March 31, 2006

a question

A good question. How should one read Carl Schmitt's Der Nomos der Erde ---The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europeaum--- in view of the present European-American controversy about the unilateral assertions of power by the US?

On this Martti Koskenniemi says:

One alternative is to suggest that its critical analysis is largely correct.The United States is embarked on a morally-inspired crusade opposed by a Europe that invokes the formal law of sovereign equality under the United Nations Charter. There is undoubtedly something right in such an analysis. It is especially hard to avoid thinking about the American rhetoric of freedom as anempty form through which the United States asserts its unconditional sovereigntyover the world. This would be empire, and the only remaining question would be whether it is a "rational empire," inspired by genuine confidence in the universalityof the moral truth for which Washington decision-makers see themselves ascarriers (in Schmittian terms, the United States as a kind of "commissarial dictatorship" upholding the substantive constitution of the world by a suspension of its formal provisions); or whether the right characterization would be of a "cynical empire," lacking such faith though still using its language. Both alternatives would be compatible with understanding American acts in terms of a political theology (of freedom) in the strict Vitorian sense: one's unconditional deference to right authority as the sole standard of evaluation, whereby one's acts would be automatically virtuous whether their consequences were good or evil... This is the logic of (American) nationalism: the unquestioned authority of my (liberal democratic) country as the sole normative standard..

Well that is how I read the US assertion of unilateralism and hegemony--a cynical empire-- even though I do have doubts about the European conception of international law as a system of rules based on universal values expressed as human rights.

March 30, 2006

Tronti's 'Strategy of Refusal' #2

Back to reading Mario Tronti's Strategy of Refusal, which I'm reading in the context of a political campaign in Australia against the deregulation of they need to sack their workforce, and street marches in Paris as part of a continuing protest over a new jobs law. Tronti say:

This is the historical paradox which marks the birth of capitalist Society, and the abiding condition which will always be attendant upon the "eternal rebirth" of capitalist development. The worker cannot be labour other than in relation to the capitalist. The capitalist cannot be capital other than in relation to the worker. The question is often asked: "What is a social class?" The answer is: "There are these two classes". The fact that one is dominant does not imply that the other should be subordinate. Rather, it implies struggle, conducted on equal terms, to smash that domination, and to take that domination and turn it, in new forms, against the one that has dominated up till now. As a matter of urgency we must get hold of, and start circulating, a photograph of the worker-proletariat that shows him as he really is - "proud and menacing". It1s tine to set in motion the contestation - the battle, to be fought out in a new period of history -directly between the working class and capital, the confrontation between what Marx referred to in an analogy as "the huge children's shoes of the proletariat and the dwarfish size of the worn-out political shoes of the bourgeoisie".

Well, we are currently living in a moment of contestation and battle around the hegemony or domination of capital in Australia.

Tronti adds that:

It is the directly political thrust of the working class that necessitates economic development on the part of capital which, starting from the point of production, reaches out to the whole of social relations. But this political vitality on the part of its adversary which is, on the one hand, indispensable to capital, is, at the same time, the most fearful threat to capital's power. We have already seen the political history of capital as a sequence of attempts by capital to withdraw from the class relationship; at a higher level we can now see it as the history of the successive attempts of the capitalist class to emancipate itself from the working class, through the medium of the various forms of capital's political domination over the working class.

That is what we are seeing being played out in Parliament---the political domination of capital--what Tronti calls the political dictatorship within democracy as the modern political form of class dictatorship. The working class is certainly on the defensive, as the labour conditions it has struggled for over the last 50 years are being rolled back. We have 'the State of capitalist society.'

So what are the differences between the two forms of political power?

The difference between the two classes at the level of political power is precisely this. The capitalist class does not exist independently of the formal political institutions, through which, at different times but in permanent ways, they exercise their political domination: for this very reason, smashing the bourgeois State does mean destroying the power of the capitalists, and by the same token, one could only hope to destroy that power by smashing the State machine. On the other hand, quite the opposite is true of the working class: it exists independently of the institutionalised levels of its organisation This is why destroying the workers: political party does not mean - and has not meant - dissolving, dismembering, or destroying the class organism of the workers.I'm not convinced that the working class exists independently of the institutionalised levels of its organisation.

The working class's organizations in the form of the peak union body --the ACTU-- was a part of the bourgeois state under the Hawke/Keating Labor government during the 1980s and 1990s, and it helped to shape economic policy under the Accord as the Australian economy was opened up to the international one. In the old Marxist language it had been incorporated and it delivered lower wages for an increased social wage --that was the tradeoff.

What is the working class outside the union and the ALP? Non unionised labour? Casual workers? Part-time workers?

March 29, 2006

enemies and friends in politics

Schmitt's The Concept of the Political provides a positive definition of the political, as against both the contrasting definitions of social scientists and philosophers by playing off the political against the economic, the moral, etc. This 'definition of the political,' Schmitt tells us, 'can only be obtained by discovering and defining the specifically political categories' (p. 25). Politics allows for the existential affirmation of who and what we are, both as individuals and as a potential 'fighting collectivity'.

Schmitt provides his readers with the following definition. Politics is about friend/enemy groupings and the antagonism between friend and enemy is connected to protecting the way of life of a particular people. The us/them grouping becomes the friend/enemy grouping precisely at the point where the way of life of a collectivity becomes threatened. The enemy 'is one who threatens one's own existence and way of life.'

The individual citizens of a particular state see their enemies and friends not as 'my enemy' and 'my friend', but rather as 'our enemies' and 'our friends'. In The Concept of the Political Schmitt says:

The enemy is not merely any competitor or just any partner of a conflict in general. He is also not the private adversary whom one hates. An enemy exists only when, at least potentially, one fighting collectivity of people confronts a similar collectivity. The enemy is solely the public enemy...(p. 28).

The friend is to be understood only in relation to the enemy, and no positive theory of friendship per se is developed in Schmitt's account.

March 28, 2006

federalism's blind spots

In advanced democracies citizens, public interest groups, and even political elites show decreasing confidence in the institutions and processes of representative government that is coupled with an erosion of support for core representative institutions.My argument is that the federal system is not working as designed.

This sums up a problem confronting liberal democracries:

Democracy is rule by the people. That's what democrats celebrate and what democracy's critics condemn. The critics, around since Plato, have an important argument. The people, they say, are neither sufficiently informed nor sufficiently reflective to rule. And because the people are not fit to rule, they need to be governed by an elite whose members---like Plato's philosopher-kings---think harder and know better.The American founders were troubled by this problem and proposed an answer to it. Their solution---defined by James Madison---was to make deliberation a key part of the design of the American democratic republic. The idea was "to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens"--to filter public opinion through representatives who would deliberate about public issues....The rise of political parties---more interested in competing for office than deliberating about policy---interfered with this vision.

They sure have, even though they are one form of representative democracy.

Madison had argued in The Federalist No.10, that the republican or federal remedy embodied in the Constitution allowed the various factions of public opinion sufficient room to express their views and to attempt to influence the government. Instead of the majority putting down minorities, the different interests would negotiate their differences, thus arriving at a solution in which the majority would rule but with due care and regard given to minorities. The very number of factions would preclude any one from exercising tyrannical control over the rest. And the medium in which this give and take would occur would be politics, the art of governing.

