March 31, 2005

Leo Strauss & political philosophy #2

I mentioned in this post that in his essay, 'What is Political Philosophy', Leo Strauss' response to the hegemony of positivism and historicism in the mid 20th century was to return to the classical political philosophy, and then to defend it against the political philosophy of modernity.

Jacques-Louis David, Death of Socrates, 1787

Strauss takes the classical philosophers seriously. He challenges modern historicism by arguing that we try to understand the classical philosophers as they understood themselves. And that is my problem with Strauss. I cannot see how we can do that. I can only approach the classics from where I am now. There are no skyhooks to lift me out of the present back into the past.I simply cannot dump all my modernist assumptions and think how Aristotle thought.

That is a different argument to the conventional conservative view that leftists today are obliged to denounce Great Books curricula, because wy know, consciously or unconsciously, that classical thought is very much alive and is a real threat to them. Not so. People should read classical political philosophy and engage with it.

I can however accept that the Straussians hold that premodern philosophy is better than modern philosophy and that they are pre-modern and anti-modern in the name of reason, of philosophy: an understanding of reason and philosophy that is different from the Enlightenment's.

Strauss argues that contemporary liberalism is the logical outcome of the philosophical principles of modernity, taken to their extremes. Liberalism, as practiced in the advanced nations of the West in the 20th century, contains within it an intrinsic tendency towards relativism, which leads to nihilism.

I accept that the implication of the argument we should free ourselves from the narrowness of the modern perspective and step back from the distortions and corruptions of modernity.But that does not necessarily mean a return to the ancient point of view towards political affairs. We can go post modern as well as premodern, and go post modern through re-reading the classics.

I can also accept that philosophy calls into question the conventional morality upon which civil order in society depends; it also reveals ugly truths that weaken men’s attachment to their societies. Ideally, it then offers an alternative based on reason, but understanding the reasoning is difficult and many people who read it will only understand the "calling into question" part and not the latter part that reconstructs ethics.

Leo Strauss,therefore, revives the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns when he calls for a return to and a renewal of ancient political philosophy, and in particular that of Plato. Though Strauss argues that he has recovered the original Plato lost sight of by the tradition of Neo-Platonic and Christian interpretation Strauss has not recovered the original Plato, but gives a particular reading of Plato.

March 29, 2005

between history and geography

One familar account of Australia's history goes like this:

"....both convicts and free settlers, of predominantly English, Irish and Scottish extraction, had settled on a land whose location placed them in relative proximity of much larger Asian populations about whom they knew little and with whom they had little or no affinity. White Australia seemed as far as it is possible to be from kith and kin, whereas strangers and potential enemies seemed uncomfortably close."

This has given rise to the white Anglo-Australian heritage whose roots are the deeply ingrained racism of 'White Australia'; a culture of dependency that combines a high degree of insularity with reliance on great and powerful friends; and the tensions between the country's history and its geography.

It is this history that informs the discourse of Australian conservatism, with its emphasis on Australia's 'national character', its 'distinct and enduring values', 'an Australian way of life', deep dependence on the US, strong ambivalence to our inferior and dangerous East Asia neighbours, and anxiety about a multicultural Australia. It is one that stepsteps the colonial treatment of aborigines and displaces the unease and anxiety about that treatment.

March 28, 2005

Giorgio Agamben & Foucault.

Due to this I've started reading Giorgio Agamben's Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1998). I'm impressed by what I've come across so far. Consequently, I've ordered The State of Exception. which I mentioned in in this post as well as Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive (2002). I know very little about the latter.

In starting to read the Introduction to Homo Sacer this afternoon I was suprised by the gaps in the way it tackled Foucault. It starts okay. Agamben says that:

"One of the most persistent features of Foucault's work is its decisive abandonment of the traditional approaches to the problem of power, which is based on the juridico-institutional models (the definition of sovereignty, the theory of the State), in favour of an unprejudiced analysis of the concrete ways in which power penetrates subject's very bodies and forms of life. As shown by a seminar held in 1982 at the University of Vermont, in his final years Foucault seemed to orient this analysis according to two distinct directives for research: on the one hand the study of the political techniques( such as the science of the police) with which the State assumes and integrates the care of the natural life of individuals into its very centre; on the other hand, the examination of the technologies of the self by which the processes of subjectivization bring the individual to bind himself to his own identity and consciousness and, at the same time, to an external power."

So far so good. That concurs with my reading of the Vermont lectures.

The two above tendencies intersect at many points. What Agaamben says nest suprises me:

"Yet at the point at which these two faces of power converge remains strangely unclear in Foucault's work, so much so that it has even been claimed that Foucault would have consistently refused to elaaborate a unitary theory of power...But what is the point at which the voluntary servitude of individuals comes into contact with objective power?...is it legitimate or even possible to hold subjective technologies and political techniques apart...it remains. .. somtehing like a vanishing point that the different perspectival lines of Foucault's inquiry converge toward without reaching."

I would argue that Agamben is wrong on this. The different trajectories of power come together around Foucault's category of governmentality. The connection is made here.

Agamben's failure to mention governmentality is what suprises me.

March 27, 2005

federalism and globalization

A well known effect of globalisation on a sovereign nation-state is the tendency to restrict and undermine Commonwealth's power. The Commonwealth becomes party to international agreements and standard setting and enforcement, and in doing so it restricts the Commonwealth's own independence and autonomy. This can be clearly seen in the economic area with the deregulation of markets, including currency markets and the winding back of tariff protection during the 1980s.

This reduction in the Commonwealth's effective power has been reinforced by the signing of free trade agreements, especially with the US. Australia has been obligated to align its laws with those of the US. The classic example is intellectual property rights regime.

This is certainly a placing of limits on the Commonwealth Parliament dominance that developed during the postwar decades of centralisation.

However, that is not the full picture.Though globalisation is antithetical to the fundamental idea of a sovereign nation-state, it may work differently when the nation-state has a federal system of political governance. As Professor Brian Galligan's parliamentary research paper points out:

"Federalism is essentially a system of multiple governments, divided sovereignty, overlapping and shared jurisdictions, and dual citizenship within domestic governance."

