June 30, 2005

Reading Hegel's Phenomenology

Someone has been reading Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit. How about that, eh? People are actually engaging with this text.

I should say 'struggling' rather than reading, as the reading is a struggle to make sense of what one is reading. It is made difficult because the text challenges one's own presuppositions that have developed from living in an empiricist culture.

I had been intending to struggle with this text during my holidays to sharpen up the mind. It is kinda like pianists doing the scales.

Here is a little passage from the very difficult and dense Preface that I remember:

"Truth and falsehood as commonly understood belong to those sharply defined ideas which claim a completely fixed nature of their own, one standing in solid isolation on this side, the other on that, without any community between them. Against that view it must be pointed out, that truth is not like stamped coin that is issued ready from the mint and so can be taken up and used..." (para.39)

You can read passages of Hegel not understanding a thing. You fall into despair. How can I ever make sense of this stuff? This is impossible. Nobody should be allowed to write like that etc etc.

When you re-read it, slowly, working to understand what the passage is saying line by line, then it does not seem so alien on the surface. Feeling a bit more confident you rea d it. Okay, you say to yourself, that wasn't too bad. So you read on.

Then you hit a passage that sort of clicks:

"Dogmatism as a way of thinking, whether in ordinary knowledge or in the study of philosophy, is nothing else but the view that truth consists in a proposition, which is a fixed and final result, or again which is directly known. To questions like, "When was Caesar born?". "How many feet make a furlongs", etc., a straight answer ought to be given; just as it is absolutely true that the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides of a right-angled triangle. But the nature of a so-called truth of that sort is different from the nature of philosophical truth."

You may not know what Hegel means by philosophical truth, but you get the idea of truth as a proposition. Then you think of early Betrand Russell and the origins of analytic philosophy, logic and the philosophy of language----and away you go chasing hares through the tangled undergrowth.

But you come back to the idea that there is another kind of truth to the one accepted by mathematics, empiricism and science. Suddenly a different world opens up. You gulp, as you realize you are going to start on a philosophical journey that is going to take you to some very strange lands. You know that the experience of reading The Phenomenology is going to change you. You are going to be quite different as a result of the experience.

It took half an hour to read a couple of paragraphs--about half a page. Only several hundred to go.

June 29, 2005

Peter Saunders on Weber and ethics

There is a bit of a debate about higher education happening in the Australian blogoshpere. See here and here for the contributions from Catallaxy; see here for Troppo Armadillo and for public opinion.

What I want to raise here is the comments by Peter Saunders made on this post. Saunders says that Max Weber said it all a century ago in his essay on 'Science as a vocation':

"Science today is a 'vocation' organized in special disciplines in the service of self-clarification and knowledge of interrelated facts. It is not the gift of grace of seers and prophets dispensing sacred values and revelations, nor does it partake of the contemplation of sages and philosophers about the meaning of the universe.And if Tolstoi's question recurs to you: as science does not, who is to answer the question 'What shall we do, and, how shall we arrange our lives?'--- Then one can say that only a prophet or a savior can give the answers. If there is no such man, or if his message is no longer believed in, then you will certainly not compel him to appear on this earth by having thousands of professors, as privileged hirelings of the state, attempt as petty prophets in their lecture-rooms to take over his role."

Ethics is radically separated science as are values from facts. The consequence is that an ethics concerned about the good life is reduced to the voice of the prophet or a savior, when it is actually a part of our comportment in everyday life.

Now Saunders recognizes this.

He says that the Weber is concerned about the dangers in the growth of instrumental rationality, and he warns against the 'cult of the expert' in the modern world and argues in favour of a radical separation of facts and values, science and politics. He says:

"Sometimes his [Weber's] concern [have] been interpreted as wanting to preserve science from value judgements, but he is much more concerned to preserve ethical debate from contamination by spurious claims to expertise. Weber wants us to recognise that we have to make our own ethical choices from among the 'warring gods' of ultimate values, and that nobody can resolve these ethical dilemmas for us. He thinks there is a real danger of academic experts trying to subvert or pre-empt this moral world by telling us what to think."

The implication of Weber's positivism is that a moral vacuum arising from an emotivist conception of ethics (it's merely personal preferences) which allows academics posing as experts to decide the ethical choices.

We can refuse the emotivism that is accepted by Saunders.

June 27, 2005

Hegel: Phenomenology of Spirit

I spent many years of my academic life diligently working my way through Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit. I did so because I recognized its influence on later philosophers (its anti-foundationalism, the master-slave dialectic and the development of recognition). But I struggled with the impenetrability of the prose and often found myself reading whole pages without understanding a word. I read a page again, then get a glimmer, then read it again and the glimmer would become an insight.

It was hard work: the intellectual equivalent of hard labour.I poured over every secondary text---though not Heidegger's--- and came out favouring an historicist reading (the sociality of historical reason), not a Platonic one. I hung onto that insight like a dog on a bone.