One way to achieve this is to divides national powers into three branches, and then allows each branch to check the others while preserving their independence. The purpose is to diffuse power and allow ambition to counter ambition. The assumption is that the different branches will have different interests premised on their institutional loyalties. The Prime Minister/Cabinet will seek to protect and extend executive power, the Congress (Parliament) legislative prerogatives, and the courts judicial authority.

There is no mention of legislature political parties in this. Yet the mediation of factions and public opinion takes place through the political parties. These allowed groups with very different interests to pool resources, make compromises, and push for common agendas; Alas parties now control the way parliament is run. The party system has managed to a consolidate power in the national government through the executive, and threatens the system of checks and balances. Worse one party can controlled all the branches of government.

The party system overwhelm Madison's carefully designed federal system of checks and balances. The executive then forms alliances with big industry and finance and this controls public policy. What we have is what Madison most feared: the concentration of power in the most dangerous branch---the executive branch, which Madison viewed as dangerously prone to war. Do we not have breaches of public trust here through an abuse of power?

The argument is this.

Parliamentary elections generally place a single party decisively in power, sometimes on a minority of the popular vote. The majority government and the permanent bureaucracy fuse into a dominant executive, protected from proper scrutiny by secrecy and operating in a context of informal guidelines and discretionary power. The executive dominates Parliament and through Parliament is superior to the judiciary, and neither they nor any other bodies provide effective checks and balances on its conduct of public affairs.

Madison' s solution is for the press to be free to censure the Government. The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. The press publicizes misconduct and overreaching so that other government officials and politicians can take action.

So what happens when the press becomes an advocate of the policies of the dominant executive? That means less check on executive power. That means the check's and balances on the government's ambition, hubris and bad judgment, which ensures the government to behave more responsibly, are not working as designed.

March 27, 2006

liberal interventionism & Carl Schmitt

I see that Carl Schmitt's seminal work with an international focus, Der Nomos der Erde has recently been made available in English--it has been translated by G.L. Ulmen as The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europeaum. (Telos Press, 2003). One strand of argument is that the French Revolution on, wars were being increasingly fought over moral doctrines ----most recently over claims to be representing "human rights." Such a tendency has replicated the mistakes of the Age of Religious Wars in that it has turned armed force from a means to achieve limited territorial goals, when diplomatic resources fail, to a crusade for universal goodness against a demonized enemy.

Is this not what has happened with Tony Blair's use of liberal universalism and liberal interventionism against international terrorism? He sees it a struggle about values and about modernity--about goodness versus badness. Blair comes across as if he were on a crusade against the people who hate us. His war is a struggle about justice and tolerance as well as security and prosperity and it is a reworking of Republican Washington's view of the world as sharply divided between "us" and the "enemies of freedom" .

One can read their conception of the war on terrorism through the lens of Schmitt's The Nomos of the Earth. Theirs is is a morally-inspired and unlimited "total war," in which the adversary is not treated as a "just enemy"; their war highlights the obsoleteness of traditional rules of warfare and recourse to novel technologies--especially air powe ---so as to conduct discriminatory wars against adversaries viewed as outlaws and enemies of humanity; Camp Delta in the Guantanamo naval base with its still over 500 prisoners from the Afghanistan war is a normless exception that reveals the nature of the new international political order of which the United States is the guardian --- the source of the normative order, itself unbound by it.

This quote sums up the ethos of liberal interventionism with military force in international affairs:

"The day will come, we are convinced of it, when we are going to be able to say to a dictator: 'Mr. Dictator we are going to stop you preventively from oppressing, torturing and exterminating your ethnic minorities.'"

Australia and the UN in East Timor is a classic example. Clinton and NATO intervening in the Balkans to protect Kosovo is another. Liberal democracies should intervene to stop atrocities, or help people to establish liberal democracies; and no absolute principle of national sovereignty, or fear of US imperialism, should stand in their way.

The harder more militant edge of liberal interventionism is the conception of liberalism as the battle for universal freedom, and as a revolutionary project for universal liberation by bringing about political revolutions in remote corners of the world. This provides the justification for the liberal hawks intervention in Iraq by the UK, US and Australian governments---they did so in order to liberate the Iraqi people from tyranny and bring them freedom and democracy. This example of a Liberal Interventionist rationale for intervention is what is advocated by Tony Blair, the British Prime MInister. As a liberal hawk he sees himself as a defender of the legitimacy of humanitarian intervention and he is an advocate for the role of idealism and values in foreign policy.

Liberal interventionism is different from Conservative interventionism, as the latter is essentially dressed up imperialism---actions are done in order to serve the empire's self-interest. Foreign policy should concern itself exclusively with the national [imperial] interest and exclude consideration of human rights and liberal values.

Schmitt also argued in The Nomos of the Earth that there is tendency toward a universal state that seemed closely linked to Anglo-American hegemony (a "New World Order"?). Americans, Schmitt argued, aspire to a world state because they make universal claims for their way of life. They view "liberal democracy" as something they are morally bound to export. They are pushed by ideology, as well as by the nature of their power, toward a universal friend/enemy distinction.

March 26, 2006

neo-con illusions

In this review by John Gray of Francis Fukuyama's After the Neo-Cons: America at the Crossroads, which was based on lectures given at Yale University last year, highlights that Fukuyama's thesis of the end of history does not mean that history had ended. It means that only one type of government would be legitimate. This is because American-style "democratic capitalism" embodies the only viable model of modern society, which the rest of the world must adopt.

Note the 'must. ' It's questionable in the Middle East or in China, even though one can accept "the use of American power to achieve moral purposes".

Gray points out that despite his criticism of the Bush Administration-- on the grounds that its foreign policy has retarded the process of Americanisation, as it has triggered a global blowback against US power-- Fukuyama remains:

...wedded to some of the most dubious features of neo-con ideology. He continues to hold to a view of history as leading to the universal triumph of an American model, and seems still to share the neo-conservative view that democracy is bound to promote peace.

So the Fukuyama's general triumphalism that followed the end of the cold war is stilll there in a more muted form---it is now shaped by the conservative values of scepticism, stewardship and prudence.

March 24, 2006

IR Reforms, Tronti, and the strategy of refusal

This text, The Strategy of Refusal' by Mario Tronto is courtesy of Long Sunday. They are having a symposium on the strategy of refusal--on concept of the working class refusal : the refusal of work, the refusal of capitalist development, the refusal to act as bargaining partner within the terms of the capital relation.

The 1960's text about class struggle interests me, given the Howard Government's recent industrial relations reforms--- Workchoices---and the subsequent resistance by the unions and the ACTU to a de-regulated labour market ; a resistance grounded in a refusal to accept the demolition of both the tradition and institutions of centralized bargaining and the shift to individual contracts between employer and employee.

This kind of refusal is a going back to basics of class struggle; one in which, on the classic Hegelian-Marxist account, a class can be said to exist in opposition, but only to constitute itself through political struggle. The working mass or mulitude becomes united, constitutes itself as a class for itself, and the interests it defends becomes class interests. On this classic account the struggle of class against class is a political struggle.

This struggle is currently mediated in federal Australia by the resistance of all the ALP state governments to the reforms of commonwealth Government; a challenge about the use of the corporations powers of the coomonwealth that will be resolved in the High Court. The resistance to the reforms is widespread in the national community with refusal actions of the ACTU being widely supported.

So what light can Mario Tronti throw on this kind of resistance as refusal?

