July 31, 2003

Bill Henson#1

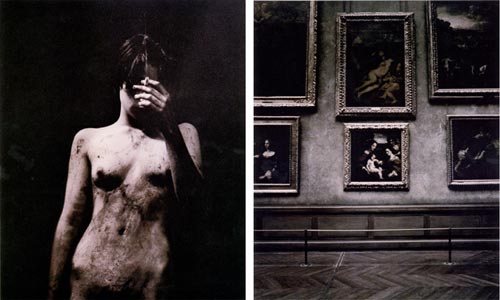

The Australian artist Bill Henson is commonly seen by the art institution as a passionate photographer of twilight zones: of the ambiguous spaces that exist between day and night, nature and civilization, youth and adulthood, male and female, light and dark.

His work does make me uneasy, despite the framing of the beautiful as a sexualised body. I find it disturbing, though not sensational. I cannot quite put my finger on why it is disturbing. Maybe it has to do with the passivity of the desiring female body? Why is she not calling the shots? Or has it more to do with the sexual desire of young kids? Why cannot 14 year olds have sex?

The unease goes back well over a decade:

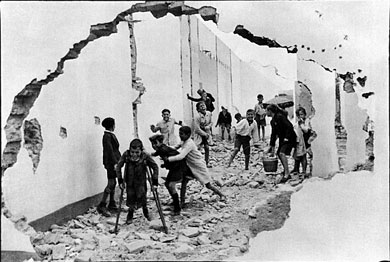

Street kids juxtaposed to high European art. Easy to get, as is the juxtapostion of poverty and wealth. Yet the image is still disturbing in a different kind of way to the more sexual image above. In what way is it disturbing though?

Is it the indifference of the art institution to the condition of street kids that is disturbing? Is it the teenager's sullenness and angst tinged with melancholy amidst the beauty, youth and romance?

Or has it to do with the visionary romantic artist in a post-industrial age continuing the tradition of photographers pushing the boundaries of photography as fine art? That is more cliched than disturbing in these postmodern times. Maybe it is the romantic artist who puts the finger on what is disturbing in our civilization?

This text gives a brief overview of Henson's work. He was able to move photography out of its ghetto in specialist photography galleries into the broader art world. He is an artist not just a photographer.

The strength of Henson's work is that it generates more questions than answers. That is the appeal. The questions disclose what we find disturbing, and we struggle to put our finger on it and then to express it. It is the disturbing quality arising from the questioning that makes it art and not porn.

Bill Henson , Untitled #58, Untitled, 1998 - 2000

The images refer more to our sense of being in the world than the play of light on man made structures and nature.

July 29, 2003

bob hope

Sad to see him go. I accept that he was a master of the comic monologue and the topical wisecrack--a drug store wit with roots in vaudeville.

But I had no warmth for his peculiarly American persona of the streetcorner smart arse.

I never really liked his work as a comedian. I detested sarcasm of the oneline wisecracks. I did respect his many tours of duty for US troops. And he did good work for charity.

I can acknowledge that he was very influential re the development of American comedy.

But I recoil from American comedy, eg. Seinfield or early Woody Allen. It leaves me cold. And I loathed the road movies. And as for Drew Carey and Steve Martin, juk.

Its a cultural thing I guess.

Of course, some would call it anti-American. Yeah. He was a Vietnam hawk who backed Richard M. Nixon and taunted protesters.

July 28, 2003

Sontag: Regarding the Pain of Others#10

The tenth part of Rick's project on Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others is concerned with the themes of beauty and shock. My comments on the ninth part of the project can be found here.

In this section Sontag says:

"It is one of the classic functions of photographs to improve the normal appearance of things…Beautyfying is one classic operation of the camera, and it tends to bleach out a moral response to what is shown."

Here is an example of the classical beautifying process of photography. It is portrait of a Tambul warrior from New Guinea. It was taken by Irving Penn.

Has the moral response been bleached out? Yes. Beauty is a historically product. The beauty in this photo is the beauty of fashion under the sign of art and Vogue. So we get an overlap between art and fashion in the form of style. Style is expressed though elegant lines and an elevated and aristocratic tone. Penn was a master of creating style as a spell of untarnished beauty.

