July 31, 2005

Are we not witnessing a turning away from public life that arises from a disillusionment with political leadership and political institutions accompanied by retreat into privacy? A retreat into the trails and joys of the self-regulating market and consumer society?

Does that not mean a rejection of the political as a determinate public space (a forum, an agora)? Does it not mean that the political has been invaded by the market?

July 29, 2005

'us' versus 'them'

When framed by the rhetoric of the war on terror democracy is seen as under threat and our 'way of life needs to be protected from 'them' who hates 'us' and what 'we' stand for. Any dissension or criticism of this division marks one as un-Australian and against 'us', democracy and 'our way of life.'

Jane Mummery argues that in this context there is a need for the commonality of democracy in a liberal nation-state to be informed by pluralism, dissension and undecidability.

She turns to Chanatal Mouffe to help her think through the questioning of the 'us' versus 'them' logic:

"Mouffe argues that 'the belief that a final resolution of conflicts is eventually possible is something that puts [democracy] at risk. For Mouffe (as it also is for Derrida), the democratic project is constitutively agonistic and pluralist. It marks and sustains the practice of contestation rather than any substantive consensual notion of the common good or even a 'we'... As a plurality, Mouffe insists, democracy is necessarily agonistic, insofar as the sustaining of difference is the sustaining of dissension...what this means is that the crucial problem in democratic politics for Mouffe is... the establishing of these democratic equivalences in a process she sees as the transformation of antagonism into agonism...Mouffe argues that every truly democratic community requires that both pluralism and its character of conflict are recognised as constitutive of the public sphere."

The democratic project certainly does not have a clear-cut identity or community. It doesn't need to have. Mouffe is careful to not set any specific identity to this 'we', given that it is constantly under negotiation.

One presumes that Mouffe's conception of democracy, as the agonistic plurality of determinate democratic struggle that undermines the 'us' versus 'them' logic is enframed by particular existing institutions, practices and values of liberal democracy.

July 28, 2005

rethinking republicanism

I've always found the Australian conception of Republicanism strange. 'The republic' had been characterised as separation from the British monarchy, and an Australian head of state.

Republicanism in Australia has not been articulated in terms of a republican political philosophy, which holds that a system of self-government is based on active and public-spirited citizenship requiring participation in political life.

Should not the Australian republic be conceived in positive terms as a reform of our political system to enhance our commitment to the empowerment of citizens?

July 27, 2005

rights as capabilites

Natural law philosophers (such as Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, and Kant) used the term civil society as an antonym for natural society. In "natural society" each person had only the rights they could defend for themselves. The Lockean conception of natural right of the abstract individual holds that they are claims that individuals have on other individual's non-interference with my enlightened self-interest.

This emphasis on natural right does not specify the good and it assumes the myth of natural society. A better conception of civil society is the Hegelian one of non-state society between the family and the state which brings individuals into relationships of cooperation with others on the basis of their own inclinations or desires to work and live.

One way to avoid abstract right is to view rights as capabilities: we argue for rights on the basis of their ability to provide the conditions in which people can construct and pursue meaningful lives. This is a more diffuse concept of rights, that I think intentionally avoids reduction to a list of particular measures. Combined with deliberative democracy, the capabilities' approach takes on the character of a theory of democratic participation.

Thinking of individual rights as capacities to participate in democratic deliberation solves any perceived tension between negative rights and positive rights. There is no practical sense in which individuals can have freedom from non-interference without having correlative freedoms to achieve freedom self-determination So-called negative rights, rights against the state, are of course necessary guarantees of personal freedom from arbitrary power. However, any privileging of these rights over the positive rights of individuals of self-determination ignores the way that inequality and discrimination subvert the effective functioning of civil society and associational life.

July 26, 2005

Natural right & historicism

Leo Strauss's response to the crisis of modernity, the view that 20th century relativism, scientism, historicism, and nihilism have been responsible for the deterioration of modern liberal society, and philosophy, is natural right. Natural right blocks the historicist move that leads to relativism and nihilism as it provides a firm foundation in reality for the distinction between right and wrong.

Strauss's project was to recover nature as the foundation for all our morality and so block postmodern nihilism and the historicism of the post-Hegelians historicists, who deny that reason can discover unchanging principles of right and wrong. The big struggle between natural right and historicism is at the core of modernity, and you can interpret Strauss's texts to argue that this conflict lay at the heart of the founding of the American republic. That event was founded on natural rights, and the Founders believed in their revealed religion as grounding natural law.

Natural Right and History explores this terrain by re-reading the classic texts in political philosophy to show that the reasons which have led to a rejection of natural right are not good ones. Strauss is engaged in revitalizing the potential of political philosophy, which had been buried by positivism in the social sciences and historicism in philosophy.

In this text Leo Strauss deploys his ancient-verses-modern dichotomy to highlight the distinction between classical and modern natural right. We usually understand the ancient modern difference in terms of the classical view that "human beings are by nature a social being" or political animal, and the moderns who held that the individual is prior to society. Strauss maintains that the classical understanding of political things is decisively superior to the modern one.

Classical natural right claims the good life for man to be "the life that is in accordance with the natural order of man's being, the life that flows from a well-ordered or healthy soul . . . The perfection of man's nature." However, beginning with Hobbes, modern natural right finds the possibility of man's perfection wholly impractical, instead championing the instinct of self-preservation and the rights of the individual.

Instead of reading Strauss's duality as ancients good, moderns bad,we can explore their presupposition to gain an understanding of modernity. The ancients in one way or another conceived of nature as a restraining order within which human beings lived out lives of lesser or greater virtue; the moderns saw nature as an alien other to be overcome through human activity. The distinction between the ancients and the moderns lies in determining which is the central grounding principle for moral and political life--nature's order, or humanity's will.

What Strauss makes apparent is the necessity of the opposition between the ancients and the moderns, between natural law and natural right, between natural order and human freedom. So at the root of modernity is the view that there is nothing independent of humanity which is superior in dignity to human artifice; the design of politics is rooted in human freedom and not divine or natural necessity.

Locke, for instance, was interpreted by Strauss as rejection of virtue as a concern of government. Locke, according to Strauss, turned to acquisitiveness as a substitute for virtue. Does that mean that constitutionalism needs a stronger foundation than the Lockean doctrine of natural rights based on self-interest?

Hence the importance of Strauss's interpretation of the American constitution. On this interpretation, The Declaration of Indepedence marked an understanding, on the part of the American Founders, that connected them to the classics, to the classical understanding of natural right and to the biblical tradition. That means a doctrine of natural rights under natural law.

July 25, 2005

an odd silence

Consider this quote from the Introduction of Alan McKee's The Public Sphere, which I bought today when I dropped into Imprints after a meeting in the city:

"It's only in the mass media that vast populations of people can come together to exhange ideas. You can't fit the entire population of America, or Britain, or Australia into a townhall where they could all discuss issues that affect them. The media is the place where we find out about 'the public' the millions of other people that we share a country with."

Oh? Do people actually come together in the corporate media to exhange ideas? That makes little sense at all in Adelaide, given the lapdog print media is on the state government's drip feed, and most articles recycle the media releases.

Talk back radio is a coming together.