So how does globalization impact on federalism? Galligan suggests that:

"These aspects of federalism make it congenial with an emerging international/national order in which transnational associations and international centres of policy-making and rule setting overlie and intrude into aspects of domestic governance. Likewise, a diffusion of power centres and a variety of institutional systems, each of which has jurisdiction over some matters but none of which is absolute over all the others, are characteristic of both federalism and the emerging international order....In addition there is potential for greater State activity within the umbrella of transnational associations and constrained national government."

Galligan concludes that a likely outcome from increased globalisation might well be a reduced role for the Commonwealth Parliament, compared with its dominance in the postwar decades of centralisation.

He adds that much will depend on the complex politics of this new tripartite system, and the ways in which the Commonwealth Parliament mediates globalisation, or is simply bypassed in direct global/local interactions.

March 25, 2005

Fiscal dominance & Australian federalism

Since 1901 Australian federalism has undergone a sustained process of centralisation. By the end of the century centralist dynamic had reached a point where it had become financially unbalanced.

That unbalance is usually called Australia's extreme 'vertical fiscal imbalance'. This refers to a situation whereby the Commonwealth raises the lion's share of revenue. This fiscal dominance in Australian federalism is due mainly to the Commonwealth's monopoly over income tax and excise duties.

As a research paper from the Australian parliamentary library outlines this monopoly:

"The ...[monopoly over income tax]...was established as a wartime measure in 1942 and upheld by the High Court on grounds other than the defence power in the first Uniform Tax case.(45) The latter is constitutionally grounded in one of the few exclusive powers given to the Commonwealth, but has been interpreted broadly by the Court to include any tax on the production or sale of goods."

The Commonwealth income tax monopoly was imposed by the centralist Chifley Labor Government and a supporting Parliament in time of war, and extended to the subsequent period of postwar reconstruction.The Commonwealth's income tax monopoly was achieved and has persisted because of a combination of political will on the Commonwealth's part, complicity by the States and selective sanctioning by the High Court.

There you have a key to the centralizing dynamic in Australian federalism:---the Commonwealth's fiscal dominance. This dominance is then reinforced by the commonwealth's monopoly over excise duties. As the research paper notes:

"The second revenue pillar of the Commonwealth's fiscal dominance is the preclusion of the States from levying taxes on the sale of goods that are a standard and significant source of revenue for sub-national governments in most other federations. This exclusion is based on the High Court's exaggerated interpretation of its power over 'excise duties' that is one of the few exclusive powers allocated to the Commonwealth by the Constitution (s. 90). Levying customs and excise duties was made an exclusive Commonwealth power in order to ensure a national economic market free of State border taxes and equivalent internal impositions on trade. This constitutional structure and broad interpretation by the High Court explain why the Howard Government's GST was imposed by Commonwealth legislation even though the entire amount collected is to be handed over to the States."

Fiscal centralism that crippled the states was backed and legitimated by the High Court in response to state challenges in the 1940s and 1950s. It was deemed right and proper that the Commonwealth's broad powers that could be used to achieve a fiscal dominance.

However, fiscal centralism had gone too far. Even though fiscal centralism did not spell the end of the States, as they learnt to manipulate the system to retain aspects of State power, the states were financially crippled.

A federal system consists of two spheres of government each pursuing their interests and purposes within the established framework of institutions and powers. It is held that the common good is served and is in effect the product of their actions and interactions.

Usually this interpreted in terms of the Commonwealth Parliament's exercising its powers in ways that give it dominance over, and are at the expense of, the States. The historical justifications have been national defence, national economic management and welfare policies required such dominance.

March 24, 2005

Arendt, Aristotle , politics

Charles Bambach's review of Dana Villa's Arendt and Heidegger:The Fate of the Political in Negations (the Winter 1998 issue) highlights a different way of reading Aristotle. It highlights an interpretation that uses Aristotle against Aristotle. Does this imply a Heideggerian destruction of the political philosophical tradition by Arendt? It is quite different to Leo Strauss's return to the origins by re-tieing the broken thread of tradition.

Bambich outlines the interpretative strategy employed by Arendt that she appropriated from Heidegger:

"What Villa does focus upon... is the way that Arendt's whole style of reading and appropriating the Western philosophical tradition is determined by her adherence to two basic modes of interpretation from Being and Time (1927): retrieval (Wiederholung) and de-construction (Abbau). Simply put, like Heidegger, Arendt's fundamental strategy is to read the tradition not in a spirit of reverence or with the aim of repetition; instead, she attempts to dismantle philosophical concepts, to loosen them from their sedimented and hypostatized strata in order to free them up for a radical kind of retrieval that rethinks their essence from an ontological perspective. Or rather, she wishes to dispense with the whole notion of any subject-centered "perspective" and recover not concepts, but a certain way of being-in-the-world."

Bambich then applies this to Arendt's interpretation of Aristotle to show that Arendt argues against Aristotle. Her theory of action attempts a radical reconceptualization of action, one that proceeds through a critique and transformation of Aristotelian praxis. So the stuff of politics is action, not law or institutions as in liberalism.

Bambich then outlines Aristotle:

'Following Aristotle, Arendt defines the essence of politics as "action." But where Aristotle comes to understand political activity on the model of poiesis as a kind of "crafting" of political life, Arendt breaks with him in order to recover the freedom of political action which she finds in the pre-Socratic tradition. For her, both Plato and Aristotle come to see lawmaking and city-building as "not yet action (praxis), properly speaking, but making (poiesis), which they prefer because of its greater reliability." In other words, they come to define politics as a means and not an end.'

Arendt is recovering Aristotle's conception of praxis in response to liberalism's instrumentalist view of politics as the satisfaction of private interests and preferences. Liberalism's tendency is to reduce the political to the economic, favour a proceduralist conception of democracy and backroom bargaining.

But more than a renewal of Aristotle is happening here. Arendt also engages in a deconstructive reading of Aristotle. This overcoming turns to the categories in the Metaphysics, namely the categories of:

'..."full actuality (energeia) effects and produces nothing besides itself and full reality (entelecheia) has no other end besides itself." By virtue of this solid Aristotelian distinction, Arendt comes to define political action as the last realm of activity in which the human being can experience freedom.'

Bambich says that Villa argues that Arendt then attempts to retrieve the power of the vita activa as a way of critiquing both the liberalism of a consumerist social ethic, as well as the totalitarianism of an instrumentalist bureaucracy in modernity.Both are equated with the European project of technical-instrumentalist activity. This is premised on a modernist self-assertion, which converts everything into a means for some subjectively posited end, and leads to a submission to the technological ordering.