When you put Vogue fashion and ethics together you come up with charity, the dictates of constant change in fashion or modesty. Still there is little point in banning beauty.

So let us accept Sontag's point about the beautifying process of photography. Sontag then turns to the opposite of the beautiful, the ugly. She says that:

"Uglifying, showing something at its worst, is a more modern function: didactic, it invites an active response. For photographs to accuse, and possibly to alter conduct, they must shock.” (Sontag, p. 81)

This bookwas once seen as ugly and shocking, then this. As Adorno puts it in Aesthetic Theory, "Ugliness is a historical and mediated category and when conservatives condemn such works as ugly they also mean decadent or corrupting. They tend to equate ugly with suffering.

And today? What photos do we find shocking today? This photo is considered shocking in the West. It is of Uday Hussein's body and it was publicly released to change conduct and opinion in Iraq:

Some do not find the photo shocking. Terry Teachout over at Arts Journal says the photos:

"...were broadcast on TV and scattered throughout cyberspace last week, usually labeled "warning—graphic photos," or words to that effect. And they were graphic, I guess…but I can’t say they shocked me. I’ve seen a lot worse (I used to work for the New York Daily News, after all). More to the point, the photos released by the Defense Department were tame compared to what you can see any day of the week by renting any reasonably violent Hollywood film released in the last 30 years or so, going all the way back to 1969 and Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch."

Others do find them shocking. Update. For the Arab world see here

And even some in the West. Why?

Because the public release of a photo of individual dead body breaks with an unwritten military convention not to publish photos of individual dead bodies. The US government explicitly broke that convention by releasing the photographs to prove to Iraqi's that Hussein's sons are dead.

As Photdude points out, this tradition of not publishing photos of individual dead bodies is codified in the First Geneva Convention.

Article 15 says: “At all times, and particularly after an engagement, Parties to the conflict shall, without delay, take all possible measures to search for and collect the wounded and sick, to protect them against pillage and ill-treatment, to ensure their adequate care, and to search for the dead and prevent their being despoiled.”

Article 17 states: “They shall further ensure that the dead are honourably interred, if possible according to the rites of the religion to which they belonged, that their graves are respected, grouped if possible according to the nationality of the deceased, properly maintained and marked so that they may always be found.”

Photodude says that though the Third Geneva Convention is specifically about prisoners of war, it does say they must be protected “against insults and public curiosity.” He adds that having your death-deformed face broadcast all over the world might just qualify as “public curiosity.”

In a latter post Photodude comes back to working out why he is shocked. He is shocked because basic human respect and international law has been broken.

So let us accept Sontag's point, that if photographs are to alter our conduct they must shock. Ths leaves us with tension of beauty bleaching out morality and the ugly shocking us. Sontag's duality is problematic.

Then Sontag adds something extra---some difference. She says:

“Harrowing photographs do not inevitably lose their power to shock. But they are not much help if the task is to understand. Narratives can make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.”

(Sontag, p. 89)

Below is a portrait of some plain country folk by Mike Disfarmer who worked as a photographer in Heber Springs Arkansas. The portraits that were taken from 1939 to 1946.

This photo is neither uglifying nor beautifying. It is haunting in its starkness and simplicity. Why haunting. Because the hard physical toil and suffering of rural Depression life is encoded in their bodies; as is their pride, stoicism and simplicity. Grief is expressed in these bodies--the photo expresses both grief and a sense of being alive.

The photos are also haunting because we understand that many of the portraits of country boys in uniform, with their mates and girlfriends just prior to them, will be going off to fight in WW11.The young men would be dead in a few years. The photo is a special event.

The young men would die in war. That is why these photos haunt us. They radiate a darkness that keeps beauty in check. The haunt us because they remind us of the affinity of art with death.

shopping malls

I've never been particularly fond of shopping malls. I felt trapped in them. I also intensely disliked the massive suburban ones, that were been built since the 1960s for the housing estates that were built far from the urban centre of the industrial city. I've more or less avoided the windowless warrens of chain stores that were scattered around a giant supermarket.

I have always preferred to do my shopping in markets where I could as the arcades in the inner city became a husk of their former selves and urban life atrophied.