For a text that is written in 2005 that is a strange silence about the internet in relation to the public sphere.

Now McKee does qualify this statement:

"The 'public sphere' isn't exactly the same as thing as 'the media'. But these terms are used interchangeable in two different situations---academic discussions and popular writing respectively."

However, there is still a silence about the internet as extending the boundaries of the public sphere.

Update: 26 July 2005

I have found further qualifications in the middle of the book:

"The Internet has changed the nature of the public sphere in Western democracies. It's revitalized traditional grass roots politic as involvement ...But more important than this, it's become a part of an important rethinking of what actually constitutes politics. The emerging 'anti-globalization ' movement brings together the medium of the Internet with a primarily young demographic, and a rethinking of the nature of activism--through 'cultural jamming'---to create a new vision of politics. Cultural jamming attempts to change the way that people think about the world by playing with existing culture, and thus introducing new ideas into the public sphere...Cultural jamming has reached its potential due to the technology of the Internet..." (pp.172-3)

That conception of cultural change---changing the way events are represented by the corporate media--- effectively undercuts the identity of public sphere and media established in the introduction.

July 24, 2005

'Protecting Australia Against Terrorism'

In the wake of the London bombings the current hegemonic discourse of terrorism with its duality of us as good/civilised/rational and the Other as evil/uncivilised/irrational has become easily embedded in Australia's internal experience of security.

I'm not just thinking of the displacement of asylum seekers out of a discourse from humanitarian or ethical or even international legal discourse into one of 'threat' and 'security', that defines asylum seekers as undermining Australia's sovereignty, violating its borders and so needing to be deterred and repulsed.

Nor am I thinking about the constant reminders that we Australians We are now directly threatened by a new kind of terrorism', with its recourse to fear and anxiety throughconstant reminders to us that we are not safe in the new globalised security environment after 9/11.

I'm thinking about the way the One Nation conservative media critics of multiculturalism are at it again: equating multiculturalism with ghetto's; seeing ghettos as the breeding grounds that allow homegrown terrorists to flourish; and running the sick culture of liberalism is to blame line.

Assmilation--not cultural diversity--is the conservative response, given their presupposition of the clash of civilizations, their legitimation of Australia as a defensive fortress, their rhetoric of are you with us or against us.

As Australian Muslims are deemed to be a threat to the national security state, so violence against them is warranted. Why? Because they exist outside our moral community with its Judaic/Christian tradition, and, as the Other, are therefore not entitled to access our political space or our political values.

July 23, 2005

modernism in politics

Let me make a stab at something. A modernist in politics would work within the Enlightenment tradition, and so presuppose an independent moral/political subject that is capable of constructing and justifying ethics and politics from a standpoint that is outside of all social roles and historical traditions.

They would also want to distinquish truth from power, authority from domination, justicer from hegemony and to preserve an objective trans-pluralistic standpoint from which to judge theory and practice.

Thus modernism in politics has its source and roots in the Enlightenment's political vision of achieving liberation from our self-imposed immaturity (to put in Kantian terms), of attaining social progress and jsutice by means of rational inquiry, public communication and the fostering of moral responsibility.

July 21, 2005

Revisiting Arendt

Those who protest mandatory detention and the internment camps usually do so from the basis of human rights. It is presupposed that modernity is not synonymous with the entrenchment of subjective rights and popular sovereignty. It is characterised by the circular, reciprocal conditioning of subjective rights and democratic procedures of law-making relying on the sovereignty of the people.

Maybe it is time to revisit the work of Hannah Arendt. She explicitly makes the "internment camp" a central figure of modern times. In her classic The Origins of Totalitarianism, (1951) which characterised totalitarianism as an organizational form characterised by centralized control by an autocratic leader or hierarchy, she addressed the issue of human rights. She says:

"The conception of human rights, based upon the assumed existence of a human being as such, broke down at the very moment when those who professed to believe in it were for the first time confronted with people who had indeed lost all other qualities and specific relationships--except that they were still human. The world found nothing sacred in the abstract nakedness of the human being."(p.299)

Only when rights are realised in a political "commonwealth" do human rights have any meaning. They are an abstraction otherwise. More important than the abstract right to freedom or the right to justice is "the right" to be the member of a political community, namely to be a citizen. Arendt's point is that when man and citizen come apart, we realise that man never really existed as a subject of rights.

If you dump universal human rights of the abstract human being, then how do you criticize the imprisonment of Australian citizens in detention/internment camps?

July 20, 2005

speech, blogging and digital democracy

In a response to an earlier post on digital democracy Cameron Riley, over at South Seas Republic, says that:

"...the decentralised data networks will flatten the present political system of status entirely, making us all equal, and wiser for it, [and that] the present politicians, who enjoy their ability to spray bias at a passive audience from the pinnacle of Australian power will have to be brought kicking and screaming into the new decentralised democratic era."

Spray bias? Politicians grant there are a diversity of opinions in a liberal democracy, often say they don't agree with with the views of their opponents or critics, and that the latter are entitled to to their views. They often avoid debate and/or close down the issue.

Not that the bloggers are much better. Matt over at Pau au dela, responding to this excellent post, by Waggish on blogs as a genre of writing says:

"But the impression persists, and it is a dangerous one: blogs are written only for other bloggers, which also means primarily white, relatively well-off, vaguely resentful, and with too much time on your hands. Well surely that's an impression worth disproving."

Things look grim, if we accept, as I do, Hannah Arendt's argument that debate is the core of political life. By this is meant that it is only through the exchange, modification, and criticism of opinion that political deliberation proceeds.

Arendt says that for deliberation in the public sphere to take place there must be certain preconditions: a genuine plurality, equality, commonality and ability.

Do these preconditions apply in the blogging world? There is a plurality of opinion and a diversity of perspectives; the deliberation takes place amongst peers as bloggers as citizens recognize one another on equal footing; the deliberative speech is anchored in a shared world as the debate and disagreements concerning the direction of collective action presumes a certain minimium agreement in background judgements and practices;and ability as bloggers are capable of making judgements, have a commitment to the public thing, and the virtues specific to politics (eg., courage or integrity) that contribute directly to to the vitality and freedom of the political community.

There are some possibilities there, don't you think, in terms of bloggers fostering a public conversation about political matters? They are well positioned to do this. Their ethos is one of articulating and protecting the public realm, and so their speech is genuinely political. It is about promoting a certain way of acting--endless public debate and disagreement---and the values embodied in it---commitment to a particular public world, preserving the fundamental phenomenon of plurality, and fostering the health of the public sphere.

Does not this free the value of the plural realm of opinion from the instrumental modes of action in both the marketplace and 'getting the numbers' kind of party politics.

July 19, 2005

understanding Empire #2

I'm picking up on this earlier post because it never really delinerated what was meant by empire, as this was understood by the Washington neo-cons. We had got to the point in the argument where it was held that U.S. power should serve global capitalism, not the reverse. I'm sympathetic to that line of argument and think that it is worth exploring further.

I'm doing this by turning to Don Hammerquist's response to an angry Stan Goff to help me develop this empire=global capitalism line of argument further. I want to see how far Hammerquist gets in helping us to understand empire. At the moment all we have is empire is global capitalism, as that is understood in terms of political economy.