The Phenomenology of Spirit was not a text that you could teach in a gum tree university that was undergoing big changes (downsizing of the humanities) from the effects of neo-liberal mode of governance. Hegel presupposed a great familiarity with other philosophical views, the difficulties they faced, and the major responses to these within the philosophical tradition. Few students had that kind of knowledge--it took a decade to acquire a rough grasp, and it was very unlikely that an Australian university would give you that education. You had to go to the US to gain such an education.

So I taught a portion of this extremely difficult and obscure text. I kept on reading and re-reading Hegel (Philosophy of Right, Philosophy of Nature, the Logic, Lectures of History of Philosophy etc) because of his central importance to modern philosophy. I bloody well lived Hegel for a decade without ever feeling that I got him nailed.

A passage from the difficult Preface, which is the preface to the Phenomenology and to Hegel's larger system mappedout in the Encyclopedia:

"...this gradual development of knowing, that is set forth here in the Phenomenology of Mind. Knowing, as it is found at the start, mind in its immediate and primitive stage, is without the essential nature of mind, is sense-consciousness. To reach the stage of genuine knowledge, or produce the element where science is found---the pure conception of science itself---a long and laborious journey must be undertaken ... The task of conducting the individual mind from its unscientific standpoint to that of science had to be taken in its general sense; we had to contemplate the formative development (Bildung) of the universal [or general] individual, of self-conscious spirit. As to the relation between these two [the particular and general individual], every moment, as it gains concrete form and its own proper shape and appearance, finds a place in the life of the universal individual. The particular individual is incomplete mind, a concrete shape in whose existence, taken as a whole, one determinate characteristic predominates, while the others are found only in blurred outline."

Thus we have the formative development (Bildung) of historical reason. Of course, this development of the coming-to-be of knowledge, is driven by contradictions. You can see where Marx got a lot of his ideas about how capitalism works.

The Phenomenology is generally seen as the preface to Hegel's larger system with the last chapter of the Phenomenology providing a relation or bridge . . . to the beginning of the Logic. The Phenomenology can be seen as a stand alone text that makes the case for the need of a new way of knowing--the historicity and dialectical development of reason; a new way of knowing that stands in oppostion to the mathematical way of knowing favoured by Descartes, modern physics and now neo-classical economics.

June 26, 2005

Agamben: state of exception

In the few moments that I have in finishing one job and finding another I am reading Giorgio Agamben's State of Exception, the sequel to Agamben's Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. This is Volume III of Homo Sacer, and it takes its point of point of departure from Carl Schmitt's Political Theology which describes the state of exception as a kind of legal vacuum, a 'suspension of the legal order in its totality.'

We have been here before, and understood that Agamben is arguing here that the state of exception, which was meant to be a provisional measure, has became in the course of the twentieth century a normal paradigm of government. The text is theorizes the generalization of the state of exception" in its historical and philosophical context.

June 24, 2005

Agamben: 'Muselmann'

In Giorgio Agamben's Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive there is a detailed discussion of the Muselmänner (or 'muslim') of the Nazi concentration camps.

Muselmann was the term used by internees in the camps to describe 'the walking dead' of the camps, those who through exposure to starvation, deprivation, violence and brutality experience a fundamental "loss of will and consciousness" (p.45). s Catherine Mills states that Agamben finds in this figure is the limit condition of human life. She says:

"The term 'Muselmann' refers to those in the camps who had reached such a state of physical decrepitude and existential disregard that 'one hesitates to call them living: one hesitates to call their death death' (Levi cited in Agamben: 1999: 44). 'Muselmann' names the 'living corpses' that moved apparently inexorably toward death in the camps, beings who, through exhaustion and circumstance, had lost the capacity for living. They are the 'anonymous mass' that formed 'the backbone of the camps'.."

There has been a suggestion that the Muselmann is the true witness of the camps even though they cannot speak. If so, then the task of bearing witness is at base a task of bearing witness to the impossibility of witnessing.

June 22, 2005

Does freedom necessarily mean liberation from power relations?

No.

Power relations are an integral part of the everyday life. We live within them. That is what you learn when you work within political institutions such as the federal parliament. Power relations are part of every day life in the political sphere.

June 21, 2005

about Foucault's understanding of power

In reading the Introduction to Alain Badiou's Infinite Thought: Truth and the return of philosophy, by Oliver Feltham and Justin Clemens we find this statement:

"When poststructuralists do engage with problem of agency they again meet with difficulties,and again precisely because they merge their theory of the subject with their general ontology. In his middle period Foucault argued that networks of disciplinary power not only reach into the most intimate spaces of the subject, but actually produce what we call subjects. However, Foucault also said that power produces resistance. His problem then became that of accounting for the source of such resistance. If the subject--right down to its most intimate desires, actions and thoughts--is constituted by power, then how can it be the source of independent resistance? For such a point of agency to exist, Foucault needs some space which has not been completely constituted by power, or a complex doctrine on the relationship between resistance and independence. However, he has neither."