He reverses this classic Marxist account:

So, can we say that we are still living through the long historical period in which Marx saw the workers as a "class against capital", but not yet as a "class for itself"? Or shouldn't we perhaps say the opposite, even if it means confounding a bit the terms of Hegel's dialectic? Namely, that the workers become, from the first, "a class for itself" - that is, - from the first moments of direct confrontation with the individual employer - and that they are recognised as such by the first capitalists. And only afterwards, after a long-terrible, historical travail which is, perhaps, not yet completed, do the workers arrive at the point of being actively, subjectively, "a class against capital".

I'm not that fussed by the reversa---see here for a theoretical discussion .The reversal kinda makes sense of our history in Australia. I guess the reversal grants the working class the offensive in the class warfare. Yet it would need to be an offensive within capitalist domination over society, that is based on the command over the forces and relations of production.

The working class in Australia---the shearers--were recognized as a class by the pastoralists who reckon the shearers had to be kept in their place, and their strikes for better working conditions had to be broken. The response by the shearers in the 1890s was political---to form their political party to improve their conditions. It is a strategy of refusal to accept the political realities of pastoral capitalism as well as a strategic way to struggle against the domination of pastoral and merchant capital. Politics is the key to the class struggle from Federation onwards.

Tronti address the party. He says:

A prerequisite of this process of transition is political organisation, the party, with its demand for total power. In the intervening period there is the refusal - collective, mass, expressed in passive forms - of the workers to expose themselves as "a class against capital" without that organisation of their own, without that total demand for power. The working class does what it is. But it is, at one and the same time, the articulation of capital, and its dissolution. Capitalist power seeks to use the workers' antagonistic will-to-struggle as a motor of its own development. The workerist party must take this same real mediation by the workers of capital's interests and organise it in an antagonistic form, as the tactical terrain of struggle and as a strategic potential for destruction.

Presumably by the workerist party Tronto means the Communist Party. Such a party no longer exists in Australia. All we have now is a social democrat party ---the ALP. This was explicitly formed as an organization to further the interests of the unionised working class. However, the ALP was never a party for the destruction of capital--it was a party primarily concerned to stabilise and modernize the development of the capitalist system. The ALP is not simply a workerist party.

Tronti says that:

The working class cannot constitute itself as a party within capitalist society without preventing capitalist society from functioning. As long as capitalist does continue to function the working class party cannot be said to exist.

Hmm. What we have in Australia is a working class organized in terms of the ACTU and the ALP, with all the strands of the movement seeking to further the interests of workers within the social relations of capital as they seek to accommodate themselves to the impacts of globalization on their working lives. This 'furthering' had involved reforms as tradeoffs----ie., the Accord-- during the 1980s-1990s when the ALP had formed government.

March 23, 2006

the power of lobbyists

We have explored the effect on Parliament and government of the power of the lobbyist before. And there is more on public opinion here and here

What comes through is the fear of the state premiers off upseatign the coal and eneergy intensive industries by adopting a strong Greenhouse policy.

In an entry on July 16 2004 in his Latham Dairies Mark Latham says:

I followed up in Melbourne yesterday with a cooparative agreement with the Premiers sans Beattie, about needs-based schools funding and health system reform eliminating waster and duplication. We wanted to include Kyoto in the agreement by setting up a national-carbon trading system, but Beattie refused to cooperate, so it had to be dropped. He's super-sensitive about the coal industry, but it's crazy in term sof Queensland's long term interests. Global warming is killing the Great Barrier Reef, the State's main economic and environmental resource, and Beattie won't support Kyototo do soemthing about it. ....he's rough-riding over the Reef, watching it die because of coal bleaching. (pp.317-18)

So there you have--a classic example of the power of lobbyists.

March 22, 2006

offshoring jobs: some questioning

We increasingly read in the media about about jobs ---manufacturing, call centres, services--- moving offshore becvause they can be done more cheaply. Conventional economists say that this "offshore outsourcing" -- ie., the migration of jobs, but not the people who perform them, from rich industrial countries to poorer industrial ones--- is "the latest manifestation of the gains from trade, which economists have talked about at least since Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Countries trade with one another for the same reasons that individuals, businesses, and regions do: to exploit their comparative advantages. Offshoring of jobs is simply international business as usual.

It is what the global market is all about, isn't it? Globalisation mean increased trade and investment across national borders. There are the potential benefits of services offshoring, such as lower consumer prices and increased living standards for Australians.

Surely globalisation has costs as well as benefits. For instance, what happens to those left without jobs? Surely pockets of workers will lose jobs due to offshoring? Well, it is expected that they move on to find new jobs in a prosperous and growing economy. No problems. That's how the new global order works: those that remain in the car or manufacturing industries, or in computing, will be in competition with those workers in India.

Still we are uneasy. Isn't that what Qantas is planning to do--offshshoring skilled maintenance jobs? Isn't there a disruptive effect on Australia? Will the loss of jobs abroad through offshoring be made up for by the creation of quality jobs at home? Does not offshoring pose a major industrial restructuring challenge? What would the potential impact be region by region? I remember the industrial restructuring of the 1980s and 1990s that inflicted so much economic and social damage because of the lack of an effective policy response through industrial, regional and labour market policy. Instead, blind faith was put in the market. Is this what is happening to day?

And what about this scenario?

The reality of globalization combined with the de-unionization of the workforce under the new industrial relations laws could well combine to make rising incomes for many Australian households a a thing of the past, in spite of increasing productivity.

The response is that education is the key in the global economy. We need to upskill so education is what is needed. You know 'knowledge' nation and the 'high tech' economy rather than the pathway of the low wage low skilled workers. However, isn't it the more highly skilled service-sector workers--rather than the dishwashers, plumbers and cleaners who are likely to have tradable jobs? So what happens to this professional middle class? Let them be?

Is that right? I'm not sure. I cannot put my finger on it what's missing. Isn't all the emphasis is on education as a particularized vocational ed in the context of improving Australian global competitiveness a response to this? Isn't all the talk about support to encourage training and upskilling to allow staff to redeploy to high value added jobs, including the extension of lifelong learning opportunities in IT a response to offshoring?

March 21, 2006

The ALP reflects on indigenous policy

The End of Ideology in Indigenous Affairs speech from Senator Chris Evans, the Shadow Minister for Indigenous Affairs is an interesting one. He rightly says that thirteen years of Labor government and ten years of the Coalition:

...have not delivered substantially improved outcomes for Indigenous people. On the key indicators in health, education, employment and housing success is minimal and in some cases the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous outcomes has widened. While both sides of politics have continued the ideological war, Indigenous people have continued to live in third world conditions, and the disillusionment of the wider community has grown.

Then some self-criticism of the traditional ALP approach to improving Aboriginal wellbeing:

Labor in government pursued an agenda that focussed on rights, reconciliation and self determination. Labor is proud that its agenda led to the establishment of ATSIC, the Mabo legislation, the Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Inquiry, the Indigenous Land Fund and the Reconciliation Council. Labor invested a great deal of energy and political capital into this agenda and we are despondent at the Howard Government's undermining of so many of these measures. Labor's ideological commitment to the rights agenda, self-determination and reconciliation was not matched by a successful attack on the fundamental causes of Indigenous disadvantage. We put too much faith in the capacity of the rights agenda to contribute to overcoming entrenched Indigenous disadvantage.

