices and groups. The media is become a vast collage of jostling diverse viewpoints, identities and genres; a sphere that is saturated with politics and which requires us to negotiate the different viewpoints and ways of speaking.

That's Lumby's argument. It is basically one about new media forms broadening and radicalising democracy.

It sort of finishes before it gets started. But this kind of postmodern argument has meant that only a handful of diehard Left intellectuals still rave against the culture industry today. The culture industry has been redefined as a respectable academic discipline, "popular culture", and it has long since ceased to be considered the opiate of the masses. It is now a legitimate terrain of contestation that provides scores of emancipatory possibilities.

What if we put the media forms to oneside and focus on democracy.

What suprises me is how hostile Lumby is to the New Right--which is symbolized by the one nation conservatism of Pauline Hanson. The New Right is seen as sinister, as being beyond the liberal pale. It is deeply racist underneath the new concept of "ethnicity".

No attempt is made to understand the undercurrent populist undercurrent that is gestures towards local autonomy, fiscal austerity and participatory forms of democracy.There is no analysis of the New Right's version of the theory of New Class domination and ideology (of political correctness)its critique of liberalism, and the violent populist rejection of liberalism's abstract universalism in favour of concrete particularity.For Lumby the New Right is really the Old Right.

A key flaw with Lumby's postmodernism is that her cultural media politics in favour of increased decomcracy is not connected to federalism. How is it possible to have radical (or direct, participatory or plebiscitary) democracy, without at the same time advocating a rigorous federal system guaranteeing the autonomy of small constituting states and the differences of regional communities?

Without federalism we are left with the centralized nation-state: the interventionist, liberal welfare state and the liberal conception of community as a bunch of abstract individuals coming together on the basis of accidental cultural identity traits.

What happens when you introduce the core categories, such as self-determination, radical democracy and federalism, into the mix? Who then are the real enemies? Who then is the opposition?

March 06, 2005

I'm on the road to Canberra. I'll post on Derrida and democracy here when I can, either later tonight or early tomorrow morning.

February 22, 2005

media mangement in liberal democracy

Over at Foucauldian Reflections Ali says that:

"Questioning and permanent questioning is the most important facet of Foucauldian politics. Those who are ruled are entitled to ask how they are being ruled, what are the implications of particular policies for their freedom, well being etc."

In the light of those remarks have a read of Mark Danner's response to Hacker and Cohen's replies to his earlier article How Bush Really Won in The New York Review of Books. It offers an insight into how the media was managed by the Republican campaign team in a presidential campaign. Danner says:

"As so often in journalism, the source offered the reporter access and the scoop; in exchange, the reporter in effect granted the source---in this case, the Bush strategistâthe power to shape the storyline. The reporter thus publishes a supposed "inside story" about "scrambling" within the campaign that is in effect a kind of "false bottom" constructed by the campaign itself and intended to "fan the flames" of what is in fact a largely bogus story."

The example mentioned is controversy over the Bush campaign's first television ads, which offered a glimpse of a dead fireman being carried out of the World Trade Center site. In the article the New York Times reporters revealed that the campaign was "scrambling to counter criticism that his first television commercials crassly politicized the tragedy of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks."

Danner adds that:

"The Bush campaign's "shocking stumble" was, in Daniel Boorstin's term, a "pseudo-event"; indeed, our political campaigns are built largely of such pseudo-events and rely fundamentally on the press and the commentariat to play their necessary part in constructing them and conveying them to the public."

It is also an insight how the media is managed by governments in power so they stay in power. The source offers the journalist access and the scoop and the journalist becomes part of the political campaign.

If we come back to Ali's account of Foucault's understanding of questioning, we find Foucault arguing that he does not question modern institutions and practices because he has some definitive alternative. Foucault questions our political institutions and practices including the state because he thinks we are entitled to ask questions about things that affect our freedom from those who rule us in the name of freedom.

Foucault makes a distinction that is very useful in terms of the media management by governments. He distinquishes between the free speech of those who govern and the free speech of those who are governed. He says that those who are governed are entitled, and they can and must question those who govern them. We can question what those who govern do, of the meaning of their actions, of the decisions they have taken; and we can do so in the name of knowledge, the experience we have by virtue of our being citizens.