One claim here is puzzling. It is that if Foucault claims that power completely produces the subject so as to act in concert with relations of force, then it is not possible for him to also claim that this totalizing power produces resistance on the part of these same subjects.

Is that so?

Why cannot relations of force/power produce (shape) the free subject and resistance by that subject? If you take the power relations of our political institutions, then these shape you so that you become a different kind of person who can also resist the particular use of power in that institution. Power and resistance are fused together. Resistance is not a different sort of thing to power.

June 20, 2005

medicine, snakeoil, politics

I'm back after several days away in Sydney caught up in conference on medicine,health and philosophy. Hence my interest was caught by this conservative defence of modern biomedical medicine (orthodox medicine)and its contribution to our collective well-being.

This passage from the review is instructive:

"Tallis is right to argue that there is a sense of crisis within medicine. But it is not a crisis in the practice of medicine or within the system of our health care. The technical aspects of medical care improve steadily year by year. Instead, the crisis lies within the profession itself. Levels of doctor discontent run high in most countries with advanced high-technology clinical care."

I'm not so sure. There is a pervasive decline in professional self-confidence among doctors associated with a loss in status that doctors have felt in recent years. Doctors are increasingly seen as tradesmen whose income is protected by a very powerful trade union that continually engages in s restrictive trade practices.

However, it strikes me that the modern system of medicine and public health is under a great deal of pressure and is increasingly being placed under question by consumers; consumers who speak the language of rights, want self-control over their health, seek knowledge of their illness and are prepared to question the authority of the benevolent paternal doctor. They are beginning to turn away from orthodox medicine to what manay say is complimentary or alternative medicine.

The conservative response is this:

"....scientific medicine is defined as the set of practices which submit themselves to the ordeal of being tested. Alternative medicine is defined as that set of practices which cannot be tested, refuse to be tested, or consistently fail tests. If a healing technique is demonstrated to have curative properties in properly controlled double-blind trials, it ceases to be alternative. It simply, as Diamond explains, becomes medicine."

Alternative medicine is snakeoil. So says Richard Dawkins.

That does not address the practices of the clinic or the politics of medicine.

June 15, 2005

the poverty of academe

This little op. ed. by James McConvill in the Sydney Morning Herald speaks a lot of truth about academe in Australia. He says:

"As a young academic, I have been frustrated by the resistance to fresh and challenging ideas in my discipline of law. There is a clear and positioned elite who dare not to depart from their conservative views.Many full-time academics in my discipline simply do not publish. When others, like me, attempt to live up to our desired role as genuine intellectuals, we are often criticised or sidelined."

And:

"The role of the critical intellectual must be recognised and respected, rather than being allowed to decline by academics clinging tightly to a culture of mediocrity. If the promotion of ideas does eventually come to play second fiddle to the provision of services in universities, I may as well return to practising law rather than continuing as an academic."

Is this what happens with the emergence of the corporate university?Or is that too crude?

June 14, 2005

Leo Strauss in Australia

The Australian 'Leo Strauss' is the one associated with the activities of his American disciples, many of whom are deeply involved with Republican and neoconservative politics. Hence we have the efforts to trace the Straussian influence in the corridors of power in the current Bush administration.

Such a reading is based on this kind of material. The duality interpretation appears to be the one adopted. On the one hand, Strauss created the hard core of the "esoterics," like the late Allan Bloom, Paul Wolfowitz, Werner Dannhauser, Thomas Pangle, and many others, who share Leo Strauss's secret Nietzschean doctrines, and secretly view themselves as Nietzschean "supermen," or "philosophers."

On the other hand, around this inner group, is the softer outer layer of the "exoterics," like William Bennett, Harry Jaffa, etc who are loyal to Strauss and his sect, but at the same time innocent of Strauss's actual views and committed to versions of traditional morality, patriotism and religion.

Most Australian academics have not read Strauss, nor are they ever likely to, as they have lost connection with the philosophical tradition that Strauss was at home in. Most of the lefty (ALP) academics work in the post-positivist social sciences (economics, sociology and history)and have little understanding of the political philosophical tradition. So they rely on secondary texts with their dubious interpretations, and have no way of evaluating the competing interpretations of Strauss's texts.

Tis guilt by association.

A quote from this review of Anne Norton, Leo Strauss and the Politics of American Empire, gives the flavour. The review argues that the US Straussians aim to create an American empire and to carry out a project of universal dominion. Norton notes that he [Leo Strauss] travelled in the orbit of Martin:

"Heidegger and Carl Schmitt, the twin philosophers of the Third Reich, and that their suspicions---about liberal democracy, the Enlightenment and rootless cosmopolitanism---run throughout his work. Thus it is hard to see the Straussians as anything less than emblematic figures of the American right, which shares far more affinities with the spirit of the European counter-revolution than we might think."

