October 17, 2004

Pierre Klossowski

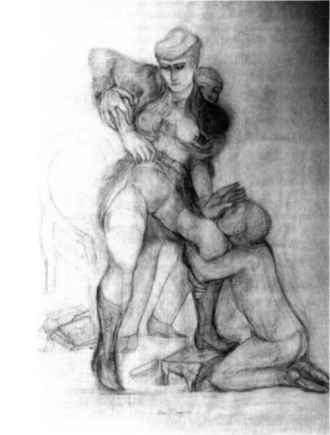

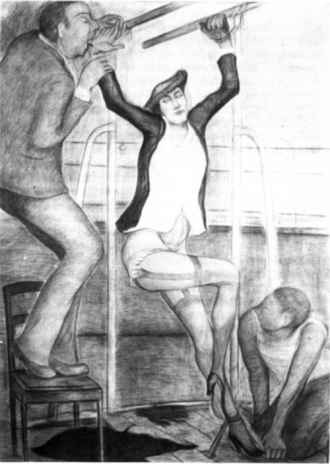

This image is by Pierre Klossowski (1905-2001). It is from his book entitled The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

This image is by Pierre Klossowski (1905-2001). It is from his book entitled The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

Klossowski played a significant role in French art, literature, and philosophy from the 1930s through the 1980s. He has a substantial corpus of erotic novels and drawings. His writings rehabilitate the Marquis de Sade as a figure of legitimate literary significance and explore the philosophical dimensions of pornography.

I can see that Klossowski was interested in the philosophical implications of Sadean pornography, rather than in violence, excess, and immorality as tools of socio-political contestation. The novels were later collected under the title The Laws of Hospitality).

The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes primarily recounts the adventures of Octave, an aging Catholic scholar who willingly gives his wife (Roberte) to all willing guests in their home so that he may experience voyeuristic pleasure and provide his nephew Antoine with a sexual education.

As with Sade, it is at first glance difficult to discern any philosophical or theological message at work in such an apparently one-dimensional narrative, particularly in light of the accompanying pencil drawings of explicit sex scenes (often orgies laced with sado-masochism) and solitary nude women displayed in various pornographic poses. It is a blueprint for male fantasy (the neurotic imagining himself as a pervert) in which the figure of the wife (Roberte) is a reproduction of Octave's obsessive image (phantasm) of his wife's body; a obsessive image expressed by the drawings.

However, I understand that Klossowski's work drew attention from influential critics such as Maurice Blanchot, Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard, and Jean Baudrillard. And I can see that there is a movement away from the humanist view of experience, in which each individual comforts him or herself with the absolute, irreducible uniqueness or originality of their feelings (however pained) – 'no one else feels as I do at this moment'.

The conservative view sees all people as figures within a pre-structured game or book of life, the 'same old song', as has it. The question of living then becomes a process of recognising – or surrendering – to this pre-givenness and fundamental non-uniqueness of individual experience, to this 'eternal return' which shapes us.

This is given a twist by Nietzsche and Klossowski we do not experience this flow of bodily desires as precious individuals that we would; rather, we do so as conglomerations of moments, echoes, gestures, postures, behaviours. These movements, these intensities, are repeated, and so in some way the same person is there, suggested with the movement of a hand, for example". This view of life is seen as a freeing from the tormenting prison of the individualist ego.

In his novel Roberte ce soir (1954).Octave, institutes an eccentric law in his household: the 'rule of hospitality' invites any guest to take advantage of his wife, Roberte. Their nephew Antoine looks on, bemused by but attracted to this odd arrangement, and to the scurrilous dialogues and couplings to which it gives rise.

In his novel Roberte ce soir (1954).Octave, institutes an eccentric law in his household: the 'rule of hospitality' invites any guest to take advantage of his wife, Roberte. Their nephew Antoine looks on, bemused by but attracted to this odd arrangement, and to the scurrilous dialogues and couplings to which it gives rise.

My judgement is that Klossowski reproduces the phallocentric gaze and power dynamic of “generic” pornography by staging the male fantasy of violent sexual domination. Within this fantasy the women, as object of male desire, is continuously tempted, inevitabily won, not so much by the impulses coming from the outside as by her own bursting, irresistible carnal desires.

A useful counter-example is the recent push by several female French filmmakers to produce sexually explicit work that subverts the power of the male gaze and addresses women’s fantasies and desires. One approaches is represented by Catherine Breillat’s Romance (1999), which uses graphic intercourse scenes as a basis for questioning the complicated relationship between physical and emotional intimacy.

Posted by Gary Sauer-Thompson at October 17, 2004 01:55 PM | TrackBack