February 15, 2005

Foucault and deliberative democracy

Many deliberative democrats would regard the institutions of the liberal state--its constitutional assemblies, legislatures, courts, public hearings--as the most significant venues for deliberation.

The Foucauldian critique of deliberative democracy would highlight the disciplinary function of democracy and its discourse.

The discourse of liberal democracy has its shared set of assumptions and capabilities, which enable its adherents to assemble bits of information about politics into a coherent whole, or organize them around coherent narratives. The discourse of liberal democracy is a hegemonic discourse rather than a partial one.

Focauldians, such as Barry Hindess, would argue that participation in Senate inquiries requires disciplined attendance, putting aside personal convictions, a degree of self-restraint, an ability to talk reasonably. This disciplinary self-control constructs our identities and comportment as willing participants in, and supporters of, liberal democracy.

That has to be conceded. The rules of the game in a Senate inquiry such as this one require the particpants to conduct themselves and to speak in a certain way. The form of communication is restrictive as it is required to be dispassionate, reasoned and logical. It is much more restrictive than this kind of public inquiry, in the public sphere of civil society, which would allow different forms of communication, such as testimony, rhetoric and storytelling. And we have to acknowleddge that some citizens are better than others at articulating their arguments in rational reasonable terms required in a Senate inquiry.

But that does not mean that citzens participating in the Senate's inquiry into different cancer treatments adopt a resigned acceptance of the status quo.

Participation in the proposed cancer inquiry by the Senate requires a citizen to work within the formal institutions of liberal democracy. This is a problem solving context with an emphasis on practical outcomes, as the state is still the political entity for making enforceable collective decisons in response to social problems. The senate inquiry allows citizens the space to question the bio-medical discourse about cancer, and to put a case that some allied health treatments of cancer are worthwhile. It provides a space for citizens to introduce the counter discourse of social medicine.

Does this not allow non oppressive moments?

Secondly, the setting up of the inquiry by Senator Cook was premised on the recognition of difference and the assumption that deliberation is premised on difference. As Senator Cook said:

The health debate is understandably dominated by doctors, heath-care professionals, health bureaucrats and academics, all with the apparent needs of the patient at heart but with transparent self-interests of their own. If this inquiry can stand in the shoes of patients and unambiguously take their point of view, it will be a breath of fresh air.

Not all parties to the disspute about the efficacy of the biomedical and allied health cancer treatments see themselves in competition and are concerned to win the win the argument. Some will operate in terms of this kind of strategic instrumental rationality (the AMA?) but others will operates in terms of dialogue that seeks some form of reasoned agreement though not necessarily a consensus. Agonistic difference is an aspect of the political and so we have deliberation across political difference.

What we will seen in the Senate inquiry is a contestation of discourses--a biomedical one and allied health one-- one that goes beyond the undemocratic contestation controlled by public relations experts, spin doctors and demagogues. And it may well represent a discursive shift in the way we understand cancer.

January 06, 2005

science & democracy

The politics of science. I can see the shift away from a realist metaphysics, namely:

"...the metaphysical universe of modernity...[that is]...the concept of nature as an objective entity that obeys its own laws and scientists who claim a privileged authority to represent the facts of this external realm and to interpret their implications for our lives. [This gives us] a world in which facts and values, reality and morality, science and politics, and causal necessity and freedom are seen...as dichotomous."

Latour rejects this realist philosophy of science for a more constructivist one. Well you could say that capitalism requires the subjugation of the entire objective world, which includes nature, to ensure its production. Nature must be made to appear under the instrumental control of the capitalist through the use of science and technology.

And there is a big literature on technocracy: on the way that technology and science could bring about a utopia, a society of harmony, security, abundance, and leisure; in order for these ideals to be realized, society would have to conform to the needs of the machine; with this transformation of society and its superstructure needing to be supervised by an elite group of scientists and engineers. Technocracy is a threat to democracy.

I presume this technocratic figure of modernity is what Latour is arguing against.

But I cannot see the new connection between science and democracy, other than a constructivist philosophy of science being more respectful of the multitude of diverse viewpoints, more egalitarian and more deliberative, and its denizens are ready to resolve conflicts through compromise rather than by appealing to unchallengeable knowledge or final truths.There seems to be nothing about an ethically informed and politically engaged science.

Yet technocracy has returned in the new guise of pro-genetic engineering, that defends progress as a good thing, and tells us to trust institutional science to make the right decisions.