We can pick up on Hammerquist where he is talking about taking the Washington neo-cons seriously. He says:

'...the neocons have many arguments that they can and do state---along with a few that they usually don't. Their publicly advanced positions on the aggressive use of military power ("preemption"), on "nation-building," and on the significance of "transnational threats" and "non-state actors," have contributed to important changes in policies and priorities for the global and national ruling class...The neocons were confronted with a problem. The strategic course they thought was essential promised to be costly and massively unpopular. So they built a case for it that had no necessary connection with the facts and the truth. Certainly they would be happier if the war and occupation were going more smoothly, but we can expect that they will find ways to make use of the difficulties incurred in Iraq to expedite their general strategy. For them, Iraq is only a first step, an episode, a place to begin---and they have begun.'

Okay. That makes sense. They have to have identified big probles togo to war in the Middle East. So what was the problem the neocons confronted?

Hammerquist addresses this by pointing out the high risks the neo cons are playing with:

'The fact is that neocon policies may well jeopardize economic and political stability in the metropolis. They are willing to risk, not only popular living and working conditions in the imperial center, but also the relative power and influence of the specifically U.S. sections of capitalism. This is why it is so problematic to identify neocon strategy with a resurgence of U.S. imperialism. They would risk the "very basis of American global power" to protect and advance what they call "freedom." There are not many audiences in this country that are receptive to this message, not even in the ruling class.'

Okay. Let us grant that. If the neo-con strategy is not a resurgence of US imperialism (old style), then what is it? What is the problem it is addressing?

Hammerquist then asks the right question: "What perceived dangers lead the neocons to such a risk-laden course?"

Hammerquist answers thus:

'I believe that all factions of the global ruling class and almost every existing national state see salafi jihadism, particularly its takfiri strand, as the current "main danger." ...I think there is clear evidence of a consensus on this point, although it is one that has been reached very recently. This consensus is embodied in the general ruling class acceptance of the so-called "war on terror." Notwithstanding the fact that many of its elements might eventually have a broader usefulness, the political/military core of the war on terror is capitalism's response to the jihadist threat.'

What is the threat the jihadist's pose to global capitalism? What is sort of threat could that be, given the response of a "war on terror"? How does Islamic radicalism actually challenge the economic system of global capitalism? Has not a triumphant global capitalist system been able to defeat or absorb its main challengers?So why is capitalism's response, given that european capitalism rejected that military response.

Suprisingly, Hammerquist's answer is given in terms of fascism:

"Fascism grows out of a dual crisis, a crisis of the capitalist order and a crisis of the movements against that order. Our political reality is dominated by two shaken faiths and two failed gods. First, ...the faith that capitalism is the essential structure of modern progress isn't selling well in much of the world. [So is]... the faith that a fundamental emancipatory alternative to capitalism is both necessary and possible and, indeed, is already well under construction. Capitalism will pay a price for the first failure. We will be paying for the second and the reemergence of fascism will be a part of the price in both cases. We had better expect a fascism that won’t fit in the old definitions...it will be a neo-fascism that grows out of and is decisively marked by the social consequences of the new failures of the revolutionary movement."

If Islamic radicalism is the most advanced outpost of neo-fascist politics in an organizational sense of an animating ideology linking with a mass base at a weak spot in the global capitalist structure, then how does the fascism new style (a postmodern fascism?)---Islamic radicalism----challenge the economic system of global capitalism? And how do the neo-cons understand this challenge?

Saying fascism new style does not give us the answer. I do not see how bombs in Bali and London, or the war in Iraq or Afghanistan, challenge the structure of global capitalism. Hammerquist says:

"The radical transnational Islamic movements are based geographically and politically in the "gaps" in global capitalist system. The most important of these movements are popular----I would say in spite of their authoritarian clandestine structure and reactionary social program rather than because of it. They have a political trajectory that increasingly challenges the rules and norms of global capitalism. The neocons, and some other ruling class factions as well, see this as a movement that could overthrow both compradore regimes in Saudi Arabia and Jordan and rotten neocolonial state structures in Egypt and Algeria. They see movements that might gain control of vital resources, intending, not just to redivide the profits but also to withdraw the resources from the global capitalist system. Finally, they see movements capable of moving beyond the Middle East to northern Africa, and Asia, and, through emigration, to Europe.This is a multi-sided danger to the global capitalist system."

I guess that is a reasonable account how the Washington neo-cons understand the threat to the global economic system. The more cautious voices in the Bush Adminstration have been pushed to one side.

July 18, 2005

Conservative discourse on Palmer Report

The conservative response to the Palmer Report, in erasing any political responsibility for the injustices suffered by Cornelia Ray, downplays the existence, and nature, of the camps in the mandatory detention of asylum seekers in Australia.

Consider P.P. McGuinness, editor of the conservative magazine Quadrant, in his op. ed. in The Australian. He acknowledges that something has indeed gone wrong:

"In the Rau and Alvarez cases there has also been clear incompetence and cover-up by low or medium-level officials of mistakes that are not justifiable. In the Rau case it was obviously difficult to know that a disturbed individual deliberately lying about her name, speaking a foreign language and making no claim to Australian residency rights was in fact a resident, but there is no doubt that she was treated incompetently by DIMIA and other agencies, and without regard to her obvious illness. DIMIA's behaviour with regard to Alvarez seems to have been worse: it seems the officials involved knew early on that there had been an error, but this was not communicated to sufficiently high authority to have it corrected."

Incompetence and error is the theme. It is similar to the PM's line of a few mistakes having made by a good department. That closes off the political responsibility for the culture of denial and self-justification at DIMA.

McGuinness goes on:

"Neither of these cases is evidence of anything other than low-level incompetence - itself a serious enough matter, but not a matter of government policy."

Low level administrative incompetence? More than that is going on. As Andrew Bartlett observes:

"The Palmer Report was based predominantly on just one case, yet there are many many more examples of gross injustices perpetrated by DIMIA. I could list over 100 cases I am personally familiar with over the last few years that have involved huge suffering, major injustices, massive inefficiency, pigheaded inflexibility or what appeared to arbitrary factors determining decisions. Many of these have not been asylum seeker cases; many have involved Australian citizens or families. Some have been hard cases; some seemed to be the result of nothing but bureaucratic pettiness. But I have no doubt that every single one of them occurred in part because the law, backed up in a big way by Government policy and regular Ministerial statements, reinforced the notion that this was how our migration system is meant to operate."Palmer talks about departmental attitudes being promoted by by a culture in which the detention of suspected unlawful non-citizens is the paramount consideration of the policy towards asylum seekers? Is that detention not a key plank in government policy and ministerial direction?

McGuinness, realizing that DIMA's brutish culture and practices are just too bad to ignore, says that:

"There is always room for better treatment of those detained under the terms of a policy on immigration which demands that entrants should be screened in advance. Their detention is often more a matter of the bad advice they are given by lawyers, propagandists and moralists who have no compunction in using these people to serve their own purposes. The bad conditions of their detention, when they are not sheer invention, are difficult to correct when few will address themselves to the amelioration of the conditions rather than a radical and unacceptable, indeed impossible, change in policy."