So I was interested inthis piece about Victor Gruen, the Austrian architect who came up with idea of an enclosed shopping mall. It describes the design thinking behind shopping malls:

"As people left the cities for the suburbs of postwar America, what they missed was a central place for shopping, walking, meeting neighbors or just spending time. Highway strip malls were uninspired, dangerous and single-use. In designing the automobile-based environment, then, architects should restore some of the satisfactions of the old pedestrian city, with new climate control technologies, within the safe walls of a mall. "

Hence, the shopping center is one of the few new building types created in our times that provided a genuine and profitable alternative to downtown or strip shopping. The suburban malls elipsed the inner city, which pretty much died.

Victor Gruen has a dream. His innovative design envisioned the shopping mall to be a new town centre. It was to be a reinvention of the European public square. It would be the new centre in suburbia that would bring a vibrant community life to the motorized suburbs.

I never saw the dream realised myself.

suburbia

I have been writing a bit about the relationship between suburbia and the city. Since junk for code is becoming a more visually-orientated site I thought that I might upload some images of suburbia produced from someone living on the antipodean edge of the art world.

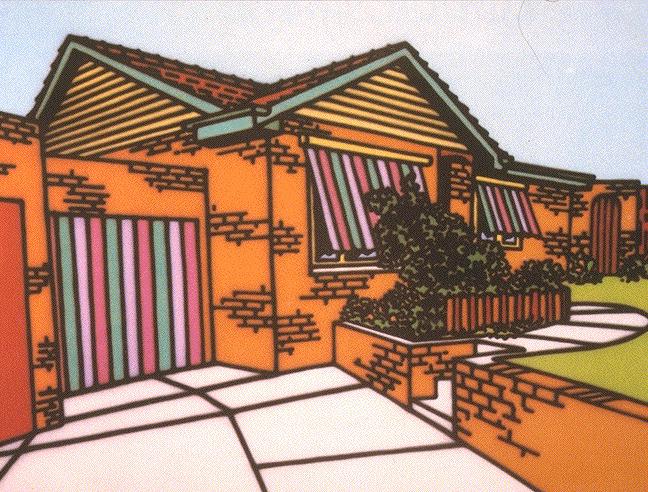

Here is a neon image of the exterior of Australian suburbia.

It is by Howard Arkley. Some information about the person as distinct from the painter is this text by the Melbourne writer Edwina Preston.

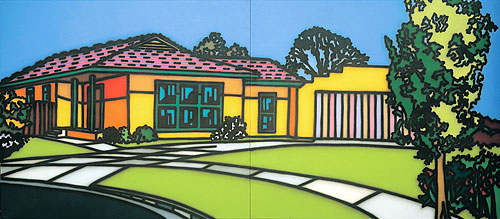

This Arkley's image of the suburban interior.

Suburbia is about house and garden, which is what makes it so different to innercity living.

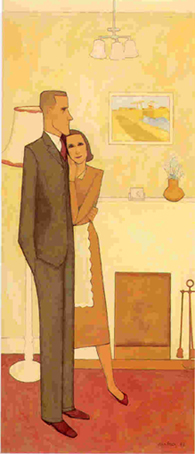

It is a different image of suburbia to that of the 1950s painted by John Bracks. In this representation, suburbia was an existential wasteland peopled by emotionally impoverished people living a life of soul-destroying conformity.

That one was prior to television and the endless flow of images from elsewhere in the world that would eventually work its way into our dreams and thoughts and so shape our desires. It was a world prior to pop.

However, Arkley's suburbia is not John Howard's white picket fence suburbia. This is Australia of the 1980s and so we have this ritual amongst the suburban boys:

It is a world corroded by the effects of heroin addiction.

However, I know little about the contemporary art world over the past three decades in which Howard Arkley worked. This review of Eddwin'a Preston's biography by the art critic John MacDonald gives us sardonic insight into the Melbourne art world that was theorized by the Art and Text crowd.

A more positive account is given by McKenzie Wark Television and pop gave birth to a new Australian aesthetic sensibility.