That trust should be questioned given the philosophical background of technicism behind genetic engineering. Egbert Schuurman says:

"Technicism reflects a fundamental attitude which seeks to control reality, to resolve all problems with the use of scientific-technological methods and tools. Technicism entails the pretense of human autonomy to control the whole of reality. Human mastery seeks victory over the future. Humans are to have everything their way. We want to solve all problems, including the new problems caused by technicism; and to guarantee, whenever possible, material progress. Technicism obeys two fundamental norms, as if they are the two main commandments: technical perfection (or effectiveness) and efficiency."

That implies that it cannot make ethical judgements.The manner in which, and the means by which the ends of human mastery are achieved through scientific-technological control are not put into question.Nor are the ends that sanction the instrumental means of scientific-technological control.

December 18, 2004

democracy on the ropes

A quote from Justice Tony Fitzgerald's speech launching Margo Kingston's book, 'Not happy John! Defending our democracy', at Glebebooks in Sydney on June 22:

"My brief remarks will be directed to the damage that mainstream politicians generally are doing to our democracy...Mainstream political parties routinely shirk their duty of maintaining democracy in Australia.This is nowhere more obvious than in what passes for political debate, in which it is regarded as not only legitimate but clever to mislead. Although effective democracy depends on the participation of informed citizens, modern political discourse is corrupted by pervasive deception. It is a measure of the deep cynicism in our party political system that many of the political class deride those who support the evolution of Australia as a fair, tolerant, compassionate society and a good world citizen as an un-Australian, bleeding-heart elite, and that the current government inaccurately describes itself as conservative and liberal.

It is neither.

It exhibits a radical disdain for both liberal thought and fundamental institutions and conventions. No institution is beyond stacking and no convention restrains the blatant advancement of ideology. The tit-for-tat attitude each side adopts means that the position will probably change little when the opposition gains power at some future time. A decline in standards will continue if we permit it....In order to perform our democratic function, we need, and are entitled to, the truth. Nothing is more important to the functioning of democracy than informed discussion and debate. Yet a universal aim of the power-hungry is to stifle dissent. Most of us are easily silenced, through a sense of futility if not personal concern."

There lies the argument for deliberative democracy.

What then is the opposing view?

The opposing view ---the political consensus of the two major parties---is that economic growth comes first democracy second because economic growth creates the pre-conditions for democracy. Economic growth requires strong technocratic governance.

Now you can quite easily argue the other way. Strong economic growth has depended on a well functioning democracy and constitutional stability. What would happen to the economy if we decided our political conflicts through civil war? Australia could not have emerged as a succesful capitalist economy without a stable constitutional base, and a functioning democracy that provides for democratically elected federal and state parliaments.

Tony Fitzgerald's words, " our democracy", "if we permit it", "perform our democratic function, we need, and are entitled to the truth", [m]ost of us are easily silenced', imply us Australians speaking as citizens. Yet the word is never mentioned by Fitzgerald, even though we commonly understand citizenship to be relevant to our understanding of democracy. Is not freedom of political communication and discussion a necessary implicvation of of the Constitution's doctrine of representative democracy?

The question of citizenship is fundamental to looking at the relationship between the individual and the State. How do we determine the rights that flow from citizenship?

Is not the centrality of citizenship is the right to participate in, or to be consulted in government. Citizenship is about democratic participation in government. Citizens are those who have the right to vote. Citizens have the right to participate in, and influence our democratic system.

Does not the development of implied rights in the Australian Constitution also raise the question of whose rights? If you have the right to vote, then do you have the right to rely on the Constitutional protection of free speech in trying to invalidate a law. Do non-citizens have the protection of implied constitutional rights?

Key questions. Yet silence from Fitzgerald.

Has our political language decayed that much that we no longer talk about citizenship? Greg Craven's Conversations with the Constitution is strong on federalism and constitional order but does not explore the relationship of citzenship to the Constitution. And though the High Court is the arch of federalism it has has little to say about citizenship. Neither Craven nor the High Court seem much concerned that the Constitution still doesn't refer to citizenship.