'Bad conditions','amelioration of the conditions' 'sheer invention' represent a gloss over camps, barbed wire, high detention, solitary confinement, mental illness, 200 cases under review etc. etc. These signify a governance strategy of to transform the human into a non-human by producing the bare life of the camps. That is what erased by McGuinness.

True, McGuinness does recognize that there is a political debate about mandatory detention, detention centres and the treatment of detaineesin Australia. He says:

"The pity of the political debate about...[these issues]... is that it is a political debate: it is dominated by hatred of the Howard Government, hysterical point-scoring and pharisaical posturing. The result is that there is little prospect of any rational discussion about how to improve the humanitarian shortcomings that inevitably creep into any such administrative system, and which in the case of DIMIA seem to have had a corrupting effect on the behaviour of low-level officials."

The words 'hatred', 'hysterical point-scoring' and 'pharisaical posturing' is cartoon politics. It refuses to acknowledge that the Australian Courts have consistently rejected DIMA'S 'reasonably suspect' that the person is unlawfully in Australia. The Court's judgement is that the law states that if the department is hold anyone in immigration detention for any length of time, them the department must know they are unlawfully in Australia. There is a big legal difference between 'reasonably suspect' and 'know.'

DIMA is breaking the law and placing itself out the constitutional order. This indicates that the Howard Government does not respect the rule of law of a constitutional liberal polity.

July 16, 2005

publicness and speech in political life

Andrew Gibson's 'Liberalism and Utopian Publics' published in Agora deals with a key category of liberal democracy--the 'public.' How do we understand the public in a digital world? It is presupposed in a digital democracy with the conversation across and between weblogs?

Is it a realm that can still be contrasted with the private realm of the household? Is a realm that is a key part of the political life of the nation-state; a political life where we develop our human potential for reasoned speech and sense of justice?

Gibson says that a public is:

" an associational form that has become increasingly important throughout the modern period in economic, political, and cultural forms of affiliation, though it is still poorly understood. It is a flexible type of social association ideally premised on discursive openness among indefinite strangers."

A public in political life is a social association that presupposes deliberation and conversation since debate with others is a core aspect of political life. It provides the basis for a nonviolent, noncoercive form of being and acting together. Speech represents the difference between commanding and persuading and political speech (debate and deliberation) between citizens has an end in the making of a decision about which particular course of action is to be adopted.

Gibson goes to say more about the ontology of 'public'. He says:

'The constitution of the political public sphere implied the creation of a public with a greatly extended geographic range, incorporating the disparate discourses of indefinite strangers. What is concealed within this complexity is that "the" public of the public sphere was itself composed of multiple miniature publics, that is, mediated spaces of a lesser scale, which have a tighter discursive consistency, closer to the model of corporeal conversation. "Public opinion" in the singular sense is the imaginary summary point of the multiple discussion spaces it knits together in space and time, such as with the combination of a city newspaper circuit, a national radio station and a neighbourhood tavern.'

He develops two aspects of this. The first is the unity of a public:

"For a public to function, that is, for it to cohere and form a social entity that it makes sense to address, instead of remaining at the level of disjointed bits of discourse, participants have to imagine that their own discourse is an integral part of a larger conversation with indefinite strangers."

This is what we do as citizens. Even though we are strangers, we presume that we are engaged in, and a part of, a national conversation about a particular issue: mandatory detention or industrial relations reform.

Gibson says that rhe second aspect of public is public as a social entity:

'To say that a public--such as the public of the nation, of an interest group, or artistic affiliation--is a social entity means that it forms an interpretative world with its own use of language, its own normative assumptions, and sense of active belonging....The various uses of language it draws on are constituted through particular media, ranging from face-to-face conversation and artistic corporeality to print and electronic discourse. In another sense, language-use has to do with the normative horizons and structures of stranger-relationality that are implicit to preferred genres and vocabularies. These substantive horizons derive their orientation from interpretations of the ethical questions common to all cultural forms, questions of what is important and possible, or, similarly, as Warner notes, of "what can be said and about what goes without saying."'

We citizens in Australia presuppose our own interpretative political world with its shared meanings, assumptions, and ethical concerns, which is different from that of the US or Indonesia. Hence the idea of horizons, which they may overlap are still horizons.

Alas Gibson says nothing about the speech of the public in political life.

July 15, 2005

Hegel: Intro to Phenomenology of Spirit

This post is crossed post to philosophical conversations. The way I'm going to read Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit is in terms of a conversation with J.M Bernstein's 1994 seminar on The Phenomenology of Spirit. The idea of 'conversation' means that my reading Hegel's Phenomenology bit by bit in relation to Bernstein's very interesting seminar is more appropriately done on philosophical conversations.

In the note to the lecture on the Introduction Bernstein says that Hegel was fighting against the instrumentalization of reason that was resulting from the natural sciences-humanities split. That interpretation accords with my reading here. You can see the roots of Adorno and Horkheimer's Dialectic of Enlightenment right there in Hegel.

I'm listening to the seminar now. It jumps in straight away and we pick it up already going. The lecture is talking about the historical formation of consciousness that downplays individual intention, and highlights us as passionate, desiring creatures in history seeking satisfaction.

How does this happen? Hegel says:

"...because this exposition has for its object only phenomenal knowledge, the exposition itself seems not to be science, free, self-moving in the shape proper to itself, but may, from this point of view, be taken as the pathway of the natural consciousness which is pressing forward to true knowledge. Or it can be regarded as the path of the soul, which is traversing the series of its own forms of embodiment, like stages appointed for it by its own nature, that it may possess the clearness of spiritual life when, through the complete experience of its own self, it arrives at the knowledge of what it is in itself." (para.77)

Forms of embodiment can be interpreted as a particular, bounded world of meaning based on our practices. Bernstein uses the mundane, but insightful example of the way we wash the dishes in this particular household. When this is challenged by a guest asking why do you do X, we then realize that it--a form of life--is a particular habitual way of doing things.

The authority for this particular form of life is given by us, as subjects. So it can be changed for a new way of doing things with its particular understandings--- or forms of conciousness/embodiment---by us. Thsi is what we do all the time, right?

Hegel then remarks on the way to understand this having a world or form of life.In para 78 he says:

"Natural consciousness will prove itself to be only knowledge in principle or not real knowledge. Since, however, it immediately takes itself to be the real and genuine knowledge, this pathway has a negative significance for it; what is a realization of the notion of knowledge means for it rather the ruin and overthrow of itself; for on this road it loses its own truth. Because of that, the road can be looked on as the path of doubt, or more properly a highway of despair."

We don't have to do the housework this way at all. It was just our convention.This is a different kind of knowing to that of natural science. It is everyday knowing based on an ordering of the world so that it makes sense to us and the object is under our control.

The story that is told by Hegel is this:

<

em>"For what happens there is not what is usually understood by doubting, a jostling against this or that supposed truth, the outcome of which is again a disappearance in due course of the doubt and a return to the former truth, so that at the end the matter is taken as it was before. On the contrary, that pathway is the conscious insight into the untruth of the phenomenal knowledge, for which that is the most real which is after all only the unrealized notion. On that account, too, this thoroughgoing scepticism is not what doubtless earnest zeal for truth and science fancies it has equipped itself with in order to be ready to deal with them — viz. the resolve, in science, not to deliver itself over to the thoughts of others on their mere authority, but to examine everything for itself, and only follow its own conviction, or, still better, to produce everything itself and hold only its own act for true."