There is a big overlap between Heidegger and Arendt's critique of modernity, with Arendt building on Heidegger's deconstruction of Western philosophy to break with the Western tradition of political thought that has its roots in Plato and Aristotle. It is a breaking that is orientated to recovering another way of being-in-the-world to the technological one of modernity.

March 23, 2005

diverse strands of conservatism

Over at Right Reason some questions about American conservatism are being asked:

"Is modern American conservatism so diverse as to be incoherent? Do the various sub-groups that make up the conservative coalition in America share a common core, beyond the common name of "conservative"?

The response or answer bears on some of the posts on this weblog. The confusions about what conservatism stands for are addressed by mapping the various strands within conservatism in a threefold manner: the paleocon-neocon continuum, the libertarian-state continuum, and the religious-secular continuum. The answer to the above question is that there is a lot of diversity within the conservative tradition.

Robert Koons argues that there is unity within this diversity, if we locate conservatism within the philosophical tradition. He says that:

"Since conservatism is essentially Aristotelianism, it is not surprising that conservatives vary from one another along a number of quantitative parameters. The Aristotelian ideal is that of the political actor who possesses the prudence and judgment required to find, in each circumstance, the appropriate mean. Each mean must be located on along one or more dimensions. Since prudential judgment cannot be reduced to an abstract formula, disagreement among conservatives is inevitable. Despite these disagreements, conservatives remain united by a common Aristotelian ideal and a common set of principles that constrain the disagreements."

I concur with this account. You can see it at work in the conservsatism of Hans-Georg Gadamer. Robert's tradition approach is better pathway than the approach by Irving Kristol.

However, it does not address the positivist position that it is impossible to judge value conflicts, on the grounds that conflicts between different values or goals are not resolvable by reason because they just are personal expressions or preferences.

I would add that Aristotleanism provides an practical reason (phronesis) that overcomes this positivist dead end; as it is an ethical reason that judges the ends of human action in terms of the good life. The good life is unpacked in terms of what constitutes a flourishing life well lived. Hence it is an alternative to an instrumental reason concerned with the most efficient means for pre-given ends. This means that Aristotleanism can provide the ethical/political backbone for lefty's as well as for conservatives.

For instance, in Horkheimer and Adorno Dialectic of Enlightenment, we find a discussion of two conceptions of reason, and the ways in which they have influenced our attitudes towards ourselves and our circumstances. Here is an interpretation of that account:

"The dominant form of reason in an alienated world, according to Horkheimer and Adorno, is what they routinely call instrumental reason. This is the capacity for selecting the appropriate means to our ends, whatever they happen to be. That is, we use reason as an instrument to guide us in attaining our ends. To this type of reason Horkheimer and Adorno contrast another, one which they claim is increasingly rare. It goes by several names, mostly frequently that of objective reason. This type of reason is not instrumental, not concerned with the means to our ends, but instead concerns itself with the ends themselves. It asks whether our ends our rational, whether they express our deepest needs and desires, whether they express our longing for freedom.Horkheimer and Adorno contend that objective reason has been undermined by the Enlightenment, although it should in fact be used to advance the cause of enlightenment. Instrumental reason simply conforms to the ends that we have acquired, telling us how to pursue them in the most effective fashion. Objective reason tells us what our ends should be, and thus it tells us how the world should be, because we are to transform the world in accordance with our rational ends, and thus from how it is into how it should be.

Rather than employing objective reason to discover what our ends should be, Horkheimer and Adorno maintain that our ends are usually imposed on us from without. (This is what Kant called heteronomy.) We acquiesce in what others tell us to think and to do, thereby giving up our independence and failing to achieve autonomy."

Aristotle's phronesis is a form of objective reason that can help us sort out what our ends should be. Simply put the ends of human action is the good life.

March 22, 2005

place

Many academics, professionals, and journalists continue to downplay the importance of place, both as a part of our theory (conceptual structure) as well as as an integral part of everyday human life. Yet people need place because having a place and identifying with a place are integral to what and who we are as human beings. The human experience of place is a fundamental aspect of our existence in the world.

Instead of place as being-in-the-world we have placelessness associated with modernism. This is more than a corporate indifference to particular localities because of standardization in production and consumption as placelessness is also written into our concepts which we use to explain and make sense of the world. A good example is economics. An instrumental economic reason, concerned with the most efficient means for attaining givern ends, has an overriding focus with efficiency as an end in itself Economists, in focusing on the supply and demand, competition and deregulated markets, either ignore place, or reduce it to location.

Some critique this turn to place and sense of place because of its ugly aspects. Places can, for instance, be the basis for exclusionary practices, for parochialism and for xenophobia. There is ample evidence of this in such things as NIMBY attitudes, gated communities and ethnic bigotry and racism.

Hence the turn to borderless world of electronic information and the unprecendented scale of recent global capital and population movements for both migration and tourism.

March 21, 2005

puzzlement

Interesting. I did not know that some members of the Frankfurt School engaged in a critique of Carl Schmitt. But then I have not read the works of Franz Neumann and Otto Kirchheimer, the two legal theorists associated with the first generation of the Frankfurt School.

I do not know what the "social rule of law," means. Nor do I understand this passage:

"Scheuerman argues that Kirchheimer and Neumann have pointed the way beyond the abstract contradiction between social legislation and formal law posited by critics and defenders of the welfare state; he cites New Deal depression legislation in the U.S. as an example that the two need not be mutually exclusive."

What does that mean?

March 20, 2005

Leo Strauss & political philosophy

I picked up a copy of Leo-Strauss' 'What is Political Philosophy?' the other day. It is a collection of essays, lectures and book reviews written in the mid-20th century. This text has surfaced before in this weblog.

In the lead essay, Strauss says:

"Today, political philosophy is in a state of decay and putrefaction, if it has not vanished altogether. Not only is there complete disagreement regarding its subject matter, its methods and its function; its very possibility in any form has become questionable ... We hardly exaggerate when we say that that today political philosophy does not exist any more, except as a matter for burial, i.e., for historical research, or else as a theme of weak and unconvincing protestation."

As a political philosopher in the US Strauss was writing within the hegemony of positivism in academia. He sees political philosophy as being squeezed by two enemies: positivism and historicism.