Let me conclude with an insight from an early text by Habermas. In his 1962 work The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, Habermas argued that the competitive pressures of a free market economy eventually require state intervention and regulation, which in turn produces increased competition and still more regulation. Finally the state becomes a major player in the economic arena and is faced with what he called a "legitimation crisis" -- a set of normative contradictions -- such as the conflict between serving special interests and advancing the common good. A vibrant public sphere is the only safeguard against such a crisis, Habermas insisted. Some form of public discourse about common affairs (dialogue that arises naturally among citizens, rather than the sort orchestrated by the state), as well as an arena in which it can happen, was therefore necessary, he said.

December 17, 2004

political deliberation: looking back & forward

Parliamentary sovereignty means executive dominance after June 30 2005.

If deliberative democracy is to flourish in the new political situation of executive dominance and parliamentary sovereignty, then we citizens require more than the standard constitutional checks and balances. As Margo Kingston points out, we are lose a lot when the control of the Senate passes to the Conservatives after June 2005.

Important issues for deliberative democracy are at stake here. As Ali Rizvi says in his post, 'Towards Theorising Postmodern Activism,' at Foucauldian Reflections:

"One of the main functions of capitalist governance is to normalise the ideas, to neutralise them, take the sting out of them etc. through placing them within the discourse, and then constantly multiplying the discourse rather than repress them through inhibiting the discourse. Repression is not a chosen strategy because it is not effective in the long run among other things." (See papers, work in progress, notes etc. if link does not work).

To counter this we citizens will need a variety of spaces for us to express our views and to engage in political debate on public issues. A lot of work will be required from liberals and radicals to contest the spin and normalizing of what Margo calls an alliance of Big Government, Big Media and Big Industry.

These spaces for genuine political deliberation in a liberal polity by citizens have been few and far between in the past, as indicated by this passage from Tom Fitzgerald's last Nation editorial, when he passed the baton to Nation Review in July 1972:

"The liberal and radical strains in Australian intellectual life, though substantial in number, are always struggling to have a vehicle of communication whatever the reasons for the difficulties they are persistent and liberals and radicals, without sinking their differences, must love one another or die as an articulate force in this country."

Nation Review eventually expired, sometime in the late 1970s I think.

This lack of public space to engage in political debate means that our oppositional discourses (ie., the shared means we have of making sense of the world embedded in language) become impoverished. Often the assumptions, judgements, contentions, and dispositions lie unquestioned by others, and we become dogmatic and closed in our thinking. We cannot afford to allow that to happen over the next six years.

We need to create new spaces.

Margo Kingston's recent book, Not Happy, John! indicates that she is alive to this, and has been thinking about it off and on for a while. (See my previous posts here and here. ) She argues that the Liberal Party under John Howard has become a party of social conservatism and market fundamentalism, and more closely aligned with the conservative English Tories and American Republicans, than any genuine (social?) liberal party.

Margo explicitly addresses the renewal democracy in her last chapter of Not Happy, John! Entitled, 'Democrazy: Ten Ideas for Change', it starts from this quote by 'Gara LaMarche at the Open Society Institute in the US. He says that progressives:

"...have been in the posture of criticism for so long, have had to spend so much time fending off attacks on hard won gains, and on values and institutions we hold dear, that we have virtually lost the capacity for critical imagination. We can't see the forest we would like to dwell in because we are trying to protect tree after tree from the buzz saw."

I've suggested that 'the forest we would like to dwell in' is best described as deliberative democracy. Maybe, just maybe, it is liberalism that depletes our democratic political imagination?

I would argue that constitutional liberalism is thin on creating the diverse spaces that would enable debate and dialogue, as the institutions of the state have been their main focus of political deliberation. They focus on the House of Representatives, the Senate, the judiciary etc. Thus Carmen Lawrence's focus is on strengthing the parliamentary institutions so as to empower parliament against the dominant executive. Lawrence suggests:

"* establishing joint Estimates and Legislation Committees with power to question public servants and Ministers from either House, take submissions and commission independent research;

* giving Parliamentary Committees the power to put up legislation arising from their inquiries - especially if the government has refused to respond to its recommendations;

* allowing private bills with the backing of a set percentage of voters to be brought on for debate by a sponsoring MP;

* commissioning citizens' juries or deliberative polls on contentious and complex policy matters getting together cross-sections of ordinary Australia to hear the arguments and discuss the merits of issues as wide-ranging as water conservation and free trade agreements;

* inviting expert and community representatives to address the chamber in session and engage in debate with members; and

* strengthening freedom of information legislation."