July 26, 2003

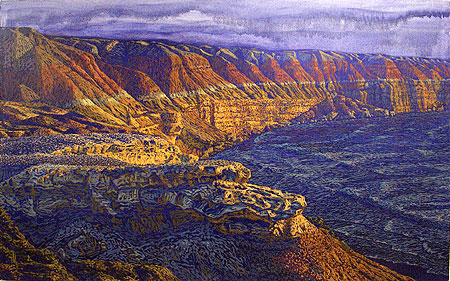

After an Exhibition: a note on Australian landscape

Regionalism in art---such as representations of the South Australian landscape have a hard time being accepted in the art world. This painting of Waldegrave Beach (near Elliston on the Eyre Peninsula) by Siv Grava--

Siv Grava, Waldegrave Beach, Images Gallery, 2003, Oil on canvas

This regional art is confronted by being rejected as unfashionable in the metropolis. The art institution still thinks in terms of avoiding the literal image, defying figurative conventions, the avant garde and being self-referential about art. They are still bound up in the prejudices of the New York avant garde of the 1950s, which held that regionalism was trashed by the march of art history. For modernists regionalism meant backward-looking conservatism whilst being avant grade meant being authentic.

Being modern for photgraphers in America and Europe meant this kind of abstraction:

It did not mean this:

That is Australiania or kitsch.

In a globalised world regionalism is returning. What causes its rejection this time is that it is about the specifics of place: eg., Maslin's Beach by Siv Grava

Siv Grava, Maslin's Beach, Images Gallery 2003, Oil on canvas

The opening of Siv's exhibition at Images Gallery was last night. I slipped in quickly whilst passing by.

So anyone producing works to represent the specifics of their place risks being ensnarred in Australianness, Australiania, and postcard views. Those words mean one thing to the art institution:---kitsch. Today, kitsch means artworks that appeal to popular or lowbrow taste, artworks that are often of poor quality, and cliched artworks. Kitsch causes that aesthetic 'yuk' feeling in the art institution.

And the reason for the immediate recoil, if not repugnance, by the art institution to the specifics of regionalism. Art transcends the particularities of place. It does so by either meditating on the [spirit] of the Great Southern Land, or alternatively by becoming a colouristic exercise of aesthetic appeal.

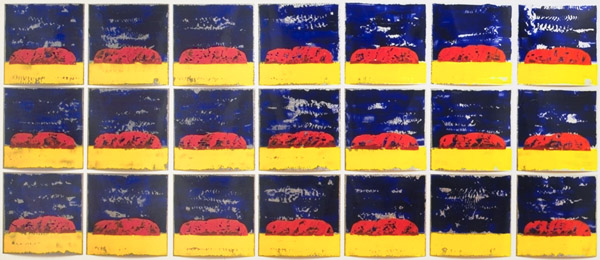

An acceptable strategy to avoid Australiania is to deconstruct kitsch sunset photgraphs of Uluru for tourists. Such a strategy is deployed by David Hume:

David Hume, Postcards From The Rock, Acrylic on galvanised steel, Beneath the Beyond 2 exhibition, 2000.

This strategy is seen as okay by the art institution because it is art being self-referential. Being self-referential means that the artwork is not a cliche, and it prevents the artwork from become part of the flotsam of mass culture. To be a good modernist you must fear and hate kitsch. For modernists art stands opposed to kitsch.

What happened with modernism was a forgetfulness about place. Place was erased. "Erasure" denote the art institution's tendency to displace, deny, or unrecognizably alter its past; its history of being in a specific place. The traces of the past continued to remain even after the landscapes and buildings had been demolished. What occured was a burial, rather than a disappearance of regional representations of the past and place.

We are now begining to recover the old images of our region:

The Hans Heyson representations of the Flinders Ranges, which were once high art, are in danger of becoming kitsch.

July 25, 2003

Sontag: Regarding the Pain of Others #9

The ninth part of Rick's project on Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others is concerned with the beautiful in relation to what I came to call in my last Sontag post about photography and ethical criticism as the problem of evil.

Should photographers express human suffering in terms of beautiful images? The argument that Sontag introduces holds that beautiful images of human suffering seem to trivalize suffering (evil) by taming it and making the evil disappear.