Strauss acknowledges rightfully understands positivism as maintaining that modern science is the highest form of knowledge; that the social sciences should model themselves on the natural sciences; there is a fundamental difference between fact and value; that value means personal preference; and that science is value-free. That kinda kills off political philosophy as politics departments embrace a positivist political science with enthusiasm.

Strauss also argues that political philosophy is squeezed by historicism. He characterizes this as abandoning the distinction between facts and values because every understanding is evaluative; denies the authoritative character of modern science refuses to regard the historical process as fundamentally progressive; denies the relevance of the evolutionary theiss and rejects the question of the good society.

Strauss decides to fight these two powerful modern currents by returning to the classical political philosophy of Plato and Aristotle; who use the language of citizens and statemen, is concerned with the best regime, virtue and the formation of character. Hence this philosophy is directly related to political life.

This classical tradition was then rejected in modernity in three waves: Machiavelli/Hobbes, Rousseau and German Idealistic philosophy and Nietzsche.

March 19, 2005

University Inc.

The liberal university is often criticized by Christian and social conservatives as one of the last bastions of (left) liberalism, a secular humanist culture and public education. However,this kind of criticism overlooks the way that market forces are dictating what is happening in the world of higher education, and causing universities to look and behave more and more like business enterprises.

This means that instead of the public liberal university honouring its traditional commitment to teaching, disinterested research, and the broad dissemination of knowledge, it is now increasingly becoming the research arm of private industry. Faced with declining government funding, the liberal university has embraced its role as "engines" of economic growth. The promise is that the corporate university will help drive regional economic development by pumping out commercially valuable inventions.

In Australia this neo-liberal redefinition of the university can be traced back to the economic reforms of the 1980s. This mode of governance is premised on universities being able to retain the rights to intellectual property stemming from taxpayer-financed research through public grants. This, it is argued, would stimulate innovation and speed the transfer of publicly financed research to industry.

This neo-liberal mode of governance has meant the introduction of the profit motive into the heart of the university, and the transformation of the liberal university into a corporate business.

The quote below is from a review by Gary Greenberg in Mother Jones of Jennifer Washbourne's book entitled University, Inc. The Corporate Corruption of Higher Education. Washbourne highlights the corporate transformation of the liberal university in modernity:

"This insertion of corporate practices into the academy also yielded a new organism, one that has replicated with great success: the American university reengineered as a bottom-line-oriented big business. Jennifer Washburn's University, Inc. is a painstakingly detailed chronicle of how the free market has penetrated the inner sanctum of higher learning. Schools routinely sell off their research to the highest bidder in deals totaling as much as $1 billion a year. Washburn, who first reported on this trend in an Atlantic Monthly cover story five years ago, believes this partnership of the university with industry is a dangerous development. Not only does it divert universities from their educational goals, but it threatens the public welfare by taking scientific knowledge out of the public domain and placing it under corporate lock and key."

Higher education is no longer about the free exchange of knowledge, as the academic community is now treating basic knowledge as a commodity. This is undermining its traditional role as the guardian of the public domain.

In Australia, we are beginning to see the way that commercial forces are beginning to quietly transform virtually every aspect of academic life. The rise of the corporate university has meant the decline of traditional liberal arts education. Corporate funding of universities is growing and the money comes with strings attached. In return for this largesse, universities are acting more and more like for-profit patent factories, while professors are behaving more like businessmen. Secrecy is replacing the free flow of basic knowledge,university funds are shifting from the humanities to more commercially lucrative science labs, and the skill of teaching is valued less and less.

University, Inc. illustrates what is being undermined: the privatisation of knowledge undermines public health and the "knowledge commons" established in modernity. The questions put on the table are: 'Who owns and controls university-produced knowledge? Who should own it, and who should benefit from it?'

March 18, 2005

A quote:

"The United States flaunts the banner of democracy in the Middle East only when that advances its economic, military, or strategic interests. The history of the past six decades shows that whenever there has been conflict between furthering democracy in the region and advancing American national interests, U.S. administrations have invariably opted for the latter course. Furthermore, when free and fair elections in the Middle East have produced results that run contrary to Washington's strategic interests, it has either ignored them or tried to block the recurrence of such events."

The quote is from Dilip Hiro's article 'How America Furthers Its National Interests in the Middle East.' It can be juxtaposed to the rosey view of John Rawls mentioned here.

March 17, 2005

A liberal International Order #2

What I found of interest in Perry Anderson's article on external relations between nation-states, 'Arms and Right: Rawls, Habermas and Bobbio in an Age of War', that I mentioned earlier is the way these philosopher's concerns for a desirable liberal international order deal with American hegemony or Empire. I remember glancing through Rawls' The Law of Peoples and not being very impressed.It did not seriously address the issue of the US as a global hegemon. Anderson concurs.

According to Anderson:

"Rawls describes his Law of Peoples as a 'realistic utopia': that is, an ideal design that withal arises out of and reflects the way of the world... [For Rawls] veneration of totems like Washington and Lincoln ruled out any clear-eyed view of his country's role, either in North America itself or in the world at large. Regretting the us role in overthrowing Allende, Arbenz and Mossadegh---'and, some would add, the Sandanistas [sic] in Nicaragua': here, presumably, he was unable to form his own opinion---the best explanation Rawls could muster for it was that while 'democratic peoples are not expansionist', they will 'defend their security interest', and in doing so can be misled by governments. So much for the Mexican or Spanish-American Wars, innumerable interventions in the Caribbean, repeated conflicts in the Far East, and contemporary military bases in 120 countries. 'A number of European nations engaged in empire-building in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries', but--so it would seem--happily America never joined them."

This is pretty standard US liberal position.We are not an empire because we are not colonizers like the Europeans. And the bases, invasions and unilaterial actions? America is the champion of liberty, democracy and law--look at our record in the twentieth century with respect to the two world wars.

That was yesterday. Has not the US built an empire of bases rather than colonies, creating in the process a government that is concerned with maintaining military dominance over other nations? The American republic is becoming an empire.

March 16, 2005

Giorgio Agamben & ethos

I'm continuing to work my way through Adam Thurschwell's very dense 'Spectres of Nietzsche: Potential Futures for the Concept of the Political in Agamben and Derrida'. I've skipped the political/legal philosophy of Jacques Derrida in favour of Giorgio Agamben.

The reason for my attraction is his understanding of ethics: it is an understanding of ethics ethos, connected to one's life as potentiality, to a human abode and to the happy life, which is developed in the book Language and Death.