Good ideas. But that kind of reform of Parliament is out of the question for many a long year. Remember the radical centre has been wipped out. The Greens? Not until they obtain the balance of power in the Senate. That is up to a decade away.

Carmen's proposals suggest a benign inclusion into the institutions of the state. The ACF is an example of this inclusion through its linkages to the ALP. As conservatives traditionally act to repel destablizing threats to the established order, so they will be wary of political inclusion. We need to look elsewhere. To active citizenship.

So what do Margo and her social liberal colleagues suggest on how to address the above problem? Do they shift beyond the institutions of the state to civil society? Do they start developing the idea of an oppositional civil society?

The suggestion in this post suggests a new website where journalists and Australian citizens can trust each other and work together. This is what Antony Lowenstein calls internet activism, which is idea 8 in 'Democrazy: Ten Ideas for Change'. Presumably, this is going to something along the lines of the US sites that Antony mentions, such as MoveOn.Org, and Prwatch.org and Adbusters.org

It is at this point that we need to introduce some theory by returning to Ali Rizvi's work on Foucault's understanding of the double character of freedom. Ali says:

"The apparent paradox of capitalism is that in order to increase the utility and productive capacity of individuals and populations it requires to keep expanding the ambit of freedom and diversity, but in order to make individuals and populations docile and hence governable and manageable, it needs to limit this diversity by setting limits so that it remains manageable. ........Capitalism resolves the dilemma through realising the double role freedom can play. Freedom is central for the functioning of a capitalist system not only as the precondition for enhancing utility and diversity, but for its double role as the precondition of enhancing diversity and imposing singularity on multiplicity."

It is here that Foucault makes an important point. On Ali's interpretation:

"Foucaults claim is that in capitalism the governance of diversity is maintained through freedom itself and not (primarily) through repression. Capitalisms interests are not fulfilled by curbing and limitations per se. ... Foucault defines "government as the structure (ing) of the possible field of action of others" ,....The Capitalist logic is based on a realisation that freedom is the essential element of government (management) in the sense that capitalism recognises the double character of freedom. To desire freedom is not only to expand the arena of choice (diversity) but it is also to make oneself governable (manageable)."

The net activism being created by Margo is situated itself within the double character of freedom and government rationality.

December 11, 2004

Hayek: constitutional liberalism

The basis for legitimacy says Hayek in a constitutional system is the existence of a system of laws that cannot be easily changed. The basis of legitimacy is the rule of law, not popular sovereignty.

A quote:

"The fundamental distinction between a constitution and ordinary laws is similar to that between laws in general and their application by the courts to a particular case: as in deciding concrete cases the judge is bound by general rules, so the legislature in making particular laws is bound by the more general principles of the constitution. The justification for these distinctions is also similar in both cases: as a judicial decision is regarded as just only if it is in conformity with a general law, so particular laws are regarded as just only if they conform to more general principles. And as we want to prevent the judge from infringing the law for some particular reason, so we also want to prevent the legislature from infringing certain general principles for the sake of temporary and immediate aims." F.A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty

Does that mean the people cannot change the liberal constitution through a referendum?

I raise the question naively because there is a tension betwen the idea of liberal constitutionalism ( that the powers of government should be exercised within strict limits) and democracy (the will of the people is paramount). Democracy represents a threat to the rule of law.

Update

For Hayek the organization of society is already given, as the market order has evolved spontaneously.The institutions which define the market order and protect liberty and progress are in existence. The rule of law as a set of general rules is constitutive of the market order and has emerged and evolved with it.

So the task of politics is to protect the sphere of liberty from encroachment. Moving beyond this spells disaster and leads to the dark night of totalitarianism.

December 09, 2004

from liberal to deliberative democracy

In the last chapter of her recent Not Happy, John! book, 'Democracy: Ten Ideas for Change', Margo Kingston says that the book's central premise is:

"...that just about every citizen, whatever, their political colouring, can unite on the need for an honest, open, fair, and representative democracy. If we get that then we all will have a chance to have a say, and the representatives of all of us have a chance to debate and decide the policies our society believes to be in its interests."

Democracy does need defending. And the defence of democracy has a core issue for the social liberals gathered around Margo Kingston's Webdiary.

But why representative democracy and not deliberative democracy?

