April 14, 2005

federalism, nationality, centralism

The core of Australia's federal Constitution is that it involves the continued existence of the States as independent political entities. This federalist system of government is guaranteed not by the old doctrine of reserve powers, but by the frame of the Constitution, that is, by the federal nature of the compact.

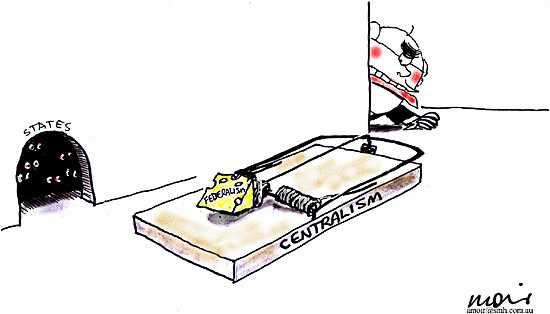

Saying that the Constitution is manifestly federalist, and full of federalist implications, is stating the obvious. But it needs to be stated, for the history of federalism in Australia in the 20th century is one of a continual decline in the authority of the States and a growth in the predominance of the Comonwealth's power.

The centralist nationalists interpret this history by saying that the significance of Federation in 1901 is the creation of one Australian nation based on sweeping away the old encumbering colonial boundaries. This emphasis on the national unity aspect of Australia as a federal nation downplays the other aspect of federalism: that Australia is a specific type of federal nation that ensures the powers of the regions (States) counterbalance the powers of the centre (Commonwealth.)

This kind of federalism means that the powers of the States are safeguarded from the Commonwealth by ensuring limits on the powers of the Commonwealth.

You can be an Australian nationalist and support this kind of federalism. We can call it a postmodern federalism to distinquish it from the 20th century duality of state rights versus centralism.

Greg Craven argues that the federalism the founders erected within the Constitution involved a carefully thought out scheme for the protection of the States.

He says that this scheme had three features:

"The first mechanism for the protection of the States was to be the conferral upon the Commonwealth of strictly limited powers. The brutally simple idea here was that even if the central government wanted to invade the spheres of the States, it would lack the legislative artillery necessary to support such a purpose. The second States--protective mechanism was indeed the Senate. If the popularly elected House of Representatives dominated by the larger States sought to have the Commonwealth strain against the limits of its legislative power, the States' House would intervene in the federalist interest. Finally, in the event that both these protective devices failed to prevent the Commonwealth from seeking to implement its designs upon the States, the High Court was to descend like a constitutional deus ex machina, and send it whimpering back within the proper bounds of its authority."

The central flaw with this scheme is the role of the High Court as the keystone of the federal arch that protected the powers of the States. As Craven observes for most of its constitutional history the Court has not only failed to protect the States, but it has been an enthusiastic collaborator of successive Commonwealth governments in the extension of central power. Posted by Gary Sauer-Thompson at April 14, 2005 12:01 AM | TrackBack