This a critical historical reason that develops through our history.

July 14, 2005

understanding empire

There are lots of individual sovereign states in the world of nations. Only one, the United States of America, has both the will and the capacity to back international armed intervention and help deliver it, and talks about its international mission. After 9/11 the US neocons (ie., a Max Boot or a Robert Kagan) consistently said it was a choice between imperialism and barbarism.

What they did not say was that for an empire to be born, a republic has to die and that imperialism can become a barbarism.

How then, do we understand empire in the new world order of the post-cold war world? Consider this claim about empire made by Stan Goff:

"...the war in Iraq is symptomatic of a much deeper global crisis, and that it foreshadows a period in which that crisis, a crisis of global capitalism, will manifest itself not only in war but in rapidly widening social destabilization, the further militarization of the world system, and simultaneous economic and environmental collapse."

Okay. We can and should talk in terms of capitalism as a triumphant world system and a crisis of global capitalism, due to the failure to achieve self-regulating equilibrium and stability. The latter is what the G8 was meant to be talking about and addressing. But the global economic system we are a part of is not an empire, as that can be seen as self-regulating system with minimal governance, whilst empire would involve the military in some sense.

The global power for the US requires the US Department of Defense to currently maintain 725 official US military bases outside the country; to spend more on "defense" than all the rest of the world put together; and to do so even though the US has no present or likely enemies of the kind who could be intimidated or defeated by "star wars" missile defense or bunker-busting "nukes." It is a country obsessed with war: rumors of war, images of war, "preemptive" war, "preventive" war, "surgical" war, "prophylactic" war, "permanent" war. The US is a global power that is on the offensive and it stays on the offensive. As Thomas Friedman put it:

"For globalization to work, America can't be afraid to act like the almighty superpower that it is. The hidden hand of the market will never work without a hidden fist. McDonald's cannot flourish without McDonnell-Douglas. The hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley's technology is called the United States Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps." (T. Friedman, NY Times Magazine, 3/28, 1999).

Goff continues:

"Present-day imperialism is a real system, and itis currently directed by the American state. The war in Iraq was probably the inevitable action of this state in response to an impending and inexorable erosion of the very basis of American global power. The war in Iraq, while deeply morally repugnant, is not a failure of morality, but the action of a system that can't help it, because like the scorpion, it is that system's nature."

If system means empire, then the US is involved in a contest for supremacy in strategic, energy-rich regions like the Middle East and Central Asia.

But the US is not in Iraq just to get its hands on the oil so as to control the fuel supply to run its industrial machinery. Empire also involves the reshaping of the US. The signs are the corruption and abuses of power, unchecked executive power, the veneration of the presidential leader, Guantanamo, a domestic media that has become supine and subservient,and a Democrat opposition that is frightened of transgressing the consensus on "order" and "security".

Something has shifted. Are we seeing the transformation of the American democratic republic to something else? Is not empire in the process of being constructed before our very eyes by the Bush Republicans? A shift from republic to a militarized imperial power, to a self-tranforming empire?

If so, then the US as empire is not simply an expansion of late 19th century imperialism. This imperial machine is something quite different. It speaks in terms of order and peace as the old international order dies away and confronts its enemies--currently Islamic neofascism. Empire presents force as being in the service of freedom and democracy that gives order and peace.

Nor is scorpion the right metaphor for empire. Could not empire be better than what went before, in similar sense to capitalism being better than feudalism? Should we not try to see in negative and positive terms.

Goff continues:

"What is being sought is a new foundation, a military one, upon which to base US global supremacy as the current one is beginning to crumble. And reliance on direct military violence to achieve one's national aims is not a sign of strength, but a sign of weakness, a sign that there is a fundamental failure of hegemony. Hegemony is not direct control, but internalization of control by those who are dominated."

Does that mean that the economic foundation of empire is being undermined by the Chinese economic power? Is that the way to understand how US global supremacy is beginning to crumble? Goff says yes.

"The neoliberalism that underwrote the bacchanalia of the 90's is reaching its endgame and...we are witnessing right now is the particular neocon version of how that global architecture will be rebuilt---by dint of arms."

Yes, we are. But is the current rebuilding and use of U.S. power designed to advance a specifically U.S. national capitalism? Or,as Don Hammerquist, argues it is about using that military power to defend empire in the sense of the system of world capitalism as a global economy, political system and as a "civilization"?

I swing between the two. But I'm inclined to follow Hammerquist's argument that the neocon's understanding is that U.S. power should serve global capitalism, not the reverse.I stand with Hammerquist but then I look back to Goff and say yes. As I say I swing between the two.

July 12, 2005

Digital Democracy

John Quiggin's presentation to the Adelaide Festival of Ideas was about the significance of blogs and Wiki, given that they restore, and actualize, the early innovation and creativity promise of the internet. Does that mean that the free spirits of creativity are resisting the threat by the bulldozers carving out property rights? John's talk did not go on to link this decentered, networked media, and co-operative Wiki way of constructing knowledge, to citizenship in a liberal democracy.

In various comments to the media the Festival organizers had linked Festival's informed discussion of public ideas to influencing government decisions so as to improve them. Though improve, or making better, was left undefined (I presume they meant something along the lines of a better life and/or a more equitable society), the organizers identified themselves as working within "the project of Enlightenment".

Mark Cully says that he is an:

"...unreconstructed beliver in the enlightenment who's very much against postmodernism. I think that there are truths which can be established. Science progresses and we get closer to the final truth on things all the time. Through science I believe in truth, I believe that informed debate gets us closer to the truth and I think if we have informed debate then there's a better chance that government's might make sensible decisions rather than if there isn't an informed debate. You can't force governments to make sensible decisions, but if you have informed debate there's a better chance of that happening."

The Habermasian understanding of the Enlightenment project argues that the public sphere is a space in which reason might prevail. This is a critical reason that is a part of the democratic tradition, not the instrumental reason of much modern economic practice that is primarily concerned with growth, wealth and prosperity.

Whether this is Quiggin's position is not clear. I am going to attribute to the Festival of Ideas, in the sense that it underpins and makes sense of their practices.

We can take Quiggin's insights a step further by asking: 'Does the internet world of blogging and Wiki change the way we understand democratic politics?' 'Do we need to rethink the modern democratic tradition to understand citizenship in a digital world?'

I suggest that we rethink the liberal political tradition. One presupposition of the Habermasian public sphere, for instance,is that private citizens will enter into the public body by leaving behind their private concerns and focusing rationally on matters of the common good. The very architecture of the Internet pushes us to think beyond the modern antinomies of public and private, rather than simply utilize the old antinomies of classical liberalism under the conditions of digital capitalism. One kind of blogging means thinking critically about public issues from within the privacy of one's home.

An implication of Quiggin's talk is that new technologies should not be treat as purely instrumental means by for pre-existing goals. Such approaches, due to the deeper cultural reconfigurations that are at stake when the material basis of communication changes. I'm interpreting Quiggin strongly, to say that we should view media technologies such as blogging as having transformative powers.