We should raise this question because liberalism has been fairly silent on the issue of democracyas the emphasis is on the protection of freedom against the state (and oppressive democratic majorities) through legal means. Even John Stuart Mill, who sought to promote more expanded and informed public debate, wanted to contain that debate and prevent it from upsetting the rationality of government.

Does not contemporary liberal democracy represent a compromise between liberalism (individual rights) and democracy (popular control)? Is not liberalism premised on an account of politics as the pursuit, interaction and aggregation of private individual interests?

The competent and passionate citizens associated with Webdiary are part of the deliberation on public issues around the power structures operating the smooth constitutional surface of the liberal state in Webdiary. They are engaged in a collective discussions and decision making about Webdiary. In their critical deliberation they are transgressing liberal constitutionalism (limited government, the rule of law, and rights as a "negative" protection against arbitrary governmental interference with one's beliefs and activities). On this account individuals are left largely to their own devices in their pursuit of happiness. In these endeavors, persons rely on the principal engine of social cooperation, the free market. This is the Manchester liberalism' of the mid-nineteenth century, which has resurfaced as libertarianism, or more commonly economic rationalism.

My judgement is that the political grouping around Webdairy stands for social liberalism and the ethical state. Which means what?

Margo puts her understanding of left liberalism this way:

"Small l liberal voters have very strong views about the relationship between the citizen and the State. That was the beginning of liberalism hundreds of years ago when the struggle first started to take power away from the kings and dictators and repose it in the people. So civil liberties, civil rights and personal privacy have always been important to liberals.In a traditional sense the left side has the view that the state is good for you, and the right side has the view that it is wise to keep the State at arms length at all times and have firm structures in place at all times to keep it that way and preserve the right to challenge and have independent adjudication."

Margo tacitly claims that lefty social liberalism is a development of liberal constitutionalism and as an heir of the classical liberals. The left liberal emphasis is on freeing people through the welfare managerial state, centralized government, redistributing income, reforming the publics social attitudes and values (multiculturalism, reconciliation, the republic etc) and the managerial revolution to entrench the power of the administrative bureaucracy.

You can argue that during the twentieth century the people voted to hand over power to "public administrators" and the judges, who became the agents for practicing democracy on our behalf. Democracy was not equated with meaningful self-rule but with being socialized by administrators.

This social liberalism would be see as a deformation, not a development, of classical liberalism. That would be the argument of Frederich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises, for whom liberalism meant an economy free from the burdens of excessive government.That is the debate within liberalism that has been going on for around 30 years or more.

What Margo is arguing is that the whole notion of a centralized state that takes power from the hands of the many and place it in the hands of a detached few is anti-democratic. Hence the shift of emphasis away from liberalism to democracy, deliberation and citizenship in her Not Happy, John! Under the managerial state freedom has been seized by bureaucratic elites who now seeking control over the day-to-day affairs of individuals.

If we make the move to democracy, then we need to talk in terms of different kinds of democracy. Thus mass democracy is a government that rules in the name of the "people" but is highly centralized and operates increasingly with an ethnic-cultural core. It is a bureaucratic empire that distributes political favors and provides a minimal level of physical protection, but is no longer capable of or interested in practicing self-government. It is the democracy of the Whitlamite ALP.

Mass democracy can therefore be contrasted with deliberative democracy.

December 08, 2004

political deliberation

I am reading Margo Kingston's Not Happy, John! The core of the book is about the Howard Government's attack on Australian democracy, a defence of democracy from this attack, and some positive ideas about how we citizens can set about deepening democracy.

I did find some parts of the book naive. In Harry Heidleberg's chapter, called 'Ever More Democratic', Harry writes:

"The [media] moguls need to be reminded that in a democracy the people run the joint. We delegate our power to our political representatives but we don't do so without caveats. We know they can't be trusted with unlimited power so the Senate was designed to mitigate the power of the House of the Representatives. ....That's why a large number of people habitually vote one way in the House of Reps and another in the Senate...John Howard seeks to undermine the balance of power by detoothing the Senate, but he won't get away with it because the framers of the Constitution were smart enough to write us into the equation. Sadly for Howard we need to approve his power grab, and that will never happen."

Alas, the people voted Howard a majority in the House and Senate in 2004. He didn't have to grab power. It is was democratically given to him by the people. So we citizens become passive observers in the theatre of our democracy.