Sontag approaches this in terms of a duality. She plays off photography as art with photography outside the art institution, such as photojournalism. She says:

"Transforming is what art does, but photography that bears witness to the calamitous and the reprehensible is much criticized if it seems "aesthetic"; that is, too much like art....Photographs that depict suffering shouldn't be beautiful, as captions shouldn't moralize.

In this view, a beautiful photograph drains attention from the sobering subject and turns it toward the medium itself, thereby compromising the picture's status as a document....A photographer who specializes in world misery (including but not restricted to the effects of war) Sebastião Salgado, has been the principal target of the new campaign against the inauthenticity of the beautiful.” (Sontag, p.76-78)

I do not know the work of Sebastião Salgado, but he has an extensive body of work. You can see some of his recent work on migration here. (There are three galleries of photographs). And here is a critical review of his first Latin American work, Other America's (1986) and his second book on Latin America, Terra: Struggle of the landless (1997)

Clearly this work shows human suffering on a mass scale and it poses the problem of evil in terms of the intelligibility of the world. Why so much evil?

You look at these photos and ask, Why? Why this human suffering? Why so much suffering? The problem of evil is not something natural (eg., the Lisbon earthquake); or that it has something to do with God and the existence of evil in divine creation. What we understand from Salgado's photos is that suffering has been caused by other human beings----to the large scale forces and institutions that human beings create. Here photography is a long way from philosophy which is still caught up in escaping the theological past.

In trying to come to come to grips with suffering on a mass scale Auschwitz haunts us, as does the Gulag. We understand the machinery of death at work here.

Now Salgado's photographs are elegantly composed and he has a poetic eye. He is a first class image makers and an excellent black and white photographer. Hence the beautiful image:

Does the beauty of the image undercut the representation of suffering?

I personally find the claim that "photographs that depict suffering shouldn't be beautiful" an odd criticism. You rarely hear the argument that a well written piece of prose undermines the depiction of suffering; that well-written prose draws attention from the suffering subject and turns it toward the medium itself.

So why is a photography different. Why does a well composed photograph----as Salgado's are----compromise the picture's status as a document? Why does a well-composed photograph---ie., a beautiful photograph---draw attention away from the suffering subject and to the medium itself?

It is not obvious that it does.

The criticism that a formally balanced image undermines the representation of suffering implies that the aesthetic is about the beautiful---ie., it is a theory of the beautiful. If form is a part of the language of art ---its inner logic--then the criticism implies a formalist aesthetic and, further, that there is only a formalist aesthetic and such an aesthetic has no content. Thus art is about itself.

It is not just the case that there is a continuum in the different kinds of photojournalism between the poles of information and expression and that that traditional (proper) photojournalism is more concerned with information and its images are documents; whilst the more expressive photojournalism becomes a fine art photojournalism in which its images are often symbols.

Two quick comments. The aesthetic cannot be reduced to the beautiful. It is also about the representation of subjects considered ugly and the sublime.

This ignores that the form of the photograph expresses the content, eg., conveying the estrangement between people through formal structures through beams and shadows that separate individuals from one another; or windows and doors that divide people rather than enable communication between them; or gazes that cross a space but do not meet. The formal structures are the language of through which a documentary photograph expresses the content.

A well composed photograph expresses the content of homelessness better than a badly composed one--shapeless and lacking structure.

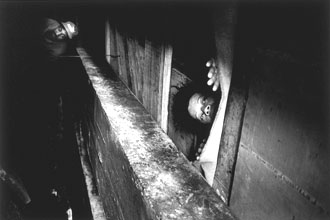

Moreover, the photograph does not stand alone as it is embedded in a narrative. The Migration work is about millions of people in motion, seeking survival and a better life -- leaving the land for the cities, living in refugee camps:

and then living in impoverished conditions in the cities.

The indicates that the individual photograph is placed within an interpretative framework that makes sense of the accumulated meaning of the series of phootgraphs by providing an articulated historical context for the reader.

humanised geometry

In the Australian Financial Review of all places (subscription only, Review, Friday 18 July) there is a long article on Henri Cartier-Bresson, the French photojournalist and cofounder of Magnum.

Cartier-Bresson's images are so well known:

that they have become a central part of our visual tradition and historical memory bank.

You can find the interview here in the form of a review of, Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Man, the Image and the World, by John Branville.