We can develop this perspective through this 1995 text by Mark Poster. He says that:

"The question that needs to be asked about the relation of the Internet to democracy is this: are there new kinds of relations occuring within it which suggest new forms of power configurations between communicating individuals? In other words, is there a new politics on the Internet?"

He says that one way to approach this question is to make a detour from the issue of technology and raise again the question of a public sphere. The question then involves gauging the extent to which Internet democracy becomes intelligible in relation to the public sphere.

Poster says that to frame the issue of the political nature of the Internet in relation to the concept of the public sphere is appropriate because of the spatial metaphor associated with the term. He adds:

"Instead of an immediate reference to the structure of an institution, which is often a formalist argument over procedures, or to the claims of a given social group, which assumes a certain figure of agency that I would like to keep in suspense, the notion of a public sphere suggests an arena of exchange, like the ancient Greek agora or the colonial New England town hall."

It is an exchange understood in terms of an ongoing public conversation, or informed debate by citizens we can add. Or as Poster puts it, the public sphere is the place citizens interact to form opinions in relation to which public policy must be attuned. In the language of the republican tradition it is a space in which citizens deliberate about their common affairs.

The electronically mediated communications associated with the Internet mean that the face-to-face talk gives way to new forms of electronically mediated discourse. Poster points out that there is a history of electronic forms of interaction--he mentions the centralized top-down, information machines (radio and television) and their role in mediating politics. He says that the difference that is introduced by the networked media of the Internet is that:

"...it is a technology that puts cultural acts, symbolizations in all forms, in the hands of all participants; it radically decentralizes the positions of speech, publishing, filmmaking, radio and television broadcasting, in short the apparatuses of cultural production."

And it also allows for, and institutes, a communicative practice of self-constitution. This change in the way identities are structured discloses a space of a postmodern culture.

So what of the question posed earlier: is there a new politics on the Internet? Poster suggests that there is, and that it arises from the way that:

"The Internet seems to discourage the endowment of individuals with inflated status. ...If scholarly authority is challenged and reformed by the location and dissemination of texts on the Internet, it is possible that political authorities will be subject to a similar fate."

If this is so, then it represents a rupture with the old politics of the active expert addressing a passive audience and which only grants the space for the audience to ask a few questions at the end of the speech.

July 11, 2005

the banality of evil

The news reports are saying that, Bill Farmer, the CEO of the Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs Department (DIMA), has just resigned and been appointed as Ambassador to Indonesia, just prior to the tabling of the full report of the closed Palmer Inquiry.

This is John Howard's way of handling his damaged bureaucratic and political goods: decorate and promote them. He did the same over the Tampa incident with Jane Halton, who was rewarded for her blocking work by being made CEO of Department of Health and Ageing. What counts is delivering the political imperatives demanded by the government.

What can we say of Bill Farmer and his routinized mandatory detention work that imprisoned a mentally ill Australian citizen, failed to exercise duty of care, and resists all the way to the Federal Court attempts to have mentally ill detainees referred from the Baxter Detention Centre to Glenside Hospital for treatment?

Hannah Arendt's book, Eichmann in Jerusalem, comes to mind. Farmer was a little man who just "followed orders". He is an average man, a petty bureaucrat interested in furthering his career, who has little sense of responsibility for the damage he has caused, and diligently works to ensure that the department often evades or ignores its duty of care responsibilities.

What Arendt's book does is highlight the banality of the perpetrators of evil rather than talk about the banality of the evil deeds. This would interpret Farmer as terribly normal, rather than being a cruel, savage, sadistic person.

By normality is meant that he goes home at night to tend his garden and water his flowers many miles away from the barbed wire of the detention camps. He goes on vacation, is enthralled by the beauty of an Australian landscape, makes children laugh. Yet he can still fulfil regularly, day in and day out, the duties of administering the public laws and regulations that mentally scar and torment the imprisoned aslyum seekers.

That normality does not mean that Farmer is not responsible for his actions. He is. The trouble is that he is not being made accountable for his actions.

The banality of evil can also refer to the routinisation of work undertaken by Global Solutions Limited in running the Baxter Detention Centre, and to the legal details of the juridico-legal basis of the regime.

Taking responsibility is the first step toward combatting the evil that is mandatory detention. Many in DIMA refuse to take responsibility.

Update: 18th July

David Marr's clear account of the banality of evil in the day-to-day administration of DIMA.

Marr also indicates that the department has been at loggerheads with the courts for years over a fundamental question:

"what tests officers must apply when holding people in detention for any length of time---for anything more than, say, a few hours or days. Is it enough to "reasonably suspect" the person is unlawfully in Australia, or must officers be much, much more certain?"

Immigration believes reasonable suspicion is enough. But that is not what the courts say.

Marr says:

"Every time Solicitor-General David Bennett, SC, has bowled the reasonable suspicion argument up to the courts in the past few years, they have declared it a no-ball. Most recently, in 2003, a full Federal Court of three judges headed by the Chief Justice, Michael Black, unanimously declared that suspicion is not enough. To hold anyone in immigration detention for any length of time, the department must know they are unlawfully in Australia."

The Immigration Department operated in defiance of that ruling of the Federal Court. In Corneila Rau's case DIMA officers never established she was unlawfully in this country.

July 10, 2005

towards digital democracy

This post over at public opinion raises the issues of digital democracy. It argues for the need to revive and foster the political conversation in this country. A good way to do this is with a festival of ideas, as this provides a platform for people to express interesting, thoughtful ideas on topical issues. But we need to think through the relationship between a festival of ideas and democracy.

The public opinion post contextualized the Adelaide festival in the way that newspapers, radio, television and government spin constitute the informational framework of our lives, and still determine our reception of our ideas on topical issues and the way we put forward competing solutions. Public opinion suggested that the new media of the internet can, and should, provide a pathway out of the historical failure of the mass media to provide a forum for informed public debate by citizens concerned about their country.

Public opinion then criticised festival for failing to make this move to become a part of a digital world. I'm going to give some reasons here for why we need to make the move. It builds on earlier posts here and here

The Internet is new media, not just because of the technology. Though many see the Internet as a place to use words and text, others, informed by television, see it as a world of images and pictures. Public opinion assumed that the new technologies could be deployed to improve democracy, enhance civic discourse, and help the spread of a democratic political culture in oppposition to the commercial use of the internet.

In Australia democracy is representative democracy, what can be called 'weak democracy', as citizenship is limited to voting. Thsi has the following consequences: ordinary citizens can feel privatized and marginalized; the voter votes once every three years and then goes home and watches political events on the news, waits till the next election. Inbetween elections he or she lives privately as a consumer or a client letting her elected representatives do the governing. Often we have party elites and powerful leaders manipulating issues to win over impassioned, but disengaged, subjects, and gain populist approval for their hegemony.

The Adelaide Festival of Ideas introduces the active citizen who are engaged in the discussion of ideas, thereby adding to the idea of active citizens in their neighborhoods, towns, schools and churches. This presupposes social capital and trust in civil society, which is quite different from the social cohesion desired by representative-style liberal governments. The ethos of the festival--informed debate, challenging ideas, trying to shape government decisions--points to participatory democracy. But that is what we don't have in Australia.