Nor did we, the people, ever run the joint, as Harry claims. The executive did within the constraints of the Senate. We, the people, had little say over the neo-liberal economic reforms of the Hawke/Keating Government in the 1980s and 1990s.

What Harry has put his finger on though is the way Margo Kingston's Webdiary "short circuited a ritualised Canberra-style debate where slogans are tossed back and forth in mindless synchronicity."

Webdiary is a part of deliberative democracy, as it is a place where public reasoning about public issues can, and does, take place. Even though Webdiary is tucked inside the big corporate media, and it is on the edges of Fairfax that the idea of political deliberation is actually being put into practice.

Harry Heidleberg gives the following account of his experience of the Webdiary process:

"The Webdiary trip taught me that ....[if] both sides [of politics] adopt a take-no-prisoners style of debate we end up with a barren sterile discussion in which the language may be strong, but the blows are as meaningful as those we see in World Championship Wrestling. Denunciations become hollow and laughable. I've learnt that meaningful blows are the ones you land against yourself or the ones where you let your guard down and give your opponent a free go."

Another word for Harry's 'process of engagement' is political deliberation. This involves reflection, participation, being amenable to changing judgements, persuasion rather than coercion, and the discussion and debate being run by citizens.

The limitations of Harry's piece is that though he sees democracy is under threat there is no reflection on deliberative democracy. He talks about core democratic values in terms of threat to media diversity, the lack of education to empower citizens and the failure of ethics in government and business. These are road blocks to a better democracy.

Democracy is seen in terms of bringing people back into democracy. And the touchstone of democracy is seen as people running the joint. But there is no reflection on the constitutional liberal understanding of democracy.

December 02, 2004

Deliberative democracy

The turn to deliberative democracy makes sense in the light of these examples of the political intimidation of public debate on matters of public importance.

Deliberative democracy highlights the way that democratic legitimacy depends on the ability or opportunity to participate in the effective deliberation on the part of those citizens subject to collective decisions. To participate in deliberation means argument, rhetoric, humor, emotion testimony, story telling or gossip. It implies an emphasis on a strong critical theory of communication, an oppositional civil society and a public sphere as sources of democratic critique and renewal. Deliberative democracy implies changing views and opinions, reasoned agreement through deliberation and and a critical voice.

This is a different conception of democracy to that of rational choice theory, which treats democracy as the strategic pursuit of goals and interests on the part of individuals and other actors. Democratic politics is seen as a contest in which individual actors compete for advantage.

I am going to put the conflict between deliberative democracy and ratinal cholice theory (politics as economics) to one side as my interest is in the way that deliberative democracy is embodied in the everyday work of the Australian or American Senate.

Saying this places me at odds with Hannah Arendt and Jurgen Habermas.They retrieve a deliberative rationality from the reasonable public discourse embodied in Aristotle's phronesis and praxis in the classical polis and rework in opposition to a hegemonic instrumental rationality in modernity.

Arendt's duality is in terms of politics (free relaxed discourse of elite individuals about matters of principle, liberty, particpation etc) and the social, which the world of inequality, crime, poverty, work .unemployment and environmental problems that is dealt with by the expert instrumental rationality of bureaucrats and administrators.

Habermas' duality is the lifeworld of social interaction where individuals construct and interpret their identity of themselves, morality, asethetics and common culture. This is constrated to the system, which is the world of state and economy ruled by instrumental rationality, cost efficiency and technical manipulation.

Arendt locates deliberation in politics not in the social, whilst Habermas locates deliberation (communicative rationality) in the lifeworld not the system and he seeks to defend the lifewold against further colonization from the system. By saying that deliberation (deliberative democracy) operates within the Senate, I am locating it within the world of instrumental rationality.

November 29, 2004

executive dominance

I have often argued for a revival of Parliament as a more significant part of the political system, often centring on the role of the Senate, or a growing of the scope for the Senate's committee input. This is a check and balance on the dominance of the executive. It is the powerful role of the Senate and the work of its committees that constitute the structural checks on the powers of Ministers and the executive.

On this account the villian is the executive, the victim is the House of Representatives and the saviour is the Senate.

Things are beginning to change as a result of the last election. It is a historic change.

The flavour of federal Parliament is that things are inwaiting for June 30th 2005, when the Coalition has control of the Senate. You can feel the muscle of executive dominance building up. The Coalition is in no hurray to rush their legislation through the next seven months. They can afford to sit and wait, as the Coalition will have a stranglehold on the Senate for around a decade.