That self-reflection is refreshing to see. The rights agenda was narrow and limited, and the failure to deliver substantial improvements in Indigenous well-being provided conservatives with an opportunity to trash the real achievements of the Hawke / Keating period. It gave the Howard Government's the space to reject of self-determination and Aboriginal participation in decision making and service delivery; to encourage Indigenous people to participate in the mainstream, and to deny special needs or difference.

He says that both sides of politics have looked to minimising the political risks they take in the management of Indigenous Affairs by downplaying expectations and refusing to take responsibility for results. So where to now for the ALP?

Evans says that that means the ALP

"...abandoning our sense of misplaced moral superiority; acknowledging that the rights agenda is only part of the solution; accepting that confronting problems plague many Indigenous communities; and becoming more focussed on outcomes....Above all, the approach that Labor takes from here on will be driven by the evidence of what works and what does not. That must be our guiding principle. Labor wants to be driven by what is successful in reducing Indigenous disadvantage. To succeed we will need to look beyond our ideology and look to the evidence. "

So where does that lead? To the policies of Noel Pearson:

One area where Labor must engage more and adopt a less ideological stance is in the welfare debate. Noel Pearson's contributions on economic development, welfare dependency and individual responsibility have fundamentally shifted the Indigenous debate. His contributions have been more powerful because they are made by an articulate and passionate Indigenous person... His approach and new "get tough" language have invoked considerable criticism and unease from many Indigenous people. The truth is his agenda pushes the debate to issues where many of us are not comfortable to go. His language has been chosen to win conservative support, but he does confront real and raw issues that challenge us all. Many on the left of politics have failed to respond, in part because it takes them into the territory of very difficult and negative aspects of Indigenous life.

Senator Evans adds that, though Noel Pearson's language has been chosen to win conservative support, he does confront real and raw issues that challenge us all. Evan's observation that many on the left of politics have failed to respond, in part because it takes them into the territory of very difficult and negative aspects of Indigenous life is suprising, as is the fact that many Indigenous leaders seem reluctant to publicly engage in part because of their nervousness about the media treatment of Noel's critics.

This is suprising because Pearsons' ideas are an adaption of the Third Way to

March 20, 2006

from state to nation

In Empire Hardt and Negri argue for a revamped Marxism in that they talk in terms of the transcendence of modern sovereignty…by the immanence of capital flows and their insistence on capitalist power as the major focus for resistance and political action. We can see this imperial corrosion of the state in the constraints placed on sovereignty in neo-liberal economic restructuring with the opening to international capital flows during the 1980s.This globalisation-induced upheaval is furthered witeh restructuring of industrial relations and the shift away from centralized bargaining to individual contracts.

But we have, contra Negri and Hardt, a reassertion of sovereignty vis-a-vis the refugee and the terrorist, rather than their thesis of the dissolution of sovereignty. This reassertion, which is associated with the demonisation of the Other, the Stranger, and their incarceration and punishment for simply being non-citizens, is part of the general apparatus of governmentality and biopower intrinsic to modern sovereignty.

Now this reassertion of sovereignty is associated with promises to provide Australians with a sense of security and 'home', appeals to the nation. So what do Hardt nad Negri say about the nation?

They say that:

The nation is a kind of ideological shortcut that attempts to free the concepts of sovereignty and modernity from the antagonism and crisis that define them. National sovereignty suspends the conflictual origins of modernity (when they are not definitively destroyed), and it closes the alternative paths within modernity that had refused to concede their powers to state authority. (p.95)

The conflictual orgins of modernity in Australia were the destruction of the indigenous peoples. Hardt and Negri then add:

The process of constructing the nation, which renewed the concept of sovereignty and gave it a new definition, quickly became in each and every historical context an ideological nightmare. The crisis of modernity, which is the contradictory co-presence of the multitude and a power that wants to reduce it to the rule of one----that is, the co-presence of a new productive set of free subjectivities and a disciplinary power that wants to exploit i----is not finally pacified or resolved by the concept of nation, any more than it was by the concept of sovereignty or state. The nation can only mask the crisis ideologically, displace it, and defer its power. (p. 97)

March 19, 2006

democratic rule: lessons from Tasmania

Democracy is a form of governance or rule is it not? in Australia it is commonly understood in minimalist terms: voters voting for a choice between different professional political elites, with the winning team running the state as managers and administrators for the next four years.

As the Tasmanian election indicates we assume that stability, continuity, order are due to exercise of authoritative control. At the start of the election campaign opinion polls showed the Tasmanian Greens poised to increase their vote and gain the balance of power in the parliament. Over the four weeks of the campaign up to half a millions dollars was spent on negative advertising directed against the Greens. The election theme was fear about minority government----'we must avoid hung parliaments and minority governments that depend on alliances to govern as they are unstable and unruly.' Rule as control over others is the buried assumption here.

In this article entitled 'Rule of the People: Arendt, Arche and Democracy' Patchen Markell says that:

To say that democracy is a form of rule, then, is just to say that it is one distinctive way of arranging the institutions and practices through which authoritative decisions aremade and executed in a polity. Of course, there has been fierce disagreement about what, exactly, makes rule democratic. For an early generation of state-centered political scientists, democratic rule meant government authorized by a sovereign people with a commonwill; for their pluralist critics, it referred to authoritative decisions generated by a process that balanced the competing interests of a multiplicity of groups ....For adherents of the so-called minimalist account of democracy, rule isdemocratic when people are able to choose their rulers in competitive elections;... for others, more intensive and direct forms of popular participation in government are required ...These and similar disagreements, however, are ultimately about who rules under this or that institutional arrangement: the thought that politics is at bottom a matter of ruling, and that ruling consists in the exercise of authoritative control, remains part of the taken-for-granted background against which these debates take place.

This highlights the paradox of democracy. On the one hand, there is the idea of popular sovereignty, in which the people jointly exercise control over their collective destiny. On the other hand, there is the idea of popular insurgency or rebelliousness in the face of the nearly overwhelming power of state and capital the people spontaneously shatter the bonds of established political forms. Liberal democracy seems to be torn between rule and novelty, order and change.

'Rule' in its ordinary sense means a power of command over others and so it hollows out human freedom. It implies, Arendt observed in The Human Condition the

"...notion that men can lawfully and politically live together only when some are entitled to command and the others forced to obey."

So we have liberal democracy as a form of masters (political elite ) and servants (citizens). What Arendt highlights is a set of background assumptions about the picture of rule as authoritative control with its hierarchical relations of command and obedience, that are held in common by those who see democracy as a structure of authoritative control, and by those who reject such regime oriented views of democracy in the name of unruliness or revolutionary insubordination. Stability requires subordination---that is the message from Tasmanian state election .

March 18, 2006

rethinking sovereignty

An article by Richard N. Haass on rethinking sovereignty. Sovereignty is understood as:

...the notion that states are the central actors on the world stage and that governments are essentially free to do what they want within their own territory but not within the territory of other states...

Haass says that this concept needs to be rethought. In what way? Some argue that globalization has rendered the concepts of state soverignty anachronistic. So we should drop the concept of sovereignty and buy into the idea of transnational governance in the form of a powerful imperial project on the part of the United States that seeks to develop a useful version of global (cosmopolitan) right to justify its self-interested interventions.

Haass says sovereignty needs to rethought in the sense that:

The goal should be to redefine sovereignty for the era of globalization, to find a balance between a world of fully sovereign states and an international system of either world government or anarchy. The basic idea of sovereignty, which still provides a useful constraint on violence between states, needs to be preserved. But the concept needs to be adapted to a world in which the main challenges to order come from what global forces do to states and what governments do to their citizens rather than from what states do to one another.