Maybe; in the sense that both were opposed to the modern Lockean doctrine of natural right that is based on possessive self-ownership.

However, unlike the European conservative counter revolution (Heidegger) Strauss grounded his philosophy on classical natural right that rests upon a (Aristotlean) teleological view of nature, i.e., one that states the nature of things is found in their perfections.

A critical review of Norton's text. What we get in Australia is a dismissal of Heidegger and Schmitt because of their politics. It is assumed that their philosophy is so deeply contaminated by their politics that it is fascist and to be attacked.

What we have in Australia is liberalism defending itself from criticisms by gatekeeping that keeps the borders closed and allows no foreign bodies in. Strauss is rejected because he is a conservative critical of liberalism. There is no need to examine the arguments that highlight the flaws of liberalism because it is conservatism that is the problem, not liberalism. So Strauss is rejected because of his politics.

June 13, 2005

between academia and internet gibberish

I've just come across Naked Punch courtesy of a Gauche It addresses the future based on a shift away from the academic journals locked up and inaccessible to those without subscriptions, and the new philosophical writing available on the web that is forming. We are not there yet and more online resources are needed.

The promise of Naked Punch is a good one. The task it has set itself:

"...is to lodge itself in between so called 'high academic' discourse and the dubbed down gibberish of publications we shall not name! All too often it seems impossible to pick up a journal without either being utterly baffled by an obscure argument resting upon an army of footnotes or down right disappointed when faced with yet another 'Science vs. Religion' paper, glossy pictures of bearded men included.Naked Punch pitches it 'just right', walks the middle road: we believe that what readers are looking for are informed, well-written, sometimes entertaining pieces of criticism.

One shouldn't have to siphon through a mass of references or understand Heideggerian jargon to get to the real heart of an article. The radical questioning which does not see theory and practice as divided that impassions us must be as accessible and lucid as possible.

At the same time we are interested in furthering a more overtly theoretical philosophical and political discussion, reason for which some of our articles do sometimes include a few footnotes and a few "technical" terms."

Sounds so good doesn't it. Hits all the right spots. Too good to be true?

Naked Punch mostly works the philosophy and art vein. A selection of articles are online, and there is the odd article on philosophy and politics.

In this selection from an 'Interview with Antonio Negri' Negri says:

"I see our period as a major transitional stage, like a classical interregnum ... I have a feeling that we are living through a phase of transition from the modern into the post-modern, which is itself endowed with a series of very peculiar characteristics. And it is a phase in which a battle is taking place to decide who and how will exercise the power over the empire, over the entirety of the surface of the globe, and to identify and determine the structure of power within a market and a general structure already completed. The most fundamental concept that needs to be grasped is the capitalistic convergence over a common interest in constituting a structure of command, namely a normative structure."

Yes, we are living through a major transitional stage and there is a battle taking place to decide who and how this power over empire will be exercised.

But that does mean we turn away from what is happening inside nation states:

The law does not exhaust the question of an ethical response to the mandatory detention camps and the way they are run. "Why do we need to keep people locked up until they've lost their mind?" ask Jud Moylan.

An ethical confrontation is required: one based on the testimony and witnessing of those who endure a bare life in the camps.

June 12, 2005

Badiou: philosophy and politics

Yesterday afternoon, when I was at the Dark Horsey bookshop at the EAF in Adelaide, I picked up a copy of Alain Badiou's text, Infinite Thought: truth and the return to philosophy.

In it there is a chapter on philosophy and politics, a subject about which there is much confusion, judging by the eternal recycling of the debate on Heidegger and politics that never seems to go anywhere. Much of the noise and chatter created in response to revelations of Heidegger's Nazi involvements avoids the cause of a serious discussion of the contribution philosophy might make either to politics or to the political.

What does Badiou say? He says that the philosopher's concern about politics is about justice. Can there be a just politics? Justice is then linked to truth. He then adds:

"The vast majority of empirical political orientations have nothing to do with truth, We know this. They organize a repulsive mixture of power and opinions. The subjectivity that animates them is that of the tribe and the lobby, of electoral nihilism and the blind confrontation of communities. Philosophy has nothing to say about such politics; for philosophy thinks thought alone, whereas these orientations present themselves explicitly as unthinking, or as non-thought. The only subjective element which is important to such orientations is that of interest."

Well that is a return to Platonism.

There is nothing there about democratic deliberation, argument, democracy, federalism, nation, state, civil society, family biopolitics, the camp--the categories that shape the "non-thinking" of the tribe and lobby as they defend their interest.

I am reminded here of Agamben's thesis that the camp is the 'biopolitical paradigm of the modern'. Even if Agamben's reformulation of the concept of biopolitics is only partially convincing, his thesis of the central political significance of the camp indicates the way that philosophy can work on the terrain of the opinions of everyday political life.