Ethos is the habitual dwelling place of human beings and it is the mode in which we are most at home. Ethos as a habitual dwelling place is a very Heideggerian understanding of ethics.

March 15, 2005

ethics and politics

I was ploughing through an academic article on the political/legal philosophy of Jacques Derrida and Giorgoi Agamben and their relationship to Nietzsche on the plane to Canberra on Sunday night. The article by Adam Thurschwell is entitled ('Spectres of Nietzsche: Potential Futures for the Concept of the Political in Agamben and Derrida'. I was reading it because of this post, on Agamben's The State of Exception.

I cannot recall where I found Thurschwell article online. In The German Law Journal perhaps?

There was a passage in Thurschwell's article that I found both interesting and puzzling. It talked about the absolute break between the ethical and the political in, I presume, late modernity. I say absolute because the sense of the passage, and others similar to it, was of an unbridgeable gap between the ethical relationship and any given form of politics. Thurschwell says that this absolute break, gap or gulf is accepted as a given by both Derrida and Agamben and is the reason why they have embraced the vocabularly of messianism.

Why so I thought? Is the absolute gulf because of positivism? Or nihilism? It didn't make sense because positivism makes the gulf between scientific fact and emotivist ethics, and so both ethics and poltics are expressions of personal emotions. Nihilism says that our highest values have beeen devalued.

Hence my puzzlement about the assumption of an unbridgeable gap between ethical relationships or ethos and any given form of politics.

Then I recalled Robert Menzies collection of Wartime speeches, The Forgotten People, with its appeal to people in small business or who come into politics as individuals, bearing particular character qualities. This linked ethics and politics.

These people were of good character, they saw themselves as virtuous, and it was because they saw themselves as virtuous, as having particular character qualities that they believed that they were the backbone of the nation, and hence fit to govern and hold political power.

There is no great divide between ethics and politics in this continuous political tradition. It's appeal is to individualism, the virtues, and to the home as the place of the individual with their private aspirations and the ground ground of virtue ethics.The virtues draw deeply on Protestantism (Puritan ethic) and these are coupled to a self-realization ethic that every individual should have the opportunity to develop their personality and capacities to the fullest extent.

March 13, 2005

a liberal international order

Here is an article on external relations between nation-states by Perry Anderson to read whilst I make my way back to Canberra. Entitled 'Arms and Right: Rawls, Habermas and Bobbio in an Age of War', it deals with these philosopher's concerns for a desirable liberal international order.

Both Rawls and Habermas refer back to Kant's utopian 'For a Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch of 1795.' I say utopian because Kant, as Anderson says:

"Kant had believed, by the gradual emergence of a federation of republics in Europe, whose peoples would have none of the deadly impulses that drove absolute monarchs continually into battle with each other at the expense of their subjects---the drive for glory or power. Rather, interwoven by trade and enlightened by the exercise of reason, they would naturally banish an activity so destructive of their own lives and happiness."

This never happened in the 19th or the 20th century. Is it happening with the UN? Does Kant's vision come to life after 1945?

Anderson says that Habermas thought so. Anderson briefly outlines Habermas' take on Kant:

"Kant's institutional scheme for a perpetual peace has proved wanting. For a mere foedus pacificum---conceived by Kant on the model of a treaty between states, from which the partners could voluntarily withdraw---was insufficiently binding. A truly cosmopolitan order required force of law, not mere diplomatic consent....The transformative step [that is] still [needed] to be taken [is] for cosmopolitan law to bypass the nation-state and confer justiciable rights on individuals, to which they could appeal against the state. Such a legal order required force: an armed capacity to override, where necessary, the out-dated prerogatives of national sovereignty."

Anderson says that the first Gulf War was evidence that the United Nations was moving in this direction, and he suggests that, for Habermas, the present age should be seen as one of transition between international law of a traditional kind, regulating relations between states, and a cosmopolitan law establishing individuals as the subjects of universally enforceable rights.

If this is so, then does not the UN lack a mechanism for the resolution of conflicts and the enforcement of individual rights?

Habermas is critical of the nation-state and he sees its power as weakening two broad forces. Anderson says:

"On the one hand, globalization of financial and commodity markets are undermining the capacity of the state to steer socio-economic life: neither tariff walls nor welfare arrangements are of much avail against their pressure. On the other, increasing immigration and the rise of multi-culturalism are dissolving the ethnic homogeneity of the nation. For Habermas, there are grave risks in this two-sided process, as traditional life-worlds, with their own ethical codes and social protections, face disintegration."

This leads to a post-national constellation with the European Union offering a model in which:

"..the powers and protections of different nation-states were transmitted upwards to a supra-national sovereignty that no longer required any common ethnic or linguistic substratum, but derived its legitimacy solely from universalist political norms and the supply of social services. It is the combination of these that defines a set of European values, learnt from painful historical experience, which can offer a moral compass to the Union."

Such a European federation, marks a historic advance beyond the narrow framework of the nation-state. How do we go further than that in terms of a post-national constellation? Certainly not to world government, which is not on the agenda. What we can do is vault the barriers of national sovereignty through human rights.

March 12, 2005

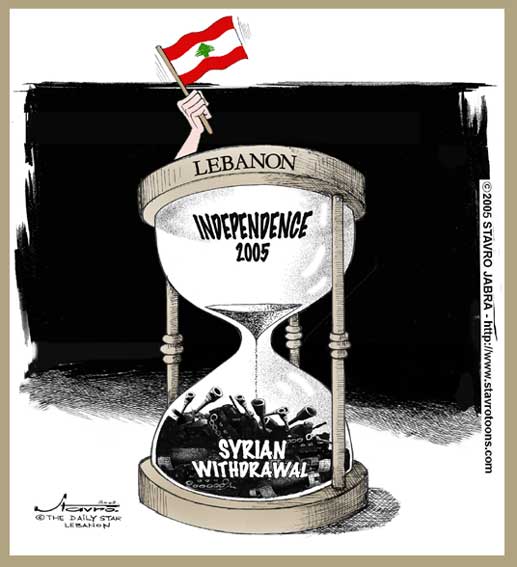

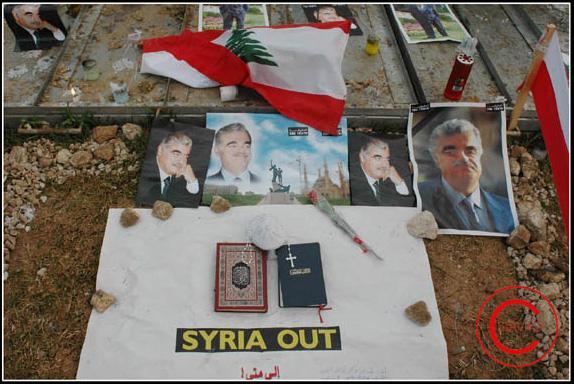

Lebanese Independence#3

Syria's tactic appears to be one of drawing out its military withdrawal from Lebanon so as to break the unity of its Lebanese opponents.