A private foundation has been organized, a new book produced, and there is a retrospective exhibition at the Bibliothèque National in Paris.

In the lunch interview the 95 year old Henri says that he has no current interest in photography. He had given up his decisive moment photography that once captured a fleeting reality in terms of humanized geometry for drawing around 1970.

This is understandable, for Cartier-Bresson had always seen the Leica as a sketchbook for the poetic eye coded for aesthetic balance.

The historical image is that of the genius phtographer wandering the world intuitively discovering photographs in the historical moment. Yet he was also a photojornalist who made his living through his photos of major events.

As he was a both a photojournalist and an artist

the phrase humanized geometry is apt. It is a poetics that affirms life

This poetics undercuts the dismissal of photography by Adorno in his Aesthetic Theory on the grounds that it is a form of copy realism that cannot account for the moment of critical opposition in art.

Adorno says very little about photography. It is limited to a few quips about the flaw of photography is that it is too attached to thing-likeness; and that photography tried to legitimate itself by clinging to the model of the portrait. It is not autonomous art as it was to tied to reality.

Photography was a different way of seeing.

That is what Cartier-Bresson showed. It was what Adorno ignored.

For Adorno Photography was a part of the culture industry. By and large this commodity's regressive side dominates, and it is part of the new social cement of the capitalist system, rather than helping to crack the cement of the culture industry.

July 23, 2003

Derek Allen Interview #7

This is the seventh and last part of Rick's interview with Derek Allen on Malraux's theory of art. It was the post that I lost on the weekend, much to my dismay.

In the interview Rick mentions that Derek has recently presented a paper entitled ‘André Malraux and the Function of Art’ to an aesthetics conference at Sydney University organized by the Sydney Society for Literature and Aesthetics.

The paper is not online. None of the conference papers are. Neither are the major academic journals online. Even though aesthetics has become rich and varied aesthetics remains a closed academic shop--an academic speciality. The exceptions are Contemporary Aesthetics and Canadian Aesthetic Journal There is still a lot of work to be done to overcome traditional aesthetics as an academic discipline and develop a critical theory of the image.

The topic of the interview is the function of art. Is there one function of art? asks Rick

Derek says that 'function' in his paper meant the creative act. However function also has a another meaning----the end of art practices. So what can be said about that.

Derek responds by highlighting the way that Malraux breaks with traditional aesthetics. He says that:

"..it is certainly true that, in Malraux’s view, the creative achievement that we today name ‘art’ has not always been directed to the same end. Indeed, he insists very strongly on this point. In Ancient Egypt, for example, as he points out, the concept ‘art’ was non-existent and the purpose of those objects from Egyptian culture that we now call art was, quite specifically, to promote the well-being of the departed in the Afterlife. That was their function, their very raison d’être. One can find many similar examples in other cultures."

Derek adds that:

"Malraux wants a theory of art that fully acknowledges this – a theory that does not try to fudge the issue by claiming that, irrespective of what they may have said or done, the Egyptians ‘really’ saw their Pharaoh’s image in his mortuary chapel as what we term ‘art’, or, as some try to argue, as an instance of ‘the beautiful’".

This is break away, or a rupture from traditional aesthetics. It represents an overcoming of aesthetics. Derek then adds:

"It is, to my mind, one of the key questions facing aesthetics today, and one to which it has so far failed to give a good response, or even to raise in clear, unambiguous terms. Malraux is seeking – and to my mind successfully finds – a theory of art that deals with this."

Rather than fudge the issue Adorno made some steps along these lines. He saw both art and science evolving out of magic with art aiming at mimesis. It is only a step because in Aesthetic Theory he mentions that:

"...the autonomy art gained after having freed itself from its earlier cult functions and its derivatives depended on the idea of humanity. As society becomes less humane art becomes less autonomous. Those constituent elements of art that were suffused with the ideal of humanity have lost their force." (p.1)

Hence the place and function of contemporary autonomous art has become uncertain.