Good point. However, Haass makes no mention of the effects of empire. An empire that is not organised around the hegemony of a particular nation state, but which is more a decentred and deterritorializing apparatus of rule.

March 17, 2006

the end of history, the last man + two Americas

There is an interesting question and answer session between Francis Fukuyama and Bernard-Henri Levy over at The American Interest's web site on the relative merits of Levy's American Vertigo. Now I do like this statement from Fukyama on the significance of the rootlessness of American democracy and its conception of the endless frontier:

That was the real practical meaning of American democracy: Every individual could set their clock to year zero; they could be what they made of themselves and not what their parents and ancestors expected of them. Europeans often look down on Americans for their loss of memory, their rootlessness, and, true enough, this becomes a real defect when Americans fail to understand that the other peoples they encounter do not suffer from their particular form of liberation amnesia. But it has also been very important to the success of American democracy. It meant that the United States has been more open to people from very different places and cultures who were themselves interested in starting over in a place where no one could locate Yerevan or Pusan or Lublin on a map. Europeans, whatever their aspirations to create a Habermasian post-national identity, are still rooted in communities of blood and memory, where people remember their ancestors and are defined by their parents.

Nice. But heavens me, what has happened to the question of the "end of history," as being ultimately a sad and emotionally unsatisfying era, and the creature who emerges at the end --Nietzsche's concept of the 'last man'? The one for whom nothing matters, who has no great passion or commitment, who is unable to dream, and who merely earns his living and keeps warm.

Well, we have this:

This doesn't lead the American demos to a happy animality, but to a restlessness and an energy and a willingness to bend rules to get ahead. Americans are religious, far more so than Europeans, which means that they actually believe in things that exist beyond the body and its needs, even if it leads them to strange debates over things like intelligent design. The End of History and the Last Man ended with ruminations about the possibility that modern democracy would yield "men without chests", wedded to ever-increasing peace and prosperity. During the Clinton years, in our preoccupation with the NASDAQ and Monica Lewinsky, that seemed a fair conclusion. But on further reflection, it has seemed to me that America was not remotely in danger of becoming the home of the Hegelian last man. Now that the United States has launched two wars in the new millennium, it seems like an even less apt concern. The last man actually lives in Europe.

Oh? The end of history is liberal democracy is it not? Isn't that when the dialectic between two classes-- the Master and the Slave--- meet in a synthesis, in which both manage to live in peace together in liberal democracy. So why is not the "last man" not to be found in the USA?

Bernard-Henri Levy responds, after bashing Europe for its appalling "criminal inclinations" and cynical deals to preserve its interests.

He says:

one must also question the health of America's democratic culture. And here I'm no longer talking about Las Vegas or about the war in Iraq. And I'm not even talking about the sense of discomfort felt by America's friends throughout the world when they saw how it responded so little, so belatedly and so clumsily to press reports about the scandals of Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib. No, I'm talking about the rest---about everything else, in no particular order: religious fundamentalism; the return of isolationist movements, both Left and Right; the rise of a nationalism reminiscent on some occasions of the worst trends of European national chauvinism; the upsurge of communitarianism that would negate American spontaneity and energy; the threats posed by mass consumerism---see the Mall of the Americas in Minneapolis, for example---that weigh down the individual spirit; and America's new hyperamnesia, which denies the "particular form of amnesia" that you rightly said has made this country a great one.

Bernard-Henri Levy then introduces the idea of the two Americas:

I could go on, but basically, my concerns reduce to a simple question: What is the state of health of American democracy? You know what my answer is: that here, too, there are two Americas, two American cultures. And between these two cultures---the great one and the other one; between the one we both love and the one whose evil characters I constantly ran into during my trip; between the great democratic and universalist America that is open to all newcomers and the America of megachurches, of Texas arms bazaars, and of huge malls, that is the source and at the same time the consequence of what I called a "vertigo" (and where I'm quite close, incidentally, to seeing, unlike yourself, the triumph of what you called "the last man")--there is a ruthless battle whose outcome neither you nor I can predict. But do you share my concern, especially my worries about American "polarization"?

And so it goes. Tis worth a read.

March 16, 2006

Empire + sovereignty

I've found another online text of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri's popular and influential Empire (Harvard, 2000). The digital text that I'd initially found, and was using nearly two years, has disappeared into the void. In the meantime I've bought the book. This makes it much easier to read and work through the text. I was at a distinct disadvantage before.

If you recall, Empire is a particular expression of an interpretation of the process of globalization, which held that the increasing integration of economies and markets collapses national borders and lead to the extinction of national sovereignty. "Globalisation" and the "new world order" would usher in a planetary "rule of law" through multilateral institutions such as the U.N., WTO, and other means of harmonisation and international governance. Neo-liberal globalisation does tend to deconstruct the boundaries of the nation-state to further the processes of the world market.

I found Hardt and Negri's account of a new global apparatus of rule---Empire--- suggestive. Hardt and Negri capture the juridical and political contours of this new imperium without borders, and their text explores the decay or the hollowing out of the idea, and formation of, sovereignty in modernity. Part 2 of Empire is entitled 'Passages of Sovereignty' with the first section (2.1, p. 69) called 'Two Europes, Two Modernities. In this section Hardt and Negri argue that:

Modern sovereignty is a European concept in the sense that it developed primarily in Europe in coordination with the evolution of modernity itself. The concept functioned as the cornerstone of the construction of Eurocentrism. Although modern sovereignty emanated from Europe, however, it was born and developed in large part through Europe's relationship with its outside, and particularly through its colonial project and the resistance of the colonizedModern sovereignty emerged, then, as the concept of European reaction and European domination both within and outside its borders. They are two coextensive and complementary faces of one development: rule within Europe and European rule over the world.. (p.70)

Their genealogy of modernity, which establishes the conditions of possibility' of modern sovereignty, says that European modernity has three moments:

its birth in the humanist Renaissance.This was revolutionary in that the old fedual order was toppled, the process destroys the relations with the past and a new mode of world and life is instituted;

the second moment of modernity is crisis: the Reformation was constructed to wage war against the new forces, establish an overarching power to dominate them and re-establsih ideologies of command and authority;

the third moment is the partial and temporary resolution of this crisis in the formation of the modern state as a locus of sovereignty. This unfolded in the centuries of the Enlightenment and crowns the transcendental principle as the apex of European modernity.

What this account highlights is that modernity is not a singular process but is profoundly split: between 'a radical revolutionary process' and an ordering 'counter-revolution' that 'sought to dominate and expropriate the force of the emerging movements and dynamics'.

What is this transcendent principle? Well it's not God. What they do is trace on path to the crisis of modernity that leads to the development of the modern sovereign state. Another pathway is the one to the nation, which presupposes the path to the state.

Hardt and Negri say that the transcendent principle can be found in the political machinery created in modernity:

The center of the problem of modernity was thus demonstrated in political philosophy, and here was where the new form of mediation found its most adequate response to the revolutionary forms of immanence: a transcendent political apparatus. (p.83)

This transcendent political apparatus is explored through a quick tour of Hobbes and Rousseau, with this judgement being made:

Hobbes and Rousseau really only repeat the paradox that Jean Bodin had already defined conceptually in the second half of the sixteenth century. Sovereignty can properly be said to exist only in monarchy, because only one can be sovereign. If two or three or many were to rule, there would be no sovereignty, because the sovereign cannot be subject to the rule of others.. Democratic, plural, or popular political forms might be declared, but modern sovereignty really has only one political figure: a single transcendent power. (p.85)

They go on to argue that the content that fills and sustains the form of sovereign authority is represented by capitalist development and the affirmation of market as the foundation of the values of social reproduction. Hence European modernity is inseparable from capitalism.

But we knew that already. So what is new? Their view that sovereignty becomes a poltical machine that rules across the entire society whose workings bring the multitude into an ordered totality though the general economy of administrative discipline (Weber) that runs through, and delves deeply into society; with these disciplinary processes or political machinery (Foucault) reconfiguring themselves as apparatuses that shape the reproduction of the population.

Modern sovereignty is not simply an abstract locus of juridical authority that forms the basis for Westphalian international law and order amongst nation states. It is a complex disciplinary and ontological machinery of enormous depth and force which functions to harness and control the possibility of freedom within capitalist modernity.The realization of modern sovereignty is the birth of biopower is their argument of this sketch.

This account holds that sovereignty, as it was imagined within modernity and tied to the bounded territorial authority of the nation-state, is in decline; and there emerges a new - supranational and deterritorialising - or imperial form of sovereignty. Though this new form of sovereignty is still repressive and disabling it also forms the terrain of a new mode of critical and revolutionary action - the terrain of 'Empire' and the revolution of the 'multitude'. Hence Hardt and Negri talk in terms of the revolution after modernity, the formation of new subjectivities, desires and antagonisms to domination. A new season opens:

As modernity declines, a new season is opened, and here we find again that dramatic antithesis that was at the origins and basis of modernity…The synthesis between the development of productive forces and relations of domination seems once again precarious and improbable. The desires of the multitude and its antagonism to every form of domination drive it to divest itself once again of the processes of legitimation that support the sovereign power…Is this the coming of a new human power? (p. 90)

March 15, 2006

Bush's 'state of exception'

I though that 'the state of exception' as a state of emergency that suspends the law was an idea that belonged to the rarified world of political theoriests, such as Carl Schmitt and Giorgio Agamben. Yet here we have it being openly discussed in the US by Mark Danner over at TomDispatch in the context of 9/11.

Danner says:

When you look at the record, the phrase I come back to, not only about interrogation but the many other steps that constitute the Bush state of exception, state of emergency, since 9/11 is "take the gloves off." The interesting thing about that phrase is the implication that before we had the gloves on, that the laws and principles that constitute our belief not only in democracy but in human rights left the country vulnerable. The U.S. adherence to the Geneva Convention, the U.S. record of treating prisoners humanely that goes back to George Washington, laws like the FISA law passed to restrict the government's power to surveil its citizens -- all of these constitute the gloves on American power and 9/11 signaled to those in power that the system with "the gloves on" was insufficient to protect Americans. That seems to be their belief.

Danner adds that the federal statutes against torture by the U.S represented restrictions that would hobble the the USA in fighting the war on terror and, by extension, threaten[ed] the existence of the United States. So they had to be removed. Hence torture -- now termed "extreme interrogation" -- goes to the heart of the reaction against the way this country has observed human rights in the past, a reaction in a way against law itself. This represents a conflict between legality and power.

Danner adds something interesting--- the state of exception is becoming the normal. He says:

In what I've started to call Bush's state of exception, we've now reached the second stage. Many of these steps, including extreme interrogation, eavesdropping, arresting aliens -- one could go down a list -- were taken in relative or complete secrecy. Gradually, they have come into the light, becoming matters of political disputation; and, insofar as the administration's political antagonists have failed to overturn them, they have also become matters of accepted practice, which is where I think we are now.

Danner says that the President claims that his wartime powers give him carte blanche to break the law in any sphere where he decides national security is involved.

So where is the countervailing power after 9/11tot he dominant executive that has supended the law? Danner says it lay in the June 2004 Supreme Court detention decisions. In one of them, Justice O'Connor declared that the President's power in wartime was not a blank check. Now, she's been replaced by Samuel Alito, an admitted defender in a "unitary executive", who when he was at the Justice Department, strongly pushed the strategy of presidential signing statements as a way to mitigate congressional assertions of power.

March 14, 2006

between civil society and the state

A review of a book of critical essays on Hegel's conception of ethical life ---as the ongoing living practices of an actual ethical community--in The Philosophy of Right. Ethical life is crucial in Hegel's political philosophy, as this category mediates between between civil society 's particular interests and the state 's universality. It is the category of ethical life that makes sense of the initial steps amongst those on the left of ALP taking the first steps beyond life lived within the market economy to link to concerns about mutuality, community, or social solidarity.

Hegel's distinction between civil society and the state evokes, and reworks, the civic republican themes of the primacy of the political, the primacy of the public to the private and the primacy of the citizen to the bourgeois; a reworking based on the human freedom. and the shift from the subjective freedom in civil society to the substantive freedom of the state. It is a distinction displaced by liberalism, it remains content with the subjective freedom within the boundaries of civil society.

Liberalism makes the freedom of the individual in civil society paramount; hence it is higher than the bonding or community in the family or the state. The family and the state are seen to constrain individual freedom in the name of the good of the family as a unit, or the common good of citizens in the state.

March 13, 2006

the death of social democracy?

It should be more about the renewal of social democracy, shouldn't it? But the factions are no longer concerned with a contest of ideas. If it cannot be carried out through the factions, where in the party can this debate about renewal occur? On its margins?

Clive Hamilton has a go at addressing the issue of renewal. He argues that an incipient recognition that the old model (statism?, welfarism?, the distribution of wealth?, the traditional deprivation model of social democracy?, egalitarianism?) can no longer serve the interests of the party or the nation.

The new thinking that is being opened is based on the realization that though we live in a nation with record levels of financial growth and prosperity, we alao live with record levels of discontent and public angst. We are on a treadmill of work; sense the lack of solidarity; find consumption as the reward for work disatisfying; yearn for community etc. Wasn't the Third Way meant to be all about this? Hamilton argued in Growth Fetish that most Australians want to turn their backs on material wealth.

Hamilton says that:

...there is an air of unreality about the debate over factionalism. The problem is characterised as a purely institutional one. The debate is wholly inward-looking, as if the problem lies solely with a handful of power-hungry factional bosses who have managed to capture the party. The structural problems are rarely debated in historical terms, so no one asks what has been happening in Australian society that has allowed the ALP to be transformed from a party built around a powerful set of values and social goals into one dominated by personal fiefdoms.

Hamilton adds:

The problems of the party structure are manifestations of a wider malaise - ideological convergence, individualisation in society, the withdrawal from politics and the withering away of solidarity. The party that evolved to represent the interests of trade unionists and their families cannot survive in a world where union membership has shrunk to less than a quarter of the workforce and where those who remain have been depoliticised.The Labor Party has served its historical purpose and will wither and die as the progressive force of Australian politics.

It's an accurate diagnosis.

March 12, 2006

multitude as democracy

I mentioned in the previous post that Hardt and Negri had argued that the form of globalisation they sketched in Empire requires us to think of new forms of democracy that can expand rule by the people to the transnational level.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri's Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire (2005) re-imagines the proletariat as a heterogeneous web of workers, migrants, social movements, and non-governmental organisations - "potentially ... all the diverse figures of social production", "the living alternative that grows within Empire."

The basic idea is as follows. The multitude is not " the people," but rather many peoples acting in networked concert. Because of its plurality, its "innumerable internal differences", the multitude contains the genus of true democracy. At the same time, the multitude's ability to communicate and collaborate - often through the very capitalist networks that oppress it - allows it to produce a common body of knowledge and ideas ("the common") that can serve as a platform for democratic resistance to Empire.

The second basic idea is the mode of political organisation embraced by the multitude. In place of "centralised forms of revolutionary dictatorship and command," the multitude organises resistance to globalisation through networks, which substitute "collaborative relationships" for hierarchical authority. Revolution from below is by a movement that can marry the spontaneity of anarchy with the power of mass resistance. Woodstock meets the Internet.

Is that not Seattle's 1999 moment for radical global civil society in the march against MacDonalds and the World Bank? The many seemingly different and independent struggles throughout the world are actually linked because as capital becomes more and more widespread, the struggles are objectively anti-capitalist.

March 11, 2006

Empire as globlization

Duke University literary professor Michael Hardt and Italian radical Antonio Negri's exuberant Empire (2000) described and analyzed the ways in which the global order has changed. Out goes national sovereignty, in comes supranational governance, controlled by a network of economic (IMF), political (the United Nations), and military (American) interests, whose biopower affects all of the Earth's billions.

Empire recast Marx's bourgeoisie as a placeless, faceless network of transnational corporations, international organisations, and the nation-states that benefit from them. In contrast to the old system of imperialism, real power, they argued, was now located in the transnational network of global capitalism. Though this network sometimes relied on states to accomplish its goals, it - not states - was the chief driver of change.

The Twin Towers symbolised everything Empire discussed. From the earth-encompassing power of finance capital, to internet capitalism's connection and compression of space and time, and to the cosmopolitan nature of the workers there, the towers were the epitome of everything Empire loved and hated about the world today.

This form of globalisation, Hardt and Negri argued, requires us to think of new forms of democracy that can expand rule by the people to the transnational level.

My initial response to Empire was two fold. Firstly, the flows of globalisation also worked to strengthen the position of the dominant states, perhaps changing the form of imperialism but not its effects-- I was thinking of the war on terrorism. Now I'm not so sure, as I begin to appreciate the way the security system is a network that uses various nation states.

Secondly, I couild not accept that religion and nationalism could be easily consigned to the historical dustbin that weas much beloved by international Marxists, and the neo liberal lovers of the revolutionary power of global capital. It struck me that religion and nationalism were actually strengthened by the effects of the libertarian flows of desire and capital (globalization) throughout the later 1990s and the early 21st century. Srtrengthened in a backlash sense.

March 10, 2006

violent democracy

Mathew Sharpe reviews Daniel Ross' Violent Democracy.

Sharpe says that Ross brings resources from the traditions in continental European thinking to the contemporary Australian political debates around the rise and fall of One Nation, the docklands struggle of 1998, East Timor, the Republican debate and referendum, the events of 2001--Tampa, children overboard, and 11 September---followed by the 'war on terror' prosecuted in Afghanistan, Iraq, and on the 'home front' in terms of markedly changed political rhetoric, and legislation that challenges existing liberal divisions of power.

Sharpe says that:

...these continental resources are usually disregarded--when they are not dismissed---in the Australian public sphere....The fact that Violent Democracy brings theoretical resources usually simply ignored in Australia is surely an overwhelmingly positive thing, especially in today's climate where more and more the 'new conservatives' and their spokespersons position the humanities academy as hopelessly 'out of touch' and 'elitist'.... By doing so, Ross' book invites a wider, non-philosophical audience to raise far-reaching and deeper questions about the nature of politics. In particular, as Violent Democracy's title suggests, Ross's concern is with how and why our political life always seemingly involves violence, whether this is inevitable, and what can and ought to be done about it.

So we have the violent heart of democracy--a theme argued in this weblog with respect to the work of Giorgio Agamben, with the camp signifying the violent heart. That's about as far as I've got. Sharpe says:

Violent Democracy runs two arguments about democracy's "violent heart". The first argument is that "the origin and heart of democracy is essentially violent". The book's second contention is that "the violence of democracy has changed, or is unfolding in a certain direction, across the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries."

My interest is the second contention as I accept the first. Australian liberal democracy was founded on the destruction of the indigenous population. The historical proclamation which announced that "we the people are sovereign" at federation in 1901 excluded the indigenous population.

So what does Ross say about the second contention---that the violence of

democracy has changed, or is unfolding in a certain direction, across the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries.

Ross says that even on its own terms, democracy has reserved the right to resort to violent action, that it has claimed a monopoly on the "legitimate" use of violent means, with the legitimacy of this monopoly being dependent upon the assertion of just ends. However, things have started with the endless War on Terror. Ross describes the change thus:

Violent means were always relative to and justified on the grounds of democratic ends, even when democracy perpetrated deadly violence. With the advent of the War on Terror comes a reorganization of these concepts, a shift away from democratic ends, and towards the self-justification of violent means. In the concept and reality of terrorism those states that refer to themselves as democracies are discovering a new potentiality for violence and are resolutely and confidently granting themselves a new right to act on it. Democratic states are re-assessing the situation of the world, with conclusions that affect democracy more profoundly than did the great wars of the twentieth century.

The new situation, signified by the War of Terrorism, is one in which the sovereignty of individual states becomes less important than a coordinated and integrated system of "security"--a system that I have been calling up the national security state. Ross takes this further by suggesting that this security system involves the creation of planetary security arrangements that transcends any particular nation-state. He illustrates it well in the book:

Ross remarks:

The notion that one could be lifted from the nation of which one is a citizen by the military of another, taken to a third country and imprisoned, without sentence, without trial, without charge, and without law, yet indefinitely, and with the very real possibility of execution at some indeterminate point in the future, all in the name of freedom, is a significant challenge to all existing legal and political thought. [p.142]

By interpreting the security system as within a nation-state I've missed the system across nation states.

Ross offers a chart of the new terrain in which liberal democracy is being transformed or undermined:

In the new state of democracy, old authoritarian tendencies are transformed into new ways and means, new laws and powers, new techniques of surveillance and control, new spaces and forms of imprisonment or homicide, that redefine the essence of the state itself. The state ceases to be the form through which the citizenry freely and politically, singly and collectively, make their lives. It becomes, rather, one mechanism within the overall system dedicated to the security and survival of the populace.

This is a significant change: one marked by a biopolitics that is not superseding or undermining the power of the sovereign.

March 9, 2006

renewing social democracy

It's the big project isn't it, working out how to renew the social democratic project in a globlised world.

Australia's economic and political base has been transformed in the last two decades and the future of the ALP is far from assured. We have the rise of a middle class politics of my/me which is structured on being fearful, a desire to keep the home safe, and downward envy. As long as the economy is strong they will vote Liberal. As Mark Latham observed they have contracted out economic management to the conservative Coaliton in federal elections, but they trust State Labor with their health and education.

So far the federal ALP hasn't done a good job of policy renewal whilst its been in opposition for the last decade. Mark Latham gave it a good shot whilst he was in the Shadow Ministry with education and then leader with his prosperity with purpose, but the ALP Right would have none of it. The machine men loathed Latham. They had no time for the enabling state. What they desire is a Leader who plays the machine game so they can run the show from a distance.