Will the Syrian retreat reopen the sectarian (Christian-Muslim) divisions of the 1975-1990 Lebanese civil war? Will Lebanon once again fall into the abyss?

The half a million Lebanese Shias who marched last Tuesday did pose a challenge to President George Bush's project in the Middle East, and to his demands for a Syrian withdrawal from Lebanon and the disarmament of the Hizbollah guerrilla movement.

Robert Fisk asks a good question:

"So what did all this prove? That there was another voice in Lebanon. That if the Lebanese "opposition" - pro-Hariri and increasingly Christian - claim to speak for Lebanon and enjoy the support of President Bush, there is a pro-Syrian, nationalist voice which does not go along with their anti-Syrian demands but which has identified what it believes is the true reason for Washington's support for Lebanon: Israel's plans for the Middle East."

Will the Syrian military retreat to the Syrian side of the frontier, or will they sit in the Lebanese-Armenian town of Aanjar, on the Lebanese side?

Update

The anti-Syrian pro-Rafik Hariri democratic movement has responded to the pro-Syrian movement with a huge demonstration.Abu Aardvark has some comments on the way the media are interpreting these opposing crowds in Lebanon and their political meaning.

The Heed Heeb observes:

"The size of the Hizbullah and opposition demos should also put paid to the theory that either side was manufactured ex nihilo by foreign interests. It simply isn't possible to mobilize crowds that size in a nation of four million without genuine popular support. In fact, as Mary Wakefield points out (via Issandr), there are two legitimate popular movements in Lebanon right now, both of which are well organized and have closely studied popular protests in other countries. The debate over Lebanon's future has been unleashed, and although each side might look to allies in the outside world for support, it is fundamentally a Lebanese debate."

A Lebanese debate about what?

March 11, 2005

Lebanese independence

The death of Rafik Hariri, the former Lebanese prime minister and symbol of Lebanon's post-civil war regeneration, has sparked a democratic political movement in Lebanon:

The political desire for national liberation by the Hariri demonstrators is clearly expressed. Robert Fisk's commentary describes this desire:

'Never has a Lebanese government been so shunned by its people. Never have the Syrians faced such united opposition from the people they claim to "protect" with their 15,000 troops and their intelligence services. Rafik Hariri's family angrily turned down the offer of a state funeral from their pro-Syrian Lebanese President. Instead, the funeral of the murdered former prime minister yesterday turned into an independent march in which hundreds of thousands of Muslims and Christians who were fighting to the death in the civil war walked together in shared mourning and friendship.There was not a gun in sight. Not a shot was heard. Down to the Martyr's Square---the old front line which divided this country for 15 years of war---they walked, shouting: "Syria Out, Out, Out."'

The Hariri political movement was countered by the Hizbollah-organised pro-Syrian demonstration last Tuesday, which drew half a million people. Did this massive demonstration assert the legitimacy of Syrian as an occupier of Syria by the Lebanese street? Or are the Lebanese Shia political demands more complex? Do they interpret "the right of the Lebanese people to determine their future free from domination of a foreign power to mean freedom from the domination of the United States and Israel and not Syria? Or all three?

March 10, 2005

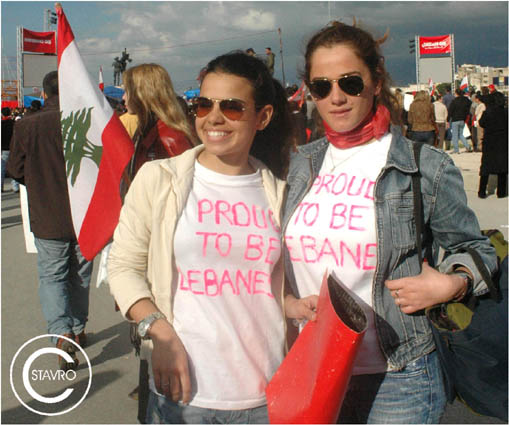

Lebanon: democracy & independence

These photos of democratic stirring in Lebanon were taken by the Lebanese cartoonist Stavros:

It is a democratic movement that wants Lebanon for the Lebanese:

The political desire of the Hariri protesters is national independence from foreign (Syrian) occupation. The Lebanese people have the courage to demand that Syria stop meddling with their affairs.

March 9, 2005

An Australian Enlightenment?

This book review by Keth Windshuttle of Gertrude Himmelfarb's 'The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments' highlights two kinds of Enlightenment. Windshuttle says:

"Most historians have accepted for several years now that the Enlightenment, once popularly characterized as the Age of Reason, came in two versions, the radical and the skeptical. The former is now generally identified with France, the latter with Scotland. It has also been acknowledged that the anti-clericalism that obsessed the French philosophes was not reciprocated in Britain or America. Indeed, in both these countries many Enlightenment concepts ---human rights, liberty, equality, tolerance, science, progress —--complemented rather than opposed church thinking."

Windshuttle says that Himmelfarb's historical account states that:

"..unlike the French who elevated reason to the primary role in human affairs, British thinkers gave reason a secondary, instrumental role. In Britain it was virtue that trumped all other qualities. This was not personal virtue but the "social virtues"----compassion, benevolence, sympathy----which the British philosophers believed naturally, instinctively, and habitually bound people to one another."

I suspect that Windshuttle is saying that the Australian Enlightenment would follow the British one, and so it would also stand in opposition to the French one. This is suggested by Windshuttle saying that we have inherited the differences between the two Enlightenment's.