One advantage of a Festival of Ideas embracing a digital world is its speed. Computer communication permits instant communication. This does not mean instant thinking; it does mean using the speed to post the festival speeches on a website to enable democratic deliberation. We e-citizens can read then the material at our lesiure, treat the ideas with patience and consideration. We can download them, mull over them, sift them, reconsider them, use them to question our own thinking.

That kind of critical filtering enables us to avoid the instant thinking and chatter in the form of the venting of our unfiltered prejudice and unthought opinions; and so it allow us to develop our civic and political judgement. This provides a space to avoid the mass media's relationship to democracy caused by the media's inclination to reductive simplicity, binary dualisms of left and right. It also allows us the space to explore the complexities and possibilities of the common ground between two polar alternatives.

It is often argued that a digital world has a tendency to divide,isolate and atomize people because of the necessary solitude of the computer terminal. We sit alone in front of keyboards and screens and relate to the world only virtually, our bodies in suspension, whilst we surf the net. Surfing alone leads to the privatization of politics.

This argument fails to take into account the blogging publishing platform with its public posts, comments, linkages, discussion and common deliberation. This provides a forum where those with something to say are obliged to face public scrutiny of their prejudices and publicly defend their views. So we don't just have the solitude or hyper-individualism of the virtual interface.

Benjamin Barber acknowledges the existence of the virtual communities that have been created on the Internet, but argues that they:

"...are narrow communities of interest,in effect, special interest groups comprised by people who share commonhobbies or similar identities or identical political views. Or they are a continuation of communities forged in real time and space. It's one thing to use the net to reinforce an extant community, quite another to create acommunity from pixels alone. And often, communities that use the web to spread their nets do so in the name of resistance and terror-- radical fundamentalist Christians and Islamic Jihad (not to speak of the Neo-Nazi movement)---have all used the internet to forge something like a trans-national political community. Ironically, almost all conference addressing the potential of the newcyber-technology meet in real time and space--their modus operandi standing as a living reproof to the cyber-communitarian theories they celebrate."

But bloggers do create a virtual community from their posts in spite of the partisan nature of political discourse. Barber has another objection:

"It is hard enough to determine whether cyber-community is feasible; even if we assume it is, this leaves open the question of whether democracy is likely to benefit. Representative democracy, founded on the pluralism of interests and groups and rooted in individualism and rights theory, puts little stock in communities to begin with, and its advocates are unlikely to feel benefited by whatever good deeds the new technology can perform on behalf of community. Strong democrats, on the other hand, may feel that the technology’s ultimate benefit to participation will rest entirely on its capacity to contribute to the building of the kinds of community on which spirited participation and social capital depend."

This ignores the value of the online public discussion of ideas, the debate that takes place and the deepening understanding that comes from this conversation. The publishing technology provides micro but interlinked forums for citizens to participate in a conversation that takes us beyond asking a few questions at the end of a well presented talk by an expert in a festival of ideas.

July 9, 2005

the state of exception is the norm

The situation of the state of emergency or exception becoming the normal since 9/11 is now acknowledged in the Australian media. It is no longer the odd idea of fascists like Carl Schmitt undermining the liberal democratic Weimer Republic or odd Italian philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben.

Andrew Lynch, the director of the terrorism and law project, Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, at the University of New South Wales, writing in The Age makes the point that after 9/11 the state of emergency is becoming the normal.

He says that:

"The shocking terrorist attacks in London are a powerful confirmation of our times. While we can say that "the world changed on 9/11", the London strikes force us to realise that we are now living in that altered world - one that exists in a state of anticipated emergency."

Lynch goes onto say that as we slide into a state where what was exceptional is now the new norm, since 9/11, most Western democracies have sought to increase security through legislative measures that increase the powers of executive bodies such as ASIO.

"In doing so, many of the human rights we took for granted - no detention without charge, freedom of the press - have been diminished.There has been opposition to these sacrifices, but on the whole, the public seems to have thought the price worth paying. This is presumably because exceptional times call for exceptional laws."

Lynch gives us a genealogy of the state of exception:

"There is a long history of such pragmatic responses to threats to the wellbeing of the state. The Roman republic was prepared to cast aside its normal form of governance in favour of a temporary dictatorship to meet these challenges effectively. The Churchill government in World War II was similarly a "crisis government" imbued with extraordinary powers felt necessary to achieve victory.But those examples were "exceptional" in the true sense. Once the danger passed, the executive government's power returned to its normal state limited by constitutional and political checks. Citizens once more enjoyed the rights they had earlier taken for granted."

Not so today. Our present state of emergency is the new norm.

What does that mean?

Lynch says that it will mean that:

"...the quite extreme way in which national security has been prioritised over human rights in the past few years will solidify. The hallmark of the new norm will be increased deference to the opinion of the executive arm of government....Any signs from that case that governments were going to be held to account for the way in which they have eroded rights in the name of security have been superseded by far more disturbing images."

The state of emergency as our new norm is what we are living. That is as far as Lynch takes it.

We could write state of emergency as the new norm as the state of exception as the new paradigm of government. We could then ask what is the state of exception we are living?

July 8, 2005

a situation of emergency requires that ...

I've been listening to the G8 leaders and the conservative commentary on the London bombings. What I'm hearing is a particular kind of discourse that is buried within the chatter about terrorism and the rally around the flag patriotism.

The discourse says that the Islamic terrorists threaten the destruction of democracy itself, with all the values that democracy embodies and protects. In order to combat this threat effectively, democracies need to do acts that are evil in themselves but constitute a lesser evil than that posed by terrorism.

Another strand of the discourse is that we are caught up in a war on terror. The actions of Al-Qaeda are those of terrorism; terrorism cannot be countered by political means; it can only be met by war. And war entails the use of coercion, force, and violence.

Another strand is that we have to do all that is necessary to ensure the security of the (American, or Austrlaian, or British etc) people. So it is necessary that democracy, with its rights and liberties, may require an abrogation of at least some of its rights and liberties, at least for some persons and for a limited time.

It's a situation of emergency that makes it right to do this in the service of good of the civilised freedom loving peoples.

That is the conservative discourse I've been hearing in the wall to wall media commentary around the London Bombings. It makes me uneasy. But I'm not sure how to tackle it.

What is easy to say is that the state of emergency (or exception) has become the normal:--that is the insight of some of the work of Giorgio Agamben.

But I'm not sure how to deal with the ethics of this. On the one hand we have those saying that it is necessary constraining liberty in democracies to deal with threat of evil. On the other hand, we have libertarians talking in terms of the erosion of basic human rights by the national security state.

July 7, 2005

finding my way to Arendt

My thinking is rather crude.

I juxtapose instrumental reason (utilitarianism) with practical reason (dialogic reason concerned with the good life.) I do so in an attempt to disclose a dimension of action and freedom that transcends the Weberian problematic of rationalization and its discontents.

That problematic takes the form of instrumentalizing the world; is motivated by a will to manipulate or control nature and society; operates in terms of a means/end rationality in which things only make sense as means to a pre-given end; makes usefulness and utility the standards of life in modernity; utility leads to meaninglessness or nihlism.