June 11, 2005

Giorgio Agamben: Remnants of Auschwitz

I picked up a copy of Giorgio Agamben's Remnants of Auschwitz yesterday afternoon from the Dark Horsey bookshop at the EAF in Adelaide.

Chapter One is entitled 'The Witness', and it concerns those who survived so that they could bear witness to what happened. We rely on their testimony to think through the meaning of Auschwitz. In this chapter Agamben writes:

"Despite the necessity of the [Nuremberg] trials and despite their evident insufficiency (they involved only a few hundred people), they helped to spread the idea that the problem of Auschwitz had been overcome. The judgement had been passed, the proof of guilt definitively established."

I have to acknowledge that is my position. It is a European problem, if there is an ongoing problem. Australia's problem is the mandatory detention camps, not Auschwitz. That was a unique event. We in Australia have to think through the detention camps.

Agamben questions this position. He continues:

"With the exception of the occassional moments of lucidity, it has taken almost half a century to understand that law did not exhaust the problem, but rather that the very problem was so enormous as to call into question law itself, dragging it to its own ruin."

What we have is a conceptual confusion that, for decades, makes it impossible to think through Auschwitz; a conceptual confusion between law and morality and between theology and law.

When people morally think about the wrongness of Auschwitz they often think in terms of responsibility and guilt. Agamben says that:

"But ethics is the sphere that recognizes neither guilt nor responibility; it is, as Spinoza, knew the doctrine of the happy life. To assume guilt and responsibility---which can, at times, be necessary---is to leave the territory of ethics and enter that of law."

The confusions go deeper than that. Guilt and responsibility evokes Christianity--theology---for me, more so than the law.

Can we say that ethics is limited to the happy or good life. That is the classic conception of ethics. Is there not also the Kantian one, which is concerned with the autonomous person and the moral law? Can we not also say that ethics is concerned with alleviating suffering?

What Agamben is trying to do is delinate an area of ethics of witnessing that is prior to, and before, the legal codification of judgment and responsibility.

June 10, 2005

debating the camps

There is a post by Nicolas Gruen over at Troppo Armadillo that refers to Amnesty International's linking the Soviet Gulag to the American Guantanamo Bay in its Amnesty International Report 2005 in Irene Khan's Foreward. Gruen's post is basically a link to a post by Ted Barlow over at Crooked Timber.

In the foreward Irene Khan says:

"...the US government has gone to great lengths to restrict the application of the Geneva Conventions and to "re-define" torture. It has sought to justify the use of coercive interrogation techniques, the practice of holding "ghost detainees" (people in unacknowledged incommunicado detention) and the "rendering" or handing over of prisoners to third countries known to practise torture. The detention facility at Guantanamo Bay has become the gulag of our times, entrenching the practice of arbitrary and indefinite detention in violation of international law. Trials by military commissions have made a mockery of justice and due process."

Exception was taken to Khan's phrase, "detention facility at Guantanamo Bay has become the gulag of our times", by the New Republic (subscription required) online.

Ted Barlow's post is his open letter to the New Republic.

In it Barlow says:

"In this speech, she [Kahn] made an overheated and historically ignorant comparison of Guantanamo Bay to the Soviet gulags. In response, Bush administration officials joined the ignoble ranks of leaders who have responded to Amnesty International reports of human rights abuses with spin and self-pity."

He says that he understands the objection to the term 'gulag' because the gulags were a vastly larger evil, and a part of a far more sinister and omnipresent system of repression. He critises New Republic for not scrutinizing and criticising the human rights abuses performed in America's name, by the elected government.

Lots of fuss then centres around the use of gulag in the American context. Agamben's use of the camp as a juridico-political category cuts through to the heart this debate. It enables us to link the different kinds of camps--Australia's mandatory detention, the Soviet gulag, the Nazi concentration camps, America's Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib, the British emergency detention camps in 1950s Kenya, or the French detention camps in Algeria--and to think of these in terms of a bare life.

June 9, 2005

rethinking the political space

In 'Threshold', the last chapter of Homo Sacer, Giorgio Agamben makes an interesting comment about returning to the classics to get a critical purchase on modernity. He says that:

"Every attempt to rethink the political space of the West must begin with the clear awareness that we no longer know anything of the classical distinction between zoe and bio, between private life and political existence, between man living at home in the house and man's political existence in the city. That is why the restoration of classical political categories proposed by Leo Strauss and, in a different sense, by Hannah Arendt, can only have a critical sense." (p.187)

There is, in short, no return from the camps to classical politics.

What does the camp mean? It means security. This recalls Hobbes: security from fear is the reason human beings as a people unite in a state. Fear of being swamped by millions of refugees on the move that include terrorists is the reason behind the camps.

Today in Australia, or the US, security has become the basic principle of state activity. With the national security state security becomes a central criterion of political legitimation. The danger here is that a state that has security as its main task and source of legitimacy can always be provoked by terrorists to turn itself terroristic.