Windshuttle says:

"...have remained to this day, and over much the same issues. On the one hand, in France, the ideology of reason challenged not only religion and the church but all the institutions dependent upon them. Reason was inherently subversive. On the other hand, British moral philosophy was reformist rather than radical, respectful of both the past and present, even while looking forward to a more enlightened future. It was optimistic and had no quarrel with religion, which was why, in both Britain and the United States, the church itself could become a principal source for the spread of enlightened ideas."

On Windshuttle's reading Australia takes the pathway of the social virtues (sympathy and benevolence as moral virtues) and not reason. He concludes his review by saying that these ideas and practices were born they still firmly mold the moral sense and common sense of the English-speaking world today.

I'm not convinced by this revisionism for two reasons. First, reform in Britain came from the Benthamite utilitarians who take the reason and utility, not the social virtues (sympathy and benevolence). Australia followed suit. It is a nation-state ruled by a reformist Benthamite utilitarianism.

Secondly, Windshuttle downplays the anti-modernist Catholicism that stood in opposition to political liberalism. In Australia this anti-modernism was represented by Santamaria and Archbishop Mannix that resulted in the 'Split' in the ALP in the 1950s and by Cardinal Pell today. Pell wages the fight against liberal modernity within the Catholic Church.

March 8, 2005

Description of Australia

Fred Halliday is in Australia. Some observations:

"Howard, a tough politician with a sharp tongue and good instincts for the popular mood....has presided, in domestic and foreign policy, over a significant reorientation of the country, away from the more liberal and multicultural attitudes of the 1980s and early 1990s. The shift brings Australia closer at once to the values and aspirations of the "White Australia" of the post-war, Robert Menzies era and to the worldview of the contemporary United States of America. In current European terms, by combining domestic conservatism and pro-American foreign policy to secure election victory, Howard is following the Danish path rather than its opposite, the Spanish.".

Halliday comments that immigation and aboriginal issues have swung Australia away from being a multicultural society. He adds that these:

"...trends in government policy have been accompanied by a rise in nationalist culture [that]lends itself to multiple modern associations – Australian heroism, a Muslim enemy....The paradox of Australia...is its combination of isolation and fear. One result of its sense of great distance from its natural allies in Europe and the US, and its persistent nervous awareness of its giant Asian neighbours to the north...is a feeling of vulnerability."

He ends by saying that Howard has little time for New Zealand's socialist and liberal values; like Rupert Murdoch, he promotes what is, in effect, the Americanisation of Australia's public life.

March 7, 2005

An article by John Kekes on conservatism. It begins thus:

Conservatism is a political morality. It is political because it aims at political arrangements that make a society good, and it is moral because it holds that a society is good if it enables people living in it to live good lives, that is, lives that are personally satisfying and beneficial for others. Conservatism, like liberalism and socialism, has different versions, partly because conservatives often disagree with each other about the particular political arrangements that ought to be conserved. There is no disagreement among them, however, that the reasons for or against those arrangements are to be found in the history of the society whose arrangements they are. This commits conservatives to denying that the reasons are to be derived from a hypothetical contract, or from an imagined ideal order, or from what is supposed to be beneficial for the whole of humanity. In preference to these and other alternatives, conservatives look to the history of their own society because it exerts a formative influence on their present lives and on how it is reasonable for them to want to live in the future.

How many Australian conservatives who defend traditional puritan bourgeois values think like that? It is not even clear that Australian conservatives are committed to political arrangements that foster good lives, or have a view about what lives are good. They do have a sense of what obligations, virtues, and satisfactions are worth valuing, but it is unclear that they connect this concern with traditional bourgeois values to the values that make lives good.

Making lives good is alien because Australian conservatives link their values, obligations and virtues to a prosperous economy and not to good lives.

March 6, 2005

I'm on the road to Canberra. I'll post on Derrida and democracy here when I can, either later tonight or early tomorrow morning.

March 5, 2005

Universities in the marketplace

I'm busy applying for jobs.

An article on the university in The New York Review of Books by Andrew Delbanco entitled the 'Endangered University.'

Dam, I've just noticed that the article is locked. I'll have to find a hard copy of it. I was particularly interested in Derek Bok's 'Universities in the Marketplace: The Commercialization of Higher Education' for its insight into universities now seeking opportunities to turn specialized knowledge into profit in a knowledge-based economy; and James O. Freedman's 'Liberal Education and the Public Interest' for the connection between universities, democracy and eduction for citizenry.

March 4, 2005

Joseph Stiglitz: Four quotes

These quotes about intellectual property rights are from Joseph Stiglitz's The Roaring Nineties: Why We're Paying the Price for the Greediest Decade in History,

"Intellectual property rights typically make some better off (the drug companies) and many worse off (those who otherwise might have been able to purchase the drugs)." [p.209]

"Market economies only lead to efficient outcomes when there is competition and intellectual property rights undermine the very basis of competition."[p.208]

"Patents often represent privatization of a public resource, of ideas that are largely based on publicly funded research."[p.208]

"Intellectual property rights need to balance the concern of users of knowledge with those of producers. Too tight an intellectual property regime can actually harm the pace of innovation; after all, knowledge is the most important input into the production of knowledge. We knew that the argument that without intellectual property rights, research would be stifled was just wrong: in fact, basic research, the production of ideas that underlay so many of the advances in technology, from transistors to lasers, from computers to the internet was not protected by intellectual property rights . . . "[p.208]

The quotes are taken from this review in Logos

March 3, 2005

the public university

An article on the public university by in The New York Review of Books by Andrew Delbanco.In Australia as in the US the expansion of the public university is over. The reversal comes from declining public funds and increasing tuition fees in our public universities and the rise of private universities and the entry of the electronic universities into the educational marketplace.

It is a fundamental transformation. Does that mean a good education is being reconnected with privilege and wealth? The period of the public university, a liberal education and education for democracy is coming to a close? It is now increasingly about working full-time, going to uni part-time and majoring in subjects with immediate utility?

A key problem with our public universities is that they have been gutted of funds. This has lead to a lack of jobs, lack of pay for part-time work (and the highly exploitative casualisation of our university workforces) and a limp intellectual culture.

March 2, 2005

The demolition of the Constitution

You don't often have op-eds on the Australian Constitutionin the Australian press. But Greg Craven had one yesterday in The Australian entitled, Betrayal of Menzies. Since the article will disappear after a few days I will spell Craven's argument out.

The usual attitude to the Australian constitution is that it's federal division of powers apply the brakes to the economy. As the Australian Financial Review states:

"This division does not reflect current realities or help us to solve national problems in a timely way. Federalism's division of powers work well as a bulwark against undue concentration of power in any one level of government. But it tangles up the lines of accountability and financial responsibility between the three levels of government and the institutions they control, from schools and hospitals to railways, ports and industrial relations. This makes it hard to deal with emerging problems such as labour, skills, and infrastructure shortages until they are verging on crisis, and encourages buckpassing, cost-shifting and name-calling."

Craven thinks otherwise to this economic thinking. He defends federalism, and argues that Australian political elites have tried to undermine the federal principles. Craven says:

"Historically, it has been the Australian Left that has reviled the Constitution. Most recently, the Left has found deeply trying the Constitution's dogged refusal to invest unelected judges with absolute power over human rights and it has hurled its anathemas accordingly.But, long before this, Labor and its allies loathed the Constitution on a quite different score. They longed to dismantle its clanking federalism and replace it with an efficient centralising apparatus that would usher in all forms of marvels, from wage control to price fixing. From Billy Hughes to Gough Whitlam, Labor did battle with Australian constitutional federalism. Casualties were heavy on both sides but, if Labor gave the states as good as they got, it never quite managed to get the states."

I pretty much accept this interpretation of the ALP's position this battle over federalism during the 20th century.In this battle the political right has defended federalism.

Greg Craven says:

"Throughout these battles...the Australian political Right stood with the Constitution and its inherent federalism. It did so not only out of a desire to frustrate Labor's agenda for social and economic control but also from a deep if vague understanding of the link between federalism on the one hand, and notions such as liberalism, conservatism and even democracy on the other.Liberals, such as Robert Menzies, harking back to the great constitutional founders such as Alfred Deakin and Edmund Barton, comprehended that federalism was not just a regrettable historical reality of Australian government. Quite beyond that, federalism was an organising principle of government designed to protect just those qualities of freedom, balance, community and difference dear to liberals and conservatives."

The standard reference to state rights tends to short circuit this broader understanding of federalism.

What then is the principle of federalism? Craven does not disappoint on this.

First,

"...federalism first promotes freedom by balancing the powers of two spheres of government, one against the other, so ensuring that in Australia there is, by definition, no totality of power. Moreover, the existence of these two spheres guarantees competing public dialogues of power, ensuring that few policy balls go through to the keeper unremarked in Australia.Consequently, from education and health to industrial relations and the environment, there is no sphere of government in Australia that is all-powerful and none whose proposals cannot be subjected to an organised critique from a fellow government."

The second principle of federalism is that:

"....federalism ensures (or aims to ensure) that the policy issues closest to regional communities are determined substantially by those communities by committing those issues to local state governments, not the remote bureaucracy of Canberra. In so doing, it not only magnifies local democracy but also promotes decisions practically adapted to local conditions and difference.Balanced power, contained government, local control of local affairs and respect of regional difference: there hardly could be a governmental creed more palatable to conservative tastes."

Yet the political wheel turns. Today it is the conservatives who are out to demolish federalism. Craven says:

"...the Howard Government is spitting out Australian federalism like so much constitutional gristle. In its casual abandonment of its federalist conservative heritage, the administration of John Howard appears to have embarked on the greatest centralisation of power in Australia since World War II. Then, at least, inroads on Australia's federal character could be justified as a response to the demands of total war...In their unadorned determination to exploit power while the going and the Senate is good, many of Howard's ministers display no parallels with a Deakin or a Menzies, who reluctantly understood that constitutional restraints on the untrammelled exercise of power are a given good, even if--and perhaps especially when--they most irritatingly restrain you."

And irony of ironies, says Craven, the conservative politicians resemble the old leftist social engineers they profess to despise who, having briefly stormed the citadels of power, will brook no inhibition or argument against the full implementation of their program of the hour.

The new conservatives are, in short, neither liberals nor conservatives with a respect for balance and restraint but merely politicians in the usual self-important hurry towards eventual, inevitable replacement by their opponents.

That's the Craven account. I agree with it, even on I'm on the left.

March 1, 2005

T. H. Green, social liberalism, positive freedom

A review of T.H. Green's Theory of Positive Freedom: From Metaphysics to Political Theory by Ben Wemde in The Guardian. It is a poor review, but Green's ideas are important today, as they provided the springboard to go beyond a laissez-faire or market liberalism. Social moral rights (those that are recognised as contributing to the common good), not the market, should determine the positive freedoms we are able to enjoy in a nation state.

Green is important in Australia as his ideas on positive freedom provided the philosophical backbone for the welfare state for the social democracts in the Labour party. There is a tradition in the ALP that dislikes philosophers, is openly contemptuous of the speculation of political philosophy, and works with a pragmatic 'fair go' for the industrial working class. It is a tradition that turns its back on the philosophical backbone of social liberalism.

Green developed a political philosophy that rejected the atomistic individualism and empiricist assumptions that underpinned classical liberalism and develeoped a political philosophy based around four notions: the common good; a positive view of freedom; equality of opportunity; and an expanded role for the state.

Positive freedom, as the power or capacity of doing something, meant legislation by the ethical state to require employers to take responsibility for protecting their workmen against industrial injuries. This step beyond negative freedom (freedom from) also meant the state providing pension, unemployment benefits and public health and education from the general taxation of the population.

Sick people, as a self-determining agents, do not have the capacity to work. So the state should provide a public system to help people overcome sickness. What makes the state ethical is a concern for the wellbeing (individual self-realization) of its citizens.

The Standford Encyclopedia entry on Green says:

"Green holds that the state should foster and protect the social, political and economic environments in which individuals will have the best chance of acting according to their consciences. ...Yet, the state must be careful when deciding which liberties to curtail and in which ways to curtail them. Over-enthusiastic or clumsy state intervention could easily close down opportunities for conscientious action thereby stiffling the moral development of the individual. The state should intervene only where there was a clear, proven and strong tendency of a liberty to enslave the individual. Even when such a hazard had been identified, Green tended to favour action by the affected community itself rather than national state action itself---local councils and municipal authorities tended to produce measures that were more imaginative and better suited to the daily reality of a social problem. Hence he favoured the 'local option' where local people decided on the issuing of liquor licences in their area, through their town councils."

The national state itself is legitimate for Green to the extent that it upholds a system of rights and obligations that is most likely to foster individual self-realisation.