What is juxtaposed to this is a conception of the political life of citizen and citizenship which presupposes that not all politics is domination. The stuff of everyday contemporary politics is about administration and management instrumentalizes the political, and is concerned with, and presupposes, domination.

It seems that I'm inching my way to Arendt.

July 4, 2005

rhetoric and conversation

Martin Krygier has an article on the rhetoric of reaction in the Review section of the Australian Financial Review. It really ought to be online. But see here.

Krygier works with the modern, negative conception of rhetoric to explore the way the rhetoric of reaction has function in terms of the history debates about the violent Aboriginal/settler relations in Colonial Australia through the use of the tropes of Holocaust and genocide. He says:

"The rhetoric of reaction is a device intended not to further the flow of conversations among citizens, but to dam it up or redirect it into unthreatening channels. Where it is the characteristic mode of intervention, it should, I believe, be exposed and criticised."

This 'rhetoric of reaction, is born out of a desire to deny, divide and abuse, does considerable damage. This is all very familiar and it expresses the partisan nature of this kind of polemics (not debate) in Australia. The effect it has had is I do not even bother reading the books I see on the shelves of bookshops on the history war of words.

Krygier defends the regulative ideal of conversation as distinct from a war of words, and asks:

"What is needed, then, for real engagement in conversation? One answer can be stated in simple, even, banal terms: a conversation necessarily has more than one party, and it is a pecularity of the particpants' engagement, as distinct from a monologue, a harangue, a tirade, a shouting match, that they treat each other with respect."

He then asks:

"What might that [conversation] involve, particulary when passions are high and moral energies charged?"

Krygier says that he does not have clear answers to this. He does insist that a rhetoric of critique can be similar to a rhetoric of reaction as a mirror does a reflection:

"It relentlessly moralizes about what other with equal determination seeks to sanitize, exaggerates what the other is determined to minimize, demonises what the other sanctifies, closes off exactly the complexities that the other also denies, but for opposite ends."

That describes a lot of left-liberal critique in Australia.

Anyone concerned with the conversation of citizens has a responsibility to avoid both debased forms of rhetoric.

July 2, 2005

Manifest destiny: freedom & empire US style

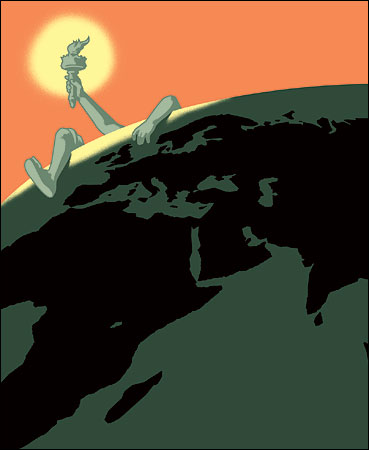

Christopher Niemann's image is about the American democratic light lightening up a non democratic world:

According to Thomas Jefferson the American form of republican self-government would become every nation's birthright.

According to Thomas Jefferson the American form of republican self-government would become every nation's birthright.

That is the core of Americans mean when they talk about the manifest destiny of the US.

Jefferson went on to say that democracy's worldwide triumph was assured because "the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion" would soon convince all men that they were born not to be ruled but to rule themselves in freedom.

It is US nationalism universalized to the world spirit. President Bush expresses this in terms of freedom as God's plan for mankind.

So what happens when the world spirit of reason and democracy becomes connected to empire, hegemony, power politics and national interest in a world of nation-states?

It is addressed by Michael Ignatieff in the New York Times Magazine. You can find some comments over at Williams Burrough's Baboon by Glenn Condell here and wbb here. For more commentary see Technorati

Ignatieff says that:

'In the cold war, most presidents opted for stability at the price of liberty when they had to choose. This president, [ie. President Bush] as his second Inaugural Address made clear, has soldered stability and liberty together: "America's vital interests and our deepest beliefs are now one." As he has said, "Sixty years of Western nations excusing and accommodating the lack of freedom in the Middle East did nothing to make us safe---because in the long run stability cannot be purchased at the expense of liberty."'

Ignatieff says that it is terrorism that has joined together the freedom of strangers and the national interest of the United States. On this account democracy in the Middle East will actually make America safer.

To his credit Ignatieff defends this position by addressing the issue of empire. He says that the charge that promoting democracy is imperialism by another name is baffling to many Americans. How can it be imperialist to help people throw off the shackles of tyranny? The short and long answer is by overthrowing other peoples' governments and by invading and occupying other countries.

Ignatieff responds to this as follows:

'The problem here is that while no one wants imperialism to win, no one in his right mind can want liberty to fail either. If the American project of encouraging freedom fails, there may be no one else available with the resourcefulness and energy, even the self-deception, necessary for the task. Very few countries can achieve and maintain freedom without outside help. Big imperial allies are often necessary to the establishment of liberty. As the Harvard ethicist Arthur Applbaum likes to put it, "All foundings are forced." Just remember how much America itself needed the assistance of France to free itself of the British. Who else is available to sponsor liberty in the Middle East but America?'

He says that it is not imperialistic to believe believe that most human beings, if given the chance, would like to rule themselves.

No it is not. It is imperialistic to invade and occupy a foreign country that does not threaten your national interest and then to invent fictions about the threats posed.

Ignatieff acknowledges that many foreigners do not happen to buy into the American version of promoting democracy and that many American liberals don't share the vision either.

July 1, 2005

Hegel: on constitutions

Hegel holds that a constitution expresses the broader values, practices, and traditions of the culture of the nation-state. I'm working off this article by Andrew Buchwalter entitled 'Constitutional Paideia: Remarks on Hegel's Philosophy of Law'

This expression is not just in the Burkean sense that a constitution is inextirpably shaped by a culture's received traditions and practices, but also in Montesquieu's sense that a constitution has force only inasmuch as it articulates the values and assumptions that account for social cohesion. A constitution can have binding value for a people only to the extent that it expresses "the customs and consciousness of the individuals who belong to it."

We rarely hear this view expressed in Australia, where the constitution is seen as a stand alone legal document.

Hegel's thesis is that what he calls the "political constitution" cannot be identified with the legal constitution as such (Verfassung). The former denotes that broader assemblage of norms, institutions, and customs that defines a nation and gives meaning and validity to particular institutions, formal agreements and procedures included.

However, Hegel does more than embed a legal constitution within the culture and ethical life of a people living within a nation-state. For a constitution to express the culture of a people, it must also accommodate processes through which a culture routinely refashions inherited traditions so as to ensure their applicability to changing social circumstances. So a constitution can be understood as a transmitted legacy whose vitality requires renewal through a community of interpreters who reappropriate and clarify legal-political traditions, principles, institutions in light of present realities.

Thus in paragraph 344 of the Philosophy of Right he says:

In the course of this work of the world spirit, states, nations, and individuals arise animated by their particular determinate principle which has its interpretation and actuality in their constitutions and in the whole range of their life and condition. While their consciousness is limited to these and they are absorbed in their mundane interests, they are all the time the unconscious tools and organs of the world spirit at work within them. The shapes which they take pass away, while the absolute spirit prepares and works out its transition to its next higher stage."

Hegel recognizes the political reality that a people is already constituted. As they were in Australia before the constituional referendums in the 1890s.