So here's one renewal option:

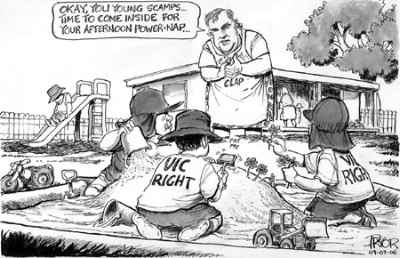

Geoff Pryor

It's the factional pathway that decides who is to be in the Shadow Ministry and merit is the last thing to consider. Its about flexing muscle, payback, and finding those who please their factional warlords. The machine men have no structured thoughts about making society better. They rely on polling and focus groups for policy direction and what they cannot control they destroy.

Here's another option: the path of policy renewal. Lindsay Tanner, who aspired to be Shadow Treasurer, after the 2004 federal election defeat, talks about the changing role of the liberal state in a period or rising prosperity at the CIS

What does he say? He says:

It's easy to overlook the impact of rising living standards, and base our expectations of government on a society which no longer exists. The state's role is changing. Our thinking needs to change too. The size of government is no longer the big issue. What governments actually do is changing. The emphasis is shifting from building to learning, from regulating to persuading, and from alleviating producer risks to moderating family income changes. Modern western societies are capitalist-socialist hybrids...Traditionally, left-wing parties have sought to expand the role of government and right-wing parties have resisted. The onus shifted in the 1980s and 1990s. Right-wing parties now seek to reduce the role of government, and left-wing parties usually resist. Yet while the battle between public and private continues, the relative balance between the two hasn't changed much for some time. The Howard Government has not reduced the role of government, but merely reshaped it to support its own political objectives.

He's right about that. It means that we to need to rethink the role of the state in light of the fundamental changes in our society over recent decades. What then is Tanner's suggestion, given that the ALP lost the support of the winners in the new economy ---those economic free agents, the contractors and consultants who just want the government to get out the way?

He outlines the current change to the state:

The Snowy Mountains scheme is a great example of the old role of government in Australia. The Bracks Government's decision to sell its shares in Snowy Hydro and use the proceeds to upgrade Victorian schools symbolises the change that's occurring. Governments' responsibility to ensure that all Australians can develop their capabilities is now more important than their responsibility to build things. The rapid acceleration in the need for learning over the past fifty years has pushed education to the centre of government activity. When most people did not finish school and few attended university, the burden on government was limited. The need for more skilled workers has grown rapidly since then, and changed the role of government in its wake.

We have the learning state. Which means what?

March 8, 2006

ALP -rotten to the core

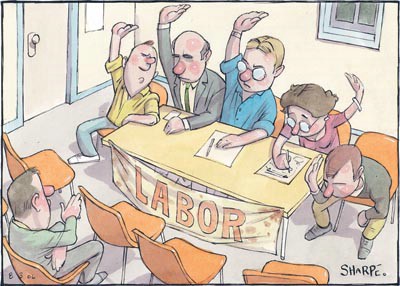

Julia Gillard in her 'Courage, Convictions and the Community' speech given at the Sydney Institute puts her finger on a key problem faced by social democrat parties when they are in opposition:

Before you can persuade Australians of your credentials to run the country, you have to show that you can run your political party. And to do that, we must unshackle our party from factions. It's time to stop mincing words and acknowledge that factionalism in the Labor Party is out of control and destructive. We are no longer talking about factionalism, we are talking about fractionalism.

I would say that the system is still fundamentally rotten, but that's the way the factional warlords want it, as it keeps them in power. So it will stay rotten from some time. Will the Opposition Leader confront rampant factionalism?

Sharpe

Jack Waterford, wriitng in the Canberra Times succinctly describes how the facitonal rottenness works:

The system is structurally rotten, not only because of the entrenched vote of trade unions in the party's councils, but because ALP rules allow the direction of those bloc votes to be in the hands of union officials, who make them without reference to their union members. That had nothing, as such, to do with the Crean victory, which was among eligible registered party members - but it could well have had, except for the fact that the Crean challenger faced up to his devastating branch-level defeat and withdrew from the contest. Otherwise there was still a possibility that a Crean endorsed by his branch members could still have been knocked off by the party's state central committee, which is essentially the creature of union heavyweights.

Waterford goes onto say that the smallness of the membership base of the ALP suits some factional warlords well:

The smaller the sub-branch, the fewer members are needed for a "stack". The more complete a stack, of course, the less necessary it is to even have the formality of branch meetings, given that a diligent secretary can simply concoct a set of minutes and a roll-call - rather like the overwhelming proportion of board meetings of proprietary companies...The [stack] process now has brokers, and votes are bought and sold.

The factional warlords are not going to want reform the system. That means the factional politics will remain a conflict about personalities, and combinations to share the spoils of politics and not a genuine contest about ideas and the best policies and programs and about how power could be best is exercised for the community good. Gillard concurs to the extent that lshe argues that the labels Left and Right on Labor factions are now without meaning.

Waterford goes to say that the ALP left has long abandoned its old role of being the engine-room of new ideas. He adds that there is a good argument that the true source of ideas in Labor at the moment is from the Liberal side of politics, after being played with by political professionals. That is what it looks like to me.

He then concludes on a future note:

The moribund general membership structure, and the thoroughly corrupted state-branch structures, serve not only to put real powers of patronage and dispensation in the hands of unattractive moral and intellectual vacuums. It also means that the party's kindergarten for its future leaders comes not from argument, debate and involvement in community affairs, but from attachment to faction leaders, demonstrated, of course, by unfailing loyalty. Increasingly Labor representatives are distinguished by having worked all of their lives as paid operatives of political or industrial labour

The task of reform is a big one.

March 7, 2006

Opposition politics feels like dogshit on the boot of democracy

So the factions are rolled back for the moment:

Geoff Pryor

Crean has come out fighting, calling for a massive cultural change in the Labor Party that involves an end to factional infighting, a call for Senator Conroy's sacking and a different style of leadership from Beazley. Crean appears to by invigorated by the preselection battle he has just won, he's really angry at how he has been treated by the Right faction, and looks to be deadly serious about taking it the factional warlords he holds responsible.

The latter became Crean's enemies when he pushed through reforms by trying to reduce the unions representation in party forums from 60 per cent to 50per cent, and to push through a set of rule changes designed to nobble the branch-stackers.The Right factional warlords wanted payback.

Crean is sounding very much like Mark Latham these days as he calls upon Beazley to develop more policy differentiation.

What is the Beazley style of leadership in opposition? Mark Lathan offers a succinct description in the Latham Diaries in May 27 2006, just after the ruins of the federal election:

Beazley tells the Shadow Ministry that 'Opposition is all about pissing on them and pissing off---a hit-and-run style of politics. He sees our political recovery as hinging on the exploitation of the Government's failings and public discontent, issue by issue. I've got a sinking feeling that Kim, for all his rhetoric, is not going to deliver a new modern Labor agenda. That's his philosophy: piss on them and piss off. (p.48)Latham comments that this strategy will never suffice as a political party in opposition needs a 'philosophy of government, a set of ideas that inspires our supporters and gives the show some purpose beyond an opportunistic grab for power.'

The factional warlords are just about a opportunistic grab for power offering a tinkering around the edges of past policy, or that of the enemy. The low target strategy by default.