June 7, 2005

Agamben: Australian reception#1

I have shown in my commentary below on Giorgio Agamben's difficult Homo Sacer that his work is very relevant to what is happening in Australia with respect to refugees, mandatory detention and the camps. It enables us to talk about the treatment of asylum seekers in a different language to that of human rights.

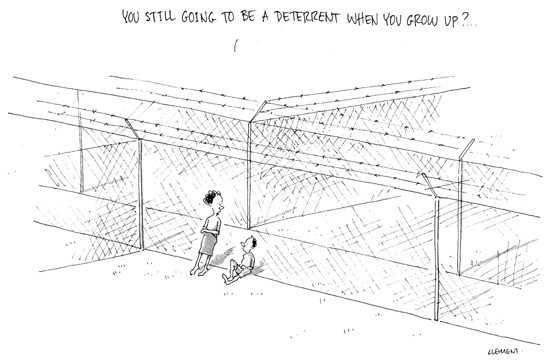

Cathy Wilcox.

The incident referred to in the cartoon is this. Chen Yonglin, a senior diplomat at China's Sydney consulate who was responsible for monitoring dissidents among the Chinese diaspora in NSW, had sought political asylum from Australia, and was rejected.

If we use Agamben's language we would rewrite the caption of the cartoon to say 'take him to the camp' and not 'show him to the asylum'. The camp is the biopolitics space of modernity.

How then is Girogio Agamben received in Australian academia?

Here is one account by Catherine Mills in Borderlands which addresses Agamben's Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive, which I have ordered but not read. This text is a consideration, and rethinking of, ethics in response to the camps--an ethics after Auschwitz based on the testimony of the survivors who bore witness to something unspeakable. Such an ethics is an ethics of witnessing.

Mills reads Agambe's text similarly to myself. She says that despite problems with the way Agamben structures his work, 'Agamben's insights nevertheless disclose and expose the assumptions often too readily accepted in contemporary debates and open a theoretical space for further elaboration.' In that space we find the latest issue of Contretemps devoted to the work of Agamben.I read those texts and found the academic language rather heavy going, without having first read Agamben. Hence my decision to read and work my way through Homo Sacer. I will return to them in latter posts.

An ethics of witnessing is useful as it makes for an opening into a new theoretical space of the political in Australia. Such an ethics has appeared in both the Bringing them Home and A Last Resort? reports by HREOC. The difference that should be noted is the nature of the witness: for Agemben it is not the testimony of the survivors of the Nazi concentration camps, but those who have not returned at all or have returned mute.

Agamben introduces the figure of the Muselmann, which Mills characterises thus:

"...the extreme figures of survival who no longer sustained the sensate characteristics of the living but who were not yet dead. The term 'Muselmann' refers to those in the camps who had reached such a state of physical decrepitude and existential disregard that 'one hesitates to call them living: one hesitates to call their death death'.... 'Muselmann' names the 'living corpses' that moved apparently inexorably toward death in the camps, beings who, through exhaustion and circumstance, had lost the capacity for living. They are the 'anonymous mass' that formed 'the backbone of the camps'"

This is the threshold between human and inhuman, life and death, and it is approached in the detentrion camps in Australia through the effects the camps have on the mental health of those incarcerated.

June 6, 2005

Giorgio Agamben: the camp in modernity

Recently two legal academics--Mirko Bagaric and Julia Clarke--from the law school at Deakin University---stated in The Age that government sanctioned torture was a 'permissable' and 'moral' action in certain circumstances justified on utilitarian grounds. It is a calculation of one tortured terrorist versus an innocent life. Peter Faris, one time head of the now defunct National Crime Authority, supported the case for torture (minimized as pulling out a finger nail) in the context of "the war of terrorism."

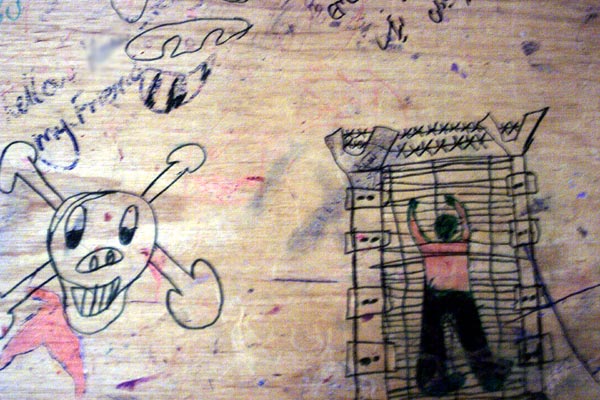

Presumably this government sanctioned torture would take place in the special detention camps within a constitutional liberal democracy:

Clement

We need to pause and take note of what is being proposed here. As Desmond Manderson says in his article, 'Another Modest Proposal' in the Review Section of Friday's Australian Financial Review:

"Torture is used to punish and humiliate dissidents, terrorists and members of ethnic minorities. It is a demonstration of what the state can do to you and its effect is to create a generalised fear about the infinite and random power of the state to destroy lives, and an intense sense of vulnerability in victim populations."

Government action and public law carry a mark of legitimation of cruelty used to enforce state power. That means state sanctioned torture is now on the political agenda.

When you couple this with Australians facing trial before U.S. military tribunals, asylum seekers languishing in camps like Baxter and Nauru, and new government legislation allowing the detention of Australian citizens themselves, then it appears that a fundamental shift has taken place in the political life on the southern continent.

What is the shift?

At this point we can turn to, and take seriously, Giorgio Agamben's argument in Homo Sacer. This argument is succinctly summarized in the concluding chapter of the text entitled 'Threshold.' The argument is organized around three main points:

1. The original political relation is the ban (the state of exception as zone of indistinction between outside and inside, exclusion and inclusion).

2. The fundamental activity of sovereign power is the production of bare life as originary political element and as threshold of articulation between nature and culture, xoe and bios.

3. Today it is not the city but rather the [concentration] camp that is the fundamental biopolitical paradigm of the West. (p. 181)

The kick is in the last bit. The concentration camp is the paradigm of modernity. It is the camp that is politically significant.

What is disturbing here is the failure of a liberal critique of the camp in Australia that those in detention suffered numerous and repeated breaches of their human rights. Australia's detention of children, HREOC says, has been "cruel, inhumane and degrading." The critique softens the harsh edges--children should not be in detention camps---but thre is an acceptance of the necessity of the camps. The merits or value of the camp as a tool of migration management is not, and cannot, be put into question. The camp is accepted as a legitimate and stable expression of state power and sovereignty.

Consider the gap between the rhetoric and reality around the camps. The contract between the Australian Commonwealth and GLS Solutions, the detention 'services provider', notes that:

"The Government takes its responsibilities for the care of all people in immigration detention seriously and expects its Services Provider to do likewise… Emphasis is placed on the sensitive treatment of the detention population which may include torture and trauma sufferers, family groups, children and unaccompanied minors, the elderly, persons with a fear of authority and persons who are seeking to engage Australia's protection obligations under the Refugee Convention." (DIMIA, 2003: Part 1, Para. 6)

Is there not an incongruity of sensitively protecting individuals incarcerated in a camp in and through an instrument of ostensible persecution?

What this indicates is that the protection of detainees in the camps is considered secondary to the greater responsibility of the state protecting citizenry and community from undesirable groups. This protection requires containing what causes anxiety to prevent the undesirables from absconding. This protection necessitates vigilance by the state. So says the liberal constitutional state.

It is the camp that should be placed into question.

June 5, 2005

Agamben: the camps in political life

In the second to last chapter of his innovative Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life the Italian philosopher, Giorgio Agamben, deals with the significance of the camps in political life. Agamben states his thesis bluntly. He regards the camp:

"... not as a historical fact and an anomaly belonging to the past (even if still verifiable) but in some way as the hidden matrix and nomos of the political space in which we are living."

The camp as a space of exception is more than a piece of land placed outside the normal juridical order. It is the site or structure in which the state of exception (whereby sovereign power decides a mode of life is to be actively and continuously excluded or shut out of political life) is realized normally.

It is in the camp where human beings are reduced to bare life (a life exposed to death) and which marks the exclusion of this mode of life from the polity as a distinctively human life.

We in Australia see the camp as belonging to history---to the fascist state in Germany or the gulag in the Soviet communist state. Though we Australian citizens see the mandatory detention centres as refugee camps, we do not link these back to the camps of the past. These camps stand on their own, isolated in a political vacuum.

We understand that Australian law requires the detention of all non-citizens who are in Australia without a valid visa (unlawful non-citizens). This juridico-political category means that immigration officials have no choice but to detain persons who arrive without a visa (unauthorised arrivals), or persons who arrive with a visa and subsequently become unlawful because their visa has expired or been cancelled (authorised arrivals). Australian law makes no distinction between the detention of adults and children.

Mandatory detention in Australia, means that when children arrive in Australia without a visa and are seeking asylum, they are required to stay in detention well beyond the period of time it takes to gather basic information about an asylum claim, health, identity or security issues. Both adults and children must stay in detention until their asylum claim has been finalised or a bridging visa has been issued.

The consequence is that children are often detained for months and sometimes for years, many of them in detention centres in remote areas of Australia. We see the refugee camps as anomalies that blight our polity and which bring shame to the Australian nation-state.

Agamben challenges this by arguing that the camp is the very paradigm of the political space at the point where politiics becomes biopolitics and hom sacer (one banned from society and all rights as a citizen are revoked) is virtually confused with the citizen. He says:

The correct question to pose concerning the horrors committed in the camps is...not the hypothetical one of how crimes of such atrocity could be committed against human beings.It would be more honest and ... more useful to investigate carefully the juridical procedures and deployments of power by which human beings could be so completely deprived of their rights.

The camp is the permanent space of exception of the politics that we are now living. It is the space where everything is possible.

What has shifted can be seen in terms of the bare life, understood in the sense of being included in the political realm precisely by virtue of being excluded. Once abandoned by the law at the outskirts of the polis, bare life today, argues Agamben, has fully entered the polity in liberal constitutional states in the form of the camp, to the point of rendering outside and inside, life and law, truly indistinguishable from one another.What Agamben is arguing, say Nassser Hussain and Melissa Ptacek in Law and Society Review(2000) is a general thesis:

"...that biological life in the form of bare life has become the object of politics in the modern world and that, perhaps more provocatively, the political realm constituted by sovereignty has as its originary-and thus continuous-aim the very production of this bare life..."

The birth of the camp signals the political space of modernity. To the modernity's trinity of state, nation and territory we can add the camp.

June 2, 2005

Giorgio Agamben: the homo sacer project

As I continue to work my way through Agamben's Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life I'm begining to understand that the figure of homo sacer can be seen as an ongoing project for Agamben. This paragraph from this background text on Wikpedia captures the dimensions of the project well:

"Since its origins, Agamben notes, law has had the power of defining what "pure life" is by making this exclusive operation, while at the same time gaining power over it by making it the subject of political control. The power of law to actively separate "political" beings (citizens) from "pure life" (bodies) has carried on from antiquity to modernity - from, literally, Aristotle to Auschwitz. In a daring but plausible move Agamben connects Greek political philosophy to the concentration camps of 20th century fascism, and even further, to detainment camps in the likes of Guantanamo Bay or Bari/Italy, where asylum seekers have been imprisoned in football stadiums. In these kinds of camps, entire zones of exception are being formed. Sovereign law makes it possible to create entire areas in which the application of the law itself is held suspended."

What we have with this project is an anlytic of concepts that form paradigm or historical structure.

Agamben states it thus:

"I am not an historian. I work with paradigms. A paradigm is something like an example, an exemplar, a historically singular phenomenon. As it was with the panopticon for Foucault, so is the Homo Sacer or the Muselmann or the state of exception for me. And then I use this paradigm to construct a large group of phenomena and in order to understand an historical structure, again analogous with Foucault, who developed his "panopticism" from the panopticon. But this kind of analysis should not be confused with a sociological investigation."

According to ancient Roman law, Homo Sacer is a human being that could not be ritually sacrificed but whom one could kill without being guilty of committing murder. Agamben's dileneation of the historical structure of this figure in politics and law enables us to use the concept to decode one the major political issues in our century: the rise of the detention camps in liberal democratic societies, such as America's detention camp at Guantanamo Bay and the mandory detention camps for asylum seekers in Australia.

June 1, 2005

homo sacer: a life unworthy of being lived

I'd read some more of Giorgio Agamben's interesting Homo Sacer as I flew to and fro from Canberra yesterday. I'm finding the book a bit of a struggle, but it's genealogical account of homo sacer coupled to its use of Schmitt, Arendt, Foucault is dealing with a central problem in political life.

As we have seen Agamaben argues that the figure of homo sacer, classically seen as able to be killed but not sacrificed, is the figure of a person who has committed a certain kind of crime is banned from society and all of his rights as a citizen are revoked.To a homo sacer, Roman law no longer applied, although he was still "under the spell" of law. Homo sacer was excluded from law itself, while being included at the same time. This figure is the mirror image of the sovereign (a king, emperor, or president) who stands, on the one hand, within law (so he can be condemned, e.g. for treason, as a natural person) and outside of the law (since as a body politic he has power to suspend law for an indefinite time).

The figure of hom sacer becomes a life unworthy of being lived in modernity. That is the life of a stateless person in Australia's detention camps, and so homo sacer becomes a juridico-political concept linked to sovereignty.

Agamben links this to the sovereignity (sovereign is he who decides on what constitutes the state of exception)--which was deployed and defined as the arrival of the refugee boat people and the Tampa incident in 2001. Agamben says:

"If it is the sovereign who, insofar as he decides on the state of exception, has the power to decide which life may be killed without the commission of homicide, in the age of biopolitics this power becomes emancipated from the state of exception and transformed into the power to decide the point at which life ceasess to be politcally relevant. When life becomes the supreme political value, not only is the problem of life's non-value thereby posed, as Schmitt suggests but further, it is as if the ultimate ground of sovereign power were at stake in this decision."

This leads to a transformation in Carl Schmitt's definition of sovereignty as he who decides on what constitutes the state of exception:

"In modern biopolitics, sovereign is he who decides on the value or nonvalue of life as such. Life--which, with the declaration of rights, had as such been invested with the principle of sovereignty --now itself becomes the place of sovereign decision."

This places asylum seekers, refugees, and mandatory detention at the centre of political life. You can see why I continue to struggle with Agamben's texts.