Even if the ALP regain the House of Representatives in 2007, it will face a Coalition controlled Senate.

So how do we understand executive dominance?

My understanding is the executive dominates and controls the Parliament as a consequence of a disciplined two-party system. The party that has the majority of seats in the House of Representative can legislate and govern with few retrictions on its legislation.

The constitution appears to assume that parliament holds the executive to account. The Constitution does not codify that role or provide Parliament with accountibility mechanisms outide simple majority rule such as, independent Speaker, committees chaired by non-government members, Parliamentary confirmation of senior appointments to the public service and statutory authorities.

All we have are the conventions of reponsible government surrounding ministerial accountablity to Parliament. And I am not sure what that means anymore.

In contrast, Craven appears to argue that our constitutional system depends for its efficacy on a pervasive constitutional psychology.

In his Conversations with the Constitution Greg Craven talks about the fear of executive dominance. He says:

"This fear is the negative polarity of a profound ambivalence toward the executive. On the one hand, we are alarmed by it, and wish to limits its powers. On the other hand, we are highly depend upon it, demanding that it order our society and protect us from all ills, mortal, moral, and monetary. Simply, we expect our executive to govern us, but worry that they will take that expectation to heart."

Craven goes on to diagnose a fatal disease of executive government in our political tradition.

"There is only one fatal disease of executive governments in our tradition: an administration can survive being 'uncaring', 'unresponsive', even 'cruel' or 'dictatorial', but let a consensus form that it is 'weak' and it will succumb more quickly than a cane toad in an icebox.This is our relationship with the executive: we fear and mistrust it as the constitutional equivalent of a standover man, but if it is not adequately ruthless, we will despise it like a ruckman without punch."

This is about psychology of power exercised and not about the conventions that constrain executive dominance through responsible government. It is the psychology of strong government through executive dominance.

I would suggest that the fatal disease is that the political parties control the executive and the executive controls parliament (both the House and Senate).The major obstacle to reform is the increasing constraint of party discpline, as no political party is going to place limits on their power.

The disease is the vacuum in the heart of the Constitution about the exercise of political power by a dominant executive. The remarks by Justice Kirby in a recent speech are a counter to this. He says:

" ...in a federation, with a written constitution, the notion of unchecked legislative power, that can diminish fundamental human rights without hindrance or protection from the courts, is not likely to prevail in the long run, in the antipodes anymore than elsewhere."

For more on legal bedrocks and parliamentary sovereignty see this post.

September 01, 2004

truth in politics

Raymond Gaita's understanding of truth in politics does away with any understanding of truth as Truth (ie Absolute Truth). He has a far more prosaic understanding of truth. He says:

"Anything that counts as serious reflection will acknowledge itself to be answerable to the contrast between how things appear to us and how they are. Everyone knows that we must struggle to adjust distorting perspectives, free ourselves from prejudice, try to resist propaganda, try to resist the fashions of the times, try to overcome vanity and fears, try to resist our vulnerability to sentimentality, bathos and cliche, and so on. This is as true of narrative as it is of philosophy. These efforts are not efforts to be objective with a capital "O", they are just what it means to try to be objective in its ordinary, workaday sense of efforts "oriented towards truth".

What then is this more ordinary workaday understanding of truth?

"To seek to avoid sentimentality, for example, is to seek to avoid falsehood, as much as efforts to check on the facts are efforts to avoid falsehood. But then, one could put the point the other way about - perhaps more congenial to those who fear that talk of truth disguises an inclination to reach for a capital "T". To try to be truthful, to orient one's efforts towards truth, is nothing more than to make one's efforts answerable to those critical concepts whose applications mark our efforts to overcome vanity, seek out of the relevant facts, overcome sentimentality and so on."

We have this everyday sense operating in terms of politics around the Tampa affair or going to war with Iraq. There was a lack of honesty here. That honesty has lead to distrust between governors and governed, between politics and people. The straight talk of politicians and them being level with the people has given way to lies and spin to keep themselves in power.

Keeping themselves in power is all that matters. Everything is now bent towards ensuring this end. Even sections of the media particapte. Politics is about war and destroying the enemy. Distortion, polemics and misrepresentation have become standard operating procedure of the conservative media.

Gaita concludes his essay by saying: