April 30, 2005

Carl Schmitt and International law #2

From what I can make out Carl Schmitt's The Nomos of the Earth is not available in English. And there appears to be little of this kind of work happening in Australia. So we have to rely on what we can find on the internet.

In his The Nomos of the Earth Schmitt represents the history of international law in three stages: the medieval respublica christiana, the jus publicum europaeum and the liberal universalism or liberal internationalism that started from the post-Versailles system.

The medieval respublica christiana was a religiously-based, homogenous order that received its validity from God as mediated by the right ecclesiastic and secular authorities claiming universal jurisdiction.

It was replaced by the territorial state as the principle of delimitation of spatial authority in Europe that realized a sharp distinction between secular and Church jurisdiction. The jus publicum europaeum that came to regulate the relationship between European states was consolidated through the great discoveries that

opened up non-European territory as a field of unlimited European land-taking and made it thus possible for the European order itself to remain stable.

The great merit of this system for Schmitt lay in the manner in which it was able to limit inter-European warfare by conceiving it as a public law status between formally equal sovereigns, by replacing the medieval notion of the justa causa belli by the formal concept of the justus hostis. This enabled enemies to be treated on an equal basis, through formal rules and without existential enmity.

With the end of the jus publicum Europaeum, the concept of war changed once again. The liberal univeralism, which buttressed the power of Western allies over their enemies, and was premised on the principle of total war, remoralised war. As a result of this remoralization of international relations aggressive war turned out to be a crime and the aggressor a criminal, who should be struggled against without any moral constraint.

April 29, 2005

social democracy and the political

The emphasis on political philosophy on this weblog arises from my realization that, in the wake of the collapse of the New Left, the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the unilinear understanding of history as "progress" and "emancipation" (ie., the inevitable march of progress), the social democratic Left, and Marxism in particular, has little to offer us in terms of political theory to analyze current political realities in a postmodern world.

Marxism has all but gone. That pretty much leaves us with a social democractic left that is committed to Enlightenment rationalism and has pretty much become a form of managerial liberalism. This Left quietly capitulated to liberal cultural hegemony, accepted the Enlightenment assumption of the system's structural soundness and infinite perfectibility and the standard Enlightenment perspective of an inevitable and irreversible progress and supported the welfare state as the only possible opposition to an otherwise triumphant market capitalism. In supporting the welfare state it a supported bureaucratic-centralist model---- statism. The state is assumed tl be the only agency able to deal with and correct the dysfunctionalities of capitalism.

Paul Piccone and Gary Ulmen state it well:

"No longer able to present themselves as the vanguard of progressive forces paving the way for a bright socialist future, they have now regrouped as part of an academic rear-guard entrusted with protecting "civil society" and liberal values against the market and other forces of darkness--a kind of quixotic kathekon seeking to prevent a recurrence of the fascist experience in a context where there has never been any such threat....this model ends up ascribing to "democratic forces" a defensive role: to prevent the alleged roll-back of the welfare state and to oppose other austerity policies under the Reagan and succeeding administrations."

Translated into Australian political realities it means a defensive stance of preventing the roll back of welfare state and opposing the austerity policies of the Howard Government.

These conservative forces are seen as retaining existing relations of privilege that stand in the way of human emancipation and are moving towards the implementation of authoritarian measures. Hence the defence of liberal institutions and fundamental freedoms from the authoritarian conservative political strategies based around "family, nation, and faith".

April 28, 2005

Carl Schmitt & International Law #1

Conservatives argue that there is a real danger arising from the growing incursion of so-called international law into the domestic business of nation states. They argue that the trajectory of international law in the past 50 years is from one that was limited to governing relations between countries, to international law now dictating relations between people within nation states. As Janet Albrechtsen says:

"Not content with asserting fundamental civil and political rights, internationalists are eager to force-feed nations on a new-fangled diet of economic, social and cultural rights....The goal is ultimately that liberal democracies built around nation states are replaced with a new form of centralised international power wielded by unelected bureaucrats and activists. Welcome to the post-democratic nation state."

Albechtsen defends the nation state in the face of those liberal cosmopolitans who have no time for the nation state. For her the ultimate touchstone is national interest of the nation state, not international law, by which she means cosmopolitan liberal humanism.

So where does that leave international law? How do we think about international law? How do we do this after the Cold War? After 9/11. Albrechtsen says little on this. She is too busy denouncing the universality of human rights of international law. So we have to look elsewhere--to Carl Schmitt.

The quote below is taken from Gary Ulmen, "Toward a New World Order: Introduction to Carl Schmitt's "The Land Appropriation of a New World", which is a chapter in Schmitt's The Nomos of the Earth. Ulmen says:

"What is most significant about the end of the Cold War is not so much that it brought about a premature closure of the 20th century or a return to the geopolitical predicament obtaining before WWI, but that it has signaled the end of the modern age--evident in the eclipse of the nation state, the search for new political forms, the explosion of new types of conflicts, and radical changes in the nature of war."

After the collapse of the Soviet empire, the US became a global system allegedly regulated by a neutral market, but under de facto US hegemony. The American government's response to the Sept. 11 attacks, defined these as (a-political) international criminal deeds and as (political) war acts. So it introduced a new concept of war and legitimated military intervention anywhere, while reserving the right to decide unilaterally which actions to take.

Australia has followed suit, only to confront the realities of international law in the Asia Pacific Rim. Australiais required to commit to the region's Treaty of Amity and Co-operation in return for a foundation seat at the new East Asia summit.

Carl Schmitt's The Nomos of the Earth is one of Schmitt's post 1945 writings on war and international order, which starts from the collapse of the Westphalian State system and the political marginalisation of Europe. It describes "the Eurocentric epoch" of world history as beginning with the discovery of America and ending with the rise of the US as a world power after 1945. The central part of The Nomos of the Earth is the chapter titled "The Land Appropriation of a New World."

Schmitt argues that the emergence of inter-State system in Europe was made possible by the land appropriation of "non-Europe". Spatial distinction between "Europe" and "non-Europe" was a necessary condition of the European sovereign State system. "Europe" means a civil state, state of law, state of society, while "non-Europe" is, consequently, a state of nature, state of war. Where social contract theorists would suppose a chronological succession between these two states (from Nature to Society, from war to peace), Schmitt sees a geographical relationship. Colonial violence in "non-Europe" is without limit. Violence in "Europe," with rule.

Australia was a part of non-Europe where colonial violence was without limit.There the brutal violence is the appropriation itself. He understands the sharing of the world is itself unavoidably destructive and with violence.This violence involves the way in which indigeneous people's land appropriation and form of life is uprooted.

Within Europe this new, state-centric system of public order there was the the transformation of the religiously-inclined just war into a purely secular notion of the formally legal war between European states. In the European era war became a regulated rivalry, a duel between formal states, conducted strictly following the procedures laid down by the jus publicum europaeum, while unlimited enmity was projected "beyond the line"--into the non-European world.27

April 27, 2005

Schmitt, Anzacs, conservatism

I continue to puzzle about the formation of conservatism that is happening around us today. It was very evident in the Anzac rhetoric, and so I want to connect it up with political philosophy to try and understand the nature of conservatism. This is philosophy apprehending is its own time in thought, if you like; one that makes a judgement that conservative ideas are having considerable repercussions throughout Australia.

The current time is one which appears as if the Left seems theoretically and politically finished, whilst the Right is experiencing an unexpected renaissance. Do these developments signal a major paradigm shift threatening the reconfiguration of post-Cold War politics? If so then how do we understand conservatism?

The core conservative category, and one we find in both Carl Schmitt and Thomas Hobbes, is the obedience/protection category. This holds that sovereignty resides where there is power to provide protection from enemies in return for obedience. A strong state applies the obedience/protection principle correctly. With Hobbes this category leads to the absolute state, whilst for Carl Schmitt it leads to the total state. For both the state is the guarantor of order and it's power ultimately rests on the executioner.

Now I want to suggest that it is Schmitt, not Hobbes, who can give us some insight into the formation of contemporary conservatism. My reason for this is that Hobbes is too individualist: the foundation of Hobbes's protection/obedience category is an over-riding concern for individual survival. The individual owes obedience to the state, as long as his own self-preservation is safeguarded by the state. That is not the way of Australian conservatism. It talks about the Anzacs defending our national way of life.

John Howard, the Australian Prime Minister, in his address at the dawn service at Gallipoli said:

"Ninety years ago, the first sons of a young nation assailed these shores. They forged a legend whose grip on us grows tighter with each passing year. Those who fought here changed the way we see our world: they strengthened our democratic temper and our questioning eye towards authority."

My suggestion is that we can use Schmitt's categories to move beyond the old left dualism of the paladins of liberal-democratic values of "liberty, equality and fraternity opposing the forces of evil embodied in "anti-democratic" and "neo-Nazi" networks that seek to legitimate their sinister projects of exclusion, violence, crime.

Schmitt's focus is the group: the over-riding concern of his protection/obedience category is the preservation of a group's political identity, a set of goals, a way of life. Since the focus is the preservation of the way of life of a group, then the loss of life of a single individual becomes acceptable. Hence we have all the Anzac sacrifice forging 'the nation' and sacrifice talk of recent days.

Schmitt's category of the political is also useful, as enmity is the relationship of a group against another. Politics can never abolish enmity, as the latter is the very essence of politics. The political is any force that brings people together as friends against other people regarded as enemies. The friend/enemy antithesis is the essence of the political, an antithesis that has always existed and is likely to persist in the future. So politics as a struggle of friends against enemies is in our history as well as our destiny.

Thus we have all the conservative talk in the clash of civilizations about the enemy, by which they mean terrorists plus those liberals and anti-American lefties who opposed the war on Iraq. The identity of the group emerges through psychological and physical confrontation with the enemy and, conversely, through the psychological and physical collaboration with friends.

Schmitt highlights the way that conservatism is opposed to, and critiques liberalism. He argues that liberalism fails to see that politics is above all a struggle to establish our identity. Liberalism does not see identity as a problem, but as a starting point, as an assumption. As identity and rights are not questioned, but assumed as given, politics for liberals becomes less important and less fundamental than, for example, economic interaction.

Because liberals do not feel that group identity is at stake, their politics is marked by never-ending discussions, procrastination, indecision, and general gossiping. Liberal politics becomes a discourse on matters of minor concern; tradeoffs and compromise are alwaysconsidered possible because what is discussed in never existential. As a result, liberal politics is never serious.

Only when identity, life and death are at stake, do we have a real concern, a real commitment, a real determination, to find solutions, a real need to take decisions. When identity is at stake, compromise and tradeoffs are inconceivable. The struggle for identity is

real and not a product of philosophical imagination; it is a struggle that takes place all the time, both at a national and international level.

The significance of the Anzacs for Australian conservatives is that it is about national identity: it was a struggle for national identity in which the youmg Australians confronted death.

Schmitt can also help us to the tectonic shift to conservatism and away from liberalism. He argues that a constitutional liberal state with its rule of law can cope with everyday politics, but not with a state of emergency. A liberal democracy, with all its checks and balances, with its divisions of powers and competences, with its complex bureaucracy and decision-making processes, can never cope adequately with the exception.

I have previously argued that today it is terrorism that is the prime exception that disrupts the regularities of everyday politics. What we have find is less the liberal state coping with the war on terrorism without renouncing its liberal and democratic principles, and more the transformation of the liberal state into a total state in the form form of the national security state?

April 26, 2005

Kim Beazley on Anzacs & strategic policy

Yesterday was Anzac Day in Australia:

I read some of the commentary in the corporate media written about the Anzacs, Gallipoli 1915 and the Anzac Legend over the weekend.

I read some of the commentary in the corporate media written about the Anzacs, Gallipoli 1915 and the Anzac Legend over the weekend.

I was doing a bit of research--as much as I could do using dial-up internet-- for my posts on Public Opinion and Junk for Code.

Most of the commentary, including that on the weblogs, was about the new generation of cosmsopolitan Australians discovering their history, expressing their feelings of national pride and reinventing Anzac Day as a national day. The Anzac legend, with its values of heroism, courage and sacrifice, lives on is the theme of the commentary.

It is acknowledged that the Diggers were reluctant heroes and that the military campaign was poorly planned by the British.

It is acknowledged that the Diggers were reluctant heroes and that the military campaign was poorly planned by the British.

The emphasis of yesterday's rhetoric was on mateship, sacrifice and national pride. Around 50,00 young Australian men died at Gallipoli. Slaughtered by all accounts.

No matter. Anzac Cove has now become a sacred site because the blood sacrifice changed the way we Australians saw the world and understood ourselves.

So why was Australia on the beaches of Gallipoli in 1915? Why celebrate a failed invasion of a distant country in which Australia had no strategic interest?

Horace Moore-Jones, The Coast North of Anzac Cove, 1915.

We should press this line of questioning, even though it makes us feel uncomfortable, because it leads to strategic policy considerations.

What was Australia doing there for heavens sake? It was on the other side of the world:

By all accounts Australia had no strategic reason to be there in the Middle East.

By all accounts Australia had no strategic reason to be there in the Middle East.

Who were we defending Australia from?

The Turks?

But they were defending their homeland were they not?

It was Australia who was invading their homeland. It was Australia making war on Turkey, a country with which we had no quarrel and no history of conflict. Why the invasion?

Did not the Turks defend their homeland from invasion with courage, tenacity and honour?

Did they not hold out against the Australian invaders and eventually repel them?

What was a Labor Government (that of Andrew Fisher) doing sending Australian volunteer troops to fight in the terrible terrain on the edge of the Midlde East?

Horace Moore-Jones, The Terrible Country Towards Suvla, 1915

Doing our duty for the British Empire is the common and conventional answer to this line of questioning. Australia simply provided the canon fodder so that the British Empire could defend its imperial interests.

Not so says Kim Beazley, leader of the ALP. In a recent address to the Lowy Institute he defended Australia's involvement on good strategic grounds. This is a historical revisionism. How plausible is it?

Before he makes his case Beazley outlines 4 strategic premises that he says guides his thinking about Australia's national security.

"The first is that I do not take Australia's security for granted. Nothing in our nature as a country - our values, our people or our institutions - guarantees that the world will do us any favours. Our future security depends on the nature of the global and regional international systems, the scale of our national resources and the skill and effectiveness of our policies.Second, Australia's future security is in the hands of no one but we Australians ourselves. Our circumstances are unique, and so are our responsibilities. Some find it easy to fall back on the idea that we can sub- contract our security to others. We cannot. It is our responsibility alone.

Third, to fulfil that responsibility Australian governments must provide realistic assessments of our national situation; active, imaginative and effective policymaking; a tough sense of priorities; a long-term view; and a true appreciation of our assets and liabilities.

And fourth, the mark of good Australian policy is not how it deals with artificial choices between regional and global engagement, but how effectively it marshals all the policy options available to meet Australia's unique interests."

These premises of strategic policyre national security are acceptable to me.

So how does Beazley deploy them in relation to Gallipoli? He does by criticizing the conventional position. Beazley says that like all legends the ANZAC story takes on an air of inevitability:

"It is impossible to imagine a world in which Australians did not go ashore that morning at Gallipoli. But there was nothing inevitable about it. They were there because of policy decisions - strategic decisions - taken by Australian political leaders."

Fair enough.

"The Gallipoli legend of today minimises these decisions. It suggests that Australians found themselves on the Turkish shore that day because their political leaders were too unimaginative, too supine, too emotionally tied to Britain to see that this was someone else's war, in which Australia had no part."

Beazley says that this is a travesty of the truth. A truer account of the strategic dimensions of the Gallipoli story deserves to be better known. He then outlines his case:

"Australians as a people thought carefully about their security in the decades before 1914. As the strategic challenge from Germany grew from the 1880's, they recognised that Britain would be less and less able to continue guaranteeing Australia's security. And they realised that as Britain started looking for allies in Europe and Asia, its interests would sometimes diverge from Australia's. We started to see ourselves, not as a mere strategic appendage of empire, but as an active partner in imperial security. As such we had our own unique interests and perspectives, and our own responsibilities."

John Quiggin takes exception to this paragraph.

I will grant that a developing independence in strategic thinking about national security can be granted. So our strategic policy was increasingly built on own unique interests perspectives and responsibilities. But I have more questions?

Does Australia's national interest coincide with imperial interest of the British Empire in 1915? Did we really act as active partners in imperial security then?

However, Beazley is quite sure about this. So how does he argue his case? He says:

"We cannot understand the decisions of 1914, and we cannot understand Gallipoli, if we do not understand that Australia had compelling, direct and distinctively Australian strategic reasons to play its part in helping to ensure that British power was not eclipsed. We needed Britain to defend us from what we saw - rather presciently as it turned out - as direct threats closer to home."

We needed Britain to defend us direct threats closer to home. Australia's compelling, direct and distinctively strategic reasons were the direct threats to our homeland.

What were these threats? None come to my mind. Australia was not threatened by China or Japan. Or did Andrew Fisher peer into the glass darkly? All that Beazley says is that Australia has global interests in 1914. So what were these global interests that ensured Australia had to invade Turkey in 1915?

Beazley does not say. We have silence other than vague estures to the future-Japan in the 1930s? This historical revisionism amounts to going along with 'great and powerful friends' to ensure their support. It is the security insurance doctrine of foreign policy.

April 21, 2005

Carl Schmitt & total state

In Four Articles 1931-1938 Carl Schmitt argues for the emergence of a total state. How relevant, or useful, is this idea to the current situation of the conservative national security state fighting the war on terrorism?

Schmitt traces the emergence of the total state in a variety of ways. He says:

"In every modern state, the distinction between state and economy emerges as the real issue of the current, direct questions of internal policy. They can no longer be answered by means of the old liberal principle of unqualified non-interference and unrestricted non-intervetion. ..In the present day state, the economic questions constitute the core of the difficulties of the internal policy, and all the more so, the more modern and industrial the state is. Internal and foreign policies are economic policies to a considerable extent, and...not just as customs and trade policy or as social policy."

This is familar to us. It is the Keynesian welfare state. But Schmittt goes further in delineating the contours of the emerging total state. The transformation in the nature of the state can also be seen in the resistance to, and clampdown on, the powerful legislative state:

"At the very moment whern the victory seemed to be fully its own, parliament, the legislative body, the vehicle and keystone of the legislative state, turned into a contradiction-ridden structure, disowning its own qualifications and premises of its victory [over the old monarchy]. Its previous position and superiority, its expansionalist drive at the expense of the government, its representation in the name of the people, all that presupposed the distinction between state and soceity did not survive the parliament's victory, at least not in that form."

Schmitt goes on to say that Parliament changes itself from:

"...a stage for unifying free debate among free representatives of the people, from a transformer of narrow party interests into a supra party will, into a stage for the pluralistic division of the organized societal powers."

The name for this tendency of overcoming the sovereignty of Parliament in Australia is executive dominance.

April 19, 2005

media, democracy, postmodernism, New Right

I'm reading the last chapter of Catherine Lumby's Gotcha: Life in a Tabloid World. The chapter is entitled 'Media Culpa--democracy and the postmodern public sphere.' Tabloids promote democracy is her argument and she spells it out by criticizing a popular conception of the public sphere:

"Many critics claim that that the meaning of publis life and discourse has become so deracinated that it's now meaningless to speak of a vital public life at all...The well spring of democracy, the popular story goes, is an informed and critical citizenry, and most contemporary citizens are neither ---they're the zombie spawn of late capitalism robotically feasting on distraction and spectacle."

This is the topdown modernist view of the mass media tht has its roots in the Frankfurt's School's critique of the culture industry.

Lumby has argued throughout Gotcha that this picture of politics and popular culture:

"...is a one dimensional and hopelessly nostalgic one which ignores the myriad of ways in which the growth of the mass media has actually increased the diversty of voices, ideas and issues which make up public debate and the political arena."

The mass media is no longer the culture industry.Adorno and co have been flicked into the dustbin of history. We now study popular culture, resistance and identity politics.

Lumby then asks: 'how do we make democracy work in a world where diverse media forms compete for diverse publics?' She says that having a public conversation today means actively listening to what people are saying, regardless of how they're the saying it, where they're saying it and why. She adds:

"The top-down model of public discourse, so dear to the conventional left and right, no longer holds. We live in a world which is swaddled by communicaiton media, by films, books, magazines, radio programs, global cable TV, the Internet and video ...... Confronting this new public sphere means grasping the fundamental changes the mass media has wrought in the way we conceive of politics and culture."

Granted. What then?

Lumby says that in this postmodern world we have to rethink the old modernist dualism and assumptions about high and low, private and public, media and life etc given the diveristy of media and the plurality of new voices and groups. The media is become a vast collage of jostling diverse viewpoints, identities and genres; a sphere that is saturated with politics and which requires us to negotiate the different viewpoints and ways of speaking.

That's Lumby's argument. It is basically one about new media forms broadening and radicalising democracy.

It sort of finishes before it gets started. But this kind of postmodern argument has meant that only a handful of diehard Left intellectuals still rave against the culture industry today. The culture industry has been redefined as a respectable academic discipline, "popular culture", and it has long since ceased to be considered the opiate of the masses. It is now a legitimate terrain of contestation that provides scores of emancipatory possibilities.

What if we put the media forms to oneside and focus on democracy.

What suprises me is how hostile Lumby is to the New Right--which is symbolized by the one nation conservatism of Pauline Hanson. The New Right is seen as sinister, as being beyond the liberal pale. It is deeply racist underneath the new concept of "ethnicity".

No attempt is made to understand the undercurrent populist undercurrent that is gestures towards local autonomy, fiscal austerity and participatory forms of democracy.There is no analysis of the New Right's version of the theory of New Class domination and ideology (of political correctness)its critique of liberalism, and the violent populist rejection of liberalism's abstract universalism in favour of concrete particularity.For Lumby the New Right is really the Old Right.

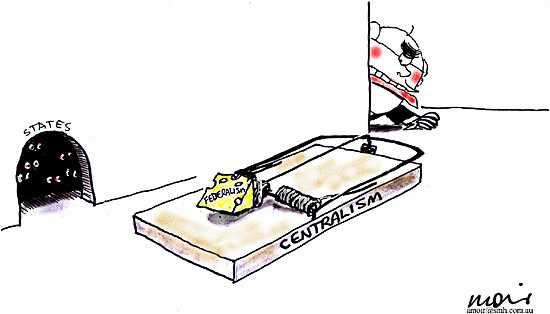

A key flaw with Lumby's postmodernism is that her cultural media politics in favour of increased decomcracy is not connected to federalism. How is it possible to have radical (or direct, participatory or plebiscitary) democracy, without at the same time advocating a rigorous federal system guaranteeing the autonomy of small constituting states and the differences of regional communities?

Without federalism we are left with the centralized nation-state: the interventionist, liberal welfare state and the liberal conception of community as a bunch of abstract individuals coming together on the basis of accidental cultural identity traits.

What happens when you introduce the core categories, such as self-determination, radical democracy and federalism, into the mix? Who then are the real enemies? Who then is the opposition?

April 16, 2005

Iraq & media management

If you have a moment this weekend do have a read of Mark Danner's article Iraq: The Real Election It separates out what we see on our television screens from what is happening on the ground with the Iraqi's.

What we see on the television is the management of the news to fit the US narrative about bringing democracy to the Middle East. Danner says:

"During the more than two years since the Iraq war began Americans have seen on their television screens its four major turning points: the fall of Baghdad, the capture of Saddam Hussein, the "transfer of authority" to the interim Allawi government, and now the Iraq elections. Each has been highly successful as an example of the management of images—the toppling of Saddam's statue, the intrusive examination of the unkempt former dictator's mouth and beard, the handing of documents of sovereignty from coalition leader L. Paul Bremer to Iraqi leader Iyad Allawi, the voters happily waving their purple fingers— and each image has powerfully affirmed the broader story of what American leaders promised citizens the Iraq war would be. They promised a war of liberation to unseat a brutal dictator, rid him of his weapons of mass destruction, and free his imprisoned people, who would respond with gratitude and friendship, allowing American troops to return very quickly home."

Now we know that this didn't actually happen. But Danner probes this further. He adds:

"With the exception of the failure to find WMDs, the images have fit so cleanly into the original narrative of the war that they could almost have been designed at the time the war was being planned. And because these images fit so closely with the story of what Americans were told the war would be, they have welcomed each of them with enthusiasm. Unfortunately, after the images faded, the events on the ground that followed refused to fit that original narrative."

Election Day held the narrative together. It gave it new life. It was the perfect symbol of liberation as it embodied the war's purpose in a single image of Iraqis waiting to express their voices in an exercise of democratic will.We in Australia were flooded with this for days on end.

How did it work on the ground?

Danner was able to talk to people as they voted. They say things differently:

'"Why are you here, I asked a young man wearing a Ray's Pool Hall shirt. "Why?" He looked surprised. "To vote." But why, why did you come? "We are a normal people, an independent people. We want to be like other people, to vote. We need security, stability—that's all." He volunteered nothing about Saddam, about the war, the Americans, the occupation; when asked he seemed reluctant, like many of his neighbors in line, to discuss them.A young woman, wearing a beautiful sea-green abeya, asked by a colleague about Saddam, grew annoyed. "No, this is not about Saddam. Forget Saddam. I am an engineer and I have no job. Neither does my husband." Then, a bit exasperated, "We want a normal country."'

Danner says that the mostly middle-class people he spoke to expressed this view again and again: the desperate need for security, for stability---for normalcy. Danner adds that:

"We needed someone to say: Thank heaven Saddam has gone, thank heaven the Americans came, thank you for giving us democracy. And no one—at least here in this voting place in Baghdad—seemed to want to say it."

There lies the gap between western media representations and everyday life in Baghdad.

April 15, 2005

a progressive ALP?

I cam across this over at the Evatt Foundation in an article by Sol Encel. Encel says that an essay on '21st Century Citizenship', published by the think tank Demos, (I cannot find the essay) identified three basic values which should characterise a progressive party in tune with contemporary realities. These are:

"· to offer a basic level of security and social fairness which equips each individual to develop and contribute to his or her full potential;· to promote and enable forms of collective action which contribute to the overall vitality and fairness of society as a whole;

· to create countervailing institutions which limit the power of the state and the market, and align the energies of capitalist wealth production with human need."

Encel defends this by arguing that a progressive ALP would argue in favour of changing the structures which perpetuate social inequality as opposed to an ALP that is managerial, and so concerned with just the better administration of society.

April 14, 2005

federalism, nationality, centralism

The core of Australia's federal Constitution is that it involves the continued existence of the States as independent political entities. This federalist system of government is guaranteed not by the old doctrine of reserve powers, but by the frame of the Constitution, that is, by the federal nature of the compact.

Saying that the Constitution is manifestly federalist, and full of federalist implications, is stating the obvious. But it needs to be stated, for the history of federalism in Australia in the 20th century is one of a continual decline in the authority of the States and a growth in the predominance of the Comonwealth's power.

The centralist nationalists interpret this history by saying that the significance of Federation in 1901 is the creation of one Australian nation based on sweeping away the old encumbering colonial boundaries. This emphasis on the national unity aspect of Australia as a federal nation downplays the other aspect of federalism: that Australia is a specific type of federal nation that ensures the powers of the regions (States) counterbalance the powers of the centre (Commonwealth.)

This kind of federalism means that the powers of the States are safeguarded from the Commonwealth by ensuring limits on the powers of the Commonwealth.

You can be an Australian nationalist and support this kind of federalism. We can call it a postmodern federalism to distinquish it from the 20th century duality of state rights versus centralism.

Greg Craven argues that the federalism the founders erected within the Constitution involved a carefully thought out scheme for the protection of the States.

He says that this scheme had three features:

"The first mechanism for the protection of the States was to be the conferral upon the Commonwealth of strictly limited powers. The brutally simple idea here was that even if the central government wanted to invade the spheres of the States, it would lack the legislative artillery necessary to support such a purpose. The second States--protective mechanism was indeed the Senate. If the popularly elected House of Representatives dominated by the larger States sought to have the Commonwealth strain against the limits of its legislative power, the States' House would intervene in the federalist interest. Finally, in the event that both these protective devices failed to prevent the Commonwealth from seeking to implement its designs upon the States, the High Court was to descend like a constitutional deus ex machina, and send it whimpering back within the proper bounds of its authority."

The central flaw with this scheme is the role of the High Court as the keystone of the federal arch that protected the powers of the States. As Craven observes for most of its constitutional history the Court has not only failed to protect the States, but it has been an enthusiastic collaborator of successive Commonwealth governments in the extension of central power.

April 12, 2005

Constitutional Interpretation #2

In an op. ed. in The Australian criticizing the emerging centralist tendencies of the Howard Government, Jeffrey Phillips, a Sydney barrister specialising in industrial relations, observed that:

"The intellectual Right in Australia has condemned the centralist tendencies of Labor and Liberal governments and has, in more recent times, condemned the use of the external affairs power enabling Canberra to regulate internal matters."

He mentions the Samuel Griffith Society, as an example of the intellectual right, then adds:

"Whether or not conservative and right-wing supporters of the federal Government are able to change its mind in relation to a single industrial relations system, there are considerable doubts as to whether a change of such radical proportions would pass scrutiny in any High Court challenge."

His reasoning is this:

"The [High] court led by Anthony Mason was clearly centralist in its approach. Whether the court led by Murray Gleeson is of a similar vein is to be determined, but it certainly looks conservative....With the profound changes in the High Court's composition since that time, any suggestion that the use of the corporations power to completely take over the industrial relations system is a fait accompli would appear to be, on its face, somewhat hopeful."

Would a conservative High Court turn its back on a 80 years of fostering centralism? Certainly the Mason Court's progressive judicial activism in the 1990s (ie., constitutional activism in cases like Australian Capital Television created an implied freedom of political communication) has become far more constrained with the Gleeson High Court.

Would a conservative High Court begin to turn its back on 80 years of fostering centralism? Would it recover the founder's conception of Australian federalism, that of the coordinate government of States and Commonwealth?

It is not certain. What is discernible is that judicial activism has been a feature of conservative as well as progressive High Courts. Was not the 1920 the decision of the Court in Engineers case in 1920 to interpret the Constitution according to a rule of literalism, the beginning an on-going process for the centralisation of Commonwealth power via judicial sponsorship?

What if a conservative High Court did so return? Say it did so in order to safeguard our liberties, from a conservative Howard Government trampling on the principle of balanced government through seriously undermining the power of the States, and compromising the Senate, as both a House of review and of federal diversity.

How would the High Court interpret the Constitution to justify a more balanced conception of federalism?

Greg Craven points out two difficulties. The first is that:

"....Australian lawyers, and especially conservative lawyers, traditionally despise theory, preferring the case-by-case logic of the common law. Indeed, until the early '90s there virtually was no constitutional theory in Australia, and anyone interested in the topic was regarded as profoundly eccentric...."

The second is the difficulty:

"...that conservatives have tended to take an extremely unsophisticated view of constitutional interpretation. If asked what they do when engaged in the process, they tend to respond that they are reading the words. If further asked what is involved in reading the words, or whether words can have more than one meaning, or whether Constitutions contain more than just words, they generally are irritated, covered with confusion or both. Yet what is required in any theoretical contest are sophisticated theoretical apologists, and these tend not to arise in large numbers on the conservative side of Australian constitutional debate."

The possibilities of constitutional interpretation are covered here.

April 11, 2005

constitutional interpretation

The framers of the Australian Constitution, unlike their US and Canadian counterparts, decided to open their Constitutional debates to the public and to have parliamentary shorthand writers take down and publish their words. The Australian framers wanted us citizens to read the text of the Constitution in the light of their debates.

Yet for a long time---most of the 20th century in fact--the High Court split the text of the Constitution from the movement towards federation, and the debates about the Constitution, from which the text of the Constitution finally emerged. The Constitution was a stand alone text.

It was in his review of La Nauze's book,The Making of the Australian Constitution, that Leslie Zines reproduced that famous piece of High Court absurdity, the argument in Strickland v Rocla Concrete Pipes Ltd in which counsel and judges debated what they would find if they looked at the Convention Debates, while all the time affirming that, of course, they were not allowed to. The extracts ended with the following exchange:

Mr Ellicott: My friend Mr Lyons did refer to the convention debates as if they might support the view for which he contended. That reference, of course, was not permissible; but all I want to say is that if they were looked at, one would find the contrary.

Menzies J: That, too, is impermissible.

Mr Ellicott: No doubt your Honours will not look at them.

This hermeneutical nonsense didn't end until the 1980s. It is nonsense because the High Court purportedly grounded its constitutional interpretation in the "intention" of the Constitution(how can a text have an intention?) and yet, until the landmark decision in Cole v Whitfield in 1988), it did not permit recourse to the actual Convention Debates of the 1890s to guide the interpretation of the constitution.

It implied a legalism in which certainty is achieved by making constitutional law seem less value-laden, more interpretation-free, and less infused with the shaping of political relations (Federal/State) than it actually is. Legalism rejects the use of external political principles or policies to interpret the Constitution, and it displaces the subjective value judgements of individual judges.

Legalism is difficult to accept since Australia has a "bare bones" Constitution where much is left unstated, presupposed, unwritten (and flexible) conventions, and where implications are to be drawn from the text of the written Constitution.

Legalism often presupposes a literal approach to intepretation is that words of the reified text even have a single "natural and ordinary" or "essential" meaning that can be discerned.

Literalism as a mode of contitutional interpretation is difficult to accept since most words have numerous potential meanings. The actual meanings they do bear in any given situation depends on the context, history and the social setting in which they are uttered. Moreover the meanings of individual words shift depending on their relation to other words to other paragraphs in the text of the Australian Constitution and the relation this text to another text(eg., The American Constittuion).

April 9, 2005

challenging Liberalism

The political life of Australia has been, and should be, portrayed as working within a hegemonic liberal consensus. Liberalism is the political theory implicit in our political practice, and it articulates the assumptions about citizenship and freedom that inform our public life.

Liberalism is rooted in its conception of freedom, and this is understood as the capacity of free subjects to choose their own values and ends. Hence all the emphasis on freedom of choice with respect to universities and compulsory unionism.

If liberal politics focuses on the capacity of individuals to form and revise their conception of the good, then the liberal state remains neutral as to the goods which individuals pursue.

So argues Michael Sandel in relation to US liberalism, but that account applies here as well, despite the utilitarian emphasis of Australian liberalism.

The liberal state does not support any one comprehensive conception of the good life but allows individuals to choose their own conceptions provided these are just. Liberalism holds that government should not affirm in law any particular vision of the good life. Instead it should provide a framework of rules (or rights) that respects persons as free and independent selves capable of choosing their own values and ends.

Now liberalism has difficulty articulating our concerns and anxiety about the erosion of community, the loss of self-government, and the impoverished conception of citizens. Conservatism addresses the erosion of community but has little to say about self-government or citizenship. The latter can be addressed by republicanism, which holds that individual freedom must be achieved through communal political activity; through deliberation on the common good and concern for public affairs.

The welfare state of the 1940s that was put in place by the Chifley government was a response to the massive unemployment and financial chaos brought on by the collapse of industry and the capitalist economic system during the 19130s Great Depression. Liberalism was found to be wanting. Left to itself, the free play of individual interest produced an inherently unstable economy with dramatic effects on the political and socio-economic lives of all citizens. One could no longer have faith in the combination of laissez-faire and survival of the fittest to provide a workable social order. Both rich and poor were devastated by the economic collapse. The depression marked a practical demonstration that laissez-faire capitalism was not a natural order as even those who were judged to be the fittest suffered during the depression.

This shift to the welfare state has generally been interpreted in terms of social liberalism. Does it have a republican moment? Can we say that the growing acceptance of the idea that the federal government had the right and the duty to intervene on behalf of the economic well-being of its citizens led to the corollary that the federal government had the obligation to protect the lives and constitutional rights of Aborigines? Does not extending citizenship to aborigines and the freedom rides of the 1960s suggest a republican interest in civic engagement, self-government, and the common good<

April 8, 2005

Leo Strauss & political philosophy #3

Strauss says that his return to antiquity is necessitated by the crisis of our time, the crisis of the West. Strauss, like Nietzsche and Heidegger, sees a crisis of nihilism at the heart of modernity. This crisis opens up the possibilty of a return to a principle forgotten or lost sight of within modernity.

Like Nietzsche and Heidegger, Strauss holds that the recovery of this lost principle involves a return to the ancients who are now able to speak to us free from the distorting effects of modern assumptions.For Strauss, the problem of modernity is not represented by phrases "the death of God" (Nietzsche) or "the forgetting of Being" (Heidegger).It is represented by relativism, by which Strauss means that for the moderns no particular way of life has inherent worth.

Relativism means the rejection of natural right. The principle to be recovered is natural right.

In contrast to Heidegger, Strauss does not turn to the pre-Socratics. He returns to Plato and Aristotle--those thinkers who Nietzsche and Heidegger argue are the architects of Western metaphysics and thus fully implicated in the presuppositions of a nihilistic modernity.

April 7, 2005

Carl Schmitt, dictatorship & the state of exception

Agamben says that the most rigorous attempt to construct a theory of the state of exception was made by Carl Schmitt in his two books Dictatorship and Political Theology. Agamben says that:

The specific contribution of Schmitt's theory is precisely to make...an articulation between state of exception and juridiucal order possible. It is a paradoxical articulation, for what must be inscribed within the law is something that is exterior to it, that is, nothing less than the suspension of the juridical order itself...."

In Dictatorship Schmitt presents the state of exception through the figure of dictatorship. He distinquishes between a commissarial dictatorship, which has the aim of defending or restoring the existing constitution; and sovereign dictatorship, which aims at creating a state of affairs in which it becomes possible to impose a new constitution. An example of the former is classical republican Rome; whilst an example of the latter is communism.

In Political Theology Schmitt explores the state of exception through two fundamental elements of law: norm and decision. The norm is supsended or annuled to reveal the decision. The state of exception is presented as a theory of sovereignty, since the sovereign is he who can decide on the state of exception and anchor it in the juridical order.

Agamben then loosens Schmitt's tight fit between dictatorship and state of exception. He argues thus:

He says that the state of exception is the opening of a space in which norm and application reveal their separation; between the norm and its application there no internal nexus that allows us to derive on from the other. This marks a threshold in which there is a force of law without the law.

Thus in classical republican Rome the Senate identifies a state of emergency, decides upon a state of exception, suspends the administration of justice and the public law, and decrees that the consuls (or those who act in their stead) are to take whatever measures they considered necessary to ensure the survival of the state.

Agamben argues that this situation indicates that state of excepion cannot be interpreted through the paradigm of dictatorship. What we have is unlimited power being invested from the suspension of the laws that restrict the consuls/magistrates actions. Similarly with Hitler and Mussolini. Hitler was a legitimate Chancellor of the Reich, whilst Mussolini was a legally invested head of government. But characterizes both their regimes is the suspension of the existing constitution and created beside the legal constitution a second structure anchored in the state of exception.

So the state of exception is not a dictatorship as understood by Schmitt. It is:

# a space devoid of law in which all legal determinations are deactivated;

#This space devoid of law seems to be so essential to the juridical order that the state of exception as the suspension of law is grounded in the juridical order;

#The crucial problem connected to suspension is that the acts committed during the suspension seem to be situated in a non-place with respect to the law;

#the idea of the force of law that is separate from the law is a response to the undecidability of this non-place. The force of the law is a fiction through which law attempts to encompass its own absence and to appropriate the state of exception;

#What is at issue in the function of this fiction of 'the force of law' is the definiton of what Schmitt calls 'the political.'

The essential task of a theory of exception is not to clarify whether it has a juridical relation but to define the meaning, place and modes of its relation to the law.

April 5, 2005

pedophilia in politics, emergency measures, constitutional dictatorship

The emergency measures about pedophilia in politics mentioned here, have arisen out of this situation in South Australia. The political background is given by Scott Wickstein over at Troppo Armadillo.

Do the emergency measures indicate a tendency to constitutional dictatorship in liberal democracy?

A step to constitutional dictatorship arises when, in a time of crisis, it is held that a constitutional government must be temporarily altered to whatever degree is necessary to overcome the peril and restore normal conditions.

That is what is happening in SA at the moment. We have a political crisis as a state of exception has been decreed by the Rann Labor Government because of the allegations by the Speaker about pedophilia in high places. Emergency measures are therefore required to deal with the peril, and these require the sacrifice of democracy. It is proposed that parliamentary privilege is to be curtailed and that police can raid parliamentary offices.

What suprises me is how much this happening of a temporary crisis or state of exception is generally accepted. It appears that government of a strong character is what is required to deal with allegations about pedophilia! The body politic is corrupted. Parliament must be protected from itself. The executive comes to the rescue by curtailing the powers of Parliament.

Giorgio Agamben argues that a state of exception is what has become the rule, or the normal. What is the normal in this situation in SA? It is the extension of the powers of the executive against those of Parliament. This extension and dominance of the executive with its sacrifice of democracy is not a transitory phenomena--it is an ongoing tendency of our liberal parliamentary institutions. The existing order that must be preserved is executive dominance.

In the SA example necessity defines the unique situation and it becomes the ground of the law and so included within the juridical situation through an act of Parliament in the name of the right of the state. The state of exception becomes incorporated into the world of law.

The state of necessity becomes subjective as it depends on the aims tha the government wants to acchive. Another government would have a different conception of necessity that requires the emergency measures of withdrawing parliamentary privilege and allowing police to raid Parliamentary offices looking for evidence.

What we see in the SA example is that the suspension of parliamentary order depends upon the opening of a fictitious lacuna for the purpose of safeguarding the existence of the norm of executive dominance.

April 4, 2005

Agamben: State of Exception #3 two examples.

This article by Eric L. Santneron on the University of Chicago Press website links Giorgio Agamben's State of Exception to the Abu Ghraib prison tortures and the Terri Schiavo case.

With respect to the situation of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay Eric says that:

"It is now clear that at Abu Ghraib as well as numerous other detention centers, the problem of prisoner abuse---including clear cases of torture and murder---has not simply been the consequence of a handful of rogue soldiers living out sadistic fantasies on helpless victims. But nor has the problem been one of isolated and contingent miscommunications down the chain of command. The real problem has to do with the legal status of the prisoners themselves and of the sites where they are being detained. With respect to Guantanamo Bay, to cite the most obvious example, the Bush administration has argued that the detention centers there effectively occupy a lawless zone, a site where a permanent (if undeclared) state of exception or emergency is in force. The prisoners have been stripped of all legal protections and stand exposed to the pure force of American military and political power. They have ceased to count as recognizable agents bearing a symbolic status covered by law. They effectively stand at the threshold where biological life and political power intersect. That is why it is fundamentally unclear whether anything those in power do to them is actually illegal."

Places such as Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay represent sites where life, lacking all legal status and protection, stands in maximal exposure to pure political power.

And Terri Schiavo? Eric says that the law passed by Congress that was intended to keep her alive represents:

"... the paradox of an intrusive excess of legal "protection" that effectively serves to suspend the law (the judicial process running its course in the Florida courts) and take direct hold of human life. A law designed to lift a single individual out of an ongoing judicial process is essentially a form or caprice, law in its state of exception (a sanctioned suspension of legality)....To put it simply, if an act of Congress were to lead to the reinsertion of Terri Schiavo's feeding tube, it will not be only water and chemical nutrients that enter her system; it will also be the invasive force of political power."

Are we not standing on the threshold between the human and the inhuman?

In chapter One of State of Exception Agamben says that there is a difference in legal traditions between those who seek to include the state of exception within the sphere of the juridical order and those who consider it something external or essentially political. He says that it better to consider it in terms of a threshold or zone where inside and outside blur into one another.

April 3, 2005

Agamben: State of Exception #2

I managed to abtain a copy of Giorgio Agamben's State of Exception on interlibrary loan on Friday through the Parliamentary Library. I'd ordered it so that I could begin to build on this earlier post by working my way through the book. Alas the book has to be returned on Monday, as it has been recalled by the lending Library.

I'm a little annoyed, as the book looks to be very good. So I cannot work my way through it here. This reading group may suffice until my ordered copy arrives.

The opening pages of the State of Exception state that the state of exception as exceptional measures signifies a temporary abrogation of the rule of law; is a state within the intersection of the legal and the political that represents a no-man's land between public law and poltical fact, between juridical order and life.

Agamben states the paradox nicely:

"...if exceptional measures are the result of of periods of political crisis and, as such, must be understood on political and not juridico-constitutional grounds, then they find themselves in the paradoxical position of being juridical measures that cannot be understood in legal terms, and the state of exception appears as the legal form of what cannot have legal form. On the other hand, if the law employs the exception-- that is the suspension of law itself---as its original means of referring to and encompassing life, then a theory of the state of exception is the preliminary condition of the definition of the relation that bindsand, at the same time, abandons the living being to law."

Agamben argues that in today's political discourse, the state of exception increasingly presents itself as the dominant mode of governing. What had been thought of as a temporary displacement of law, has gradually been becoming the normal practice of governance. The military order and the US Patriot Act that were enacted by the Bush administration after September 11, 2001, serve Agamben as examples of this development.