So though art steps out of magic Adorno sees the cultural practices of Ancient Egypt in terms of the cult function of art or its derivatives. And again, when talkign about art's wound:

"Having disassociated itself from religion and its redemptive truths, art was able to flourish. Once secularized, however, art was condemned, for lack of any hope for a real alternative, to offer to the existing world a kind of solace that reinforced fetters autonomous art had wanted to shake off."(ibid, p. 2)

Adorno's main concern is with the function of autonomous modern art. When talking about the origins of art he mentions prehistoric art. So he sees art as changing, rather than art being born in a secular liberal society. But he gives it a twist that brings him close to Malraux:

"Works of art become what they are by negating their origin. It was only fairly recently, namely after art had become thoroughly secular and subject to a process of technological evolution and after secularization had taken hold, that art aquired another important feature: an inner logic of development." (ibid, p.4)

Art sees art as a process of becoming. he then says:

"Art should not be balmed for its one -time ignominous relation to magical abracadabra, human servitude and entertainment, for it has after all annihilated these dependences along with the memory of its fall from grace."

Malraux is much sharper. The concept ‘art’ was non-existent in Ancient Egypt and the purpose of those cultural objects from Egyptian culture are not art. I think that Walter Benjamin is more radical than Adorno on this and so is closer to Malraux.

to be continued.

modernist urbanism

I came across this phrase---modernist urbanism---and it caught my fancy. What does it mean?

traffic flows and freeways, skyscraper landscapes, garden city suburbs, inner city decay, the dominance of the car, the end of inner city urban life, the shopping mall as the mediator between the decay-of-the-inner-city and the rise-of-the-suburb and machine living.

It means shopping. department stores as a ladies delight. high art/mass culture split, the wealth of a nation as a ‘wealth of nations’ an immense accumulation of spectacle of consumer images. the expansion of desire.

junk space. lots of trash. human debris

airconditioning. paralysed historical imagination. a nightmare of being eternally trapped in a shopping mall.

In the end there is little else to do but shop’.

Modernist urbanism. A mode of urban life in decay.

July 22, 2003

corporate architecture

Lear's Shadow is a fantastic site. I came across it courtesy of wood s lot

This project called Discovery Walk in Kafkatown goes way beyond my few meagre insights into modernist architecture in Australia (here and here). It works with a very sophisticated account of modernist architecture and corporate power in Toronto.

In part one Douglas downplays place in favour of a modernist copying/emulating of the New York skyline in Toronto. He is right to do so. Being modern was being like New York in the second half of the twentieth century. If your city did not look like a cut down version of New York, then it was not modern. Hence Sydney was modern. It had the skyline. Adelaide is not modern. It has no skyline of note. It remains pre-modern.

And Douglas is quite right to suggest that the modernist, commercial office building (ie., the glass skyscraper) has surpassed the civic and religious architecture of our time in monumentality. As he writes:

'Mies [van der Rohe's] style sent the rectangles skyward, seeming both to signal and to reinforce the role of "the commercial" as the successor to religion, and even to civil society itself in North America.'

Toronto got its very own Mies Tower. That is prestige and status for Canadian capitalism. Sydney had to make do with its homegrown Harry Seidler. His roots were also in the rejection of decorative adornments, frivolous subjective trimmings and traditional built forms.

There is a refusal to compromise in the buildings built by these high modernist architects. But their corporate towers in the CBD do signify the projection of power on a massive scale. That is the historical truth this kind of art discloses.

I just cannot read this art work as being oppositional to society. As Douglas says its aesthetic rationality has more to do with homogeneity, hierarchy, and human beings as functional units of a larger, more significant corporate whole that functioned like a machine. That is the political function such buildings have in our society and they are experienced as oppressive forms in terms of the way they function in our lives.

This sort of ahistorical modernism should be dethroned as it's aesthetic brushes the past into the gutter as just so much rubbish; and its buildings fails to offer an alternative vision-- the last conceivable refuge for a different understanding of nature, culture and society to that embodied in the instrumental rationality of corporate Australia.

Sontag: Regarding the Pain of Others #8

The eighth part of Rick's project on Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others is centred around the large format photographs taken in the American civil war. The photographers Alexander Gardner and Timothy O'Sullivan are mentioned by Sontag though not Mathew Brady. Brady as a photographer-entrepreneur, organized Gardner and Sullivan, who were the core of Brady's Photographic Corps and were the makers of many of the well-known pictures.

In many ways the names are less important than the discursive space. For what we have entered into is what can be called a photographic archive: that repository or collection of nineteenth photographs over time that exists outside of the boundaries and tentacles of the art institution. The art historians mine the archive and reassemble bits and pieces within the modernist categories (genre, landscape, oeuvre, artist, work) that are previously constituted by art and history.

Bits of Timothy O'Sullivan's work has been so reassembled---within the aesthetic as fine art---- whilst his photographs in the achive that functioned as reportage, documentation, evidence, illustration and scientific information has been displaced. His landscapes (in the archive these photographs are called views) now serve to ensure photography's new found autonomy as an art form that can distinquish itself in its essential qualities from all other art forms.

The war photos are left in the archive--that set of practices, institutions, knowledges and and relationships ---to which nineteenth centry photography belonged have escaped the categories of the art museum which make photography a medium of subjectivity. Outside the art museum/gallery we can read the civil war photographs as a part of the American history they were a part of and signified. Reading here involves interpretation, interpreting the photographs that were originally organized into albums shaped as narratives with the help of written texts. Texts like Brady's Photographic Views of the War, plus Gardner's Photographic Sketchbook of the War and Barnard's Photographic Views of Sherman's Campaign functioned as contemporary histories, with the photographers working as historians.

The bit of Sontag's text that is montaged to the photos refers to the face: Sontag says:

"With our dead, there has always been a powerful interdiction against showing the naked face. The photographs of Gardner and O’Sullivan still shock because the Union and Confederate soldiers lie on their backs, with the faces of some clearly visible.” (Sontag, p.70)

What we see in some of these photos are not grand history celebrations of heroic actions; but depictions of rotting corpses, shattered trees and rocks, wounded soldiers and they depict the reality of violence, the effects of shells and bullets on flesh and bone. These are not just corposes; the bodies have faces and so are they individual human beings: someone's son, lover, husband or father. Here is a response to the images when they were first shown in New York. And another by Oliver Wendell Holmes

It is photography as historical documents, not painting, that lends a voice to human suffering. Painting was concerned with myth and the theatre of war.

The standard discussion to the sequence of war photographs has been around the truth of what they depicted, given that many of them were staged. But you do not need 'true representation' (as correspondence to reality) as a way to gain an understanding of ethics of these war photos.

The ethics arise from the images creating an aversion in its readers, due to the shock of war being waged on human flesh; an aversion because the readers found some of the images to be so repulsive, that they retreated to the language of martyrdom and redemption to bury the grim images. So we have the struggle of comprehension of what Walt Whitman called "a seething hell and black infernal backgrounds of countless minor scenes" in his Specimen Days.

I have highlighted language, representation, and the metaphysics of presence of these civil war photographs. Despite the textuality of these images/texts we have is the immediacy of the ethical response that conveys a sense of the urgency and complexity of ethical problems and is able to make contact with our own questions about our lives. What these images dramatize in a vivid way is how the images of mutilated human beings in the Iraqi war were not presented in the mass media. They were avoided, censored out. We had to go to find thembecause they were deemed to be too confronting.

We do not read these images as if they are a novel and so look for the ethically salient interactions of character and circumstance; nor do we read their intertextuality for a textually immanent ethic. Nor is the ethical encountered to lie in one's face-to-face encounter with the presence of another person. It is an ethics understood "through language"; an ethics that engages with what philosophers usually call the problem of evil as a way to make sense of the horrors in human history.

What Sontag has done counter the "fancy rhetoric" that downplays the reality of war and pretends that everything has turned into spectacle. She counters it by showing that at the heart of the issues concerning war photography and conscience there are real people, actually suffering.

Yet we should not speak of reality becoming a spectacle as breath-taking provincialism because the 1991 Iraq war was a spectacle on television: the fireworks lighting up the night sky over Baghdad is what we citizens were allowed to see by the US military. It was organized as a spectacle.

July 21, 2003

photographic criticism

Yesterday's post on photographic criticism picked up on some previous remarks about photographs being a part of the museum without walls, photography as a process of signification (or signifying practice) and photography between high art and popular culture. It tried to set the scene for part 8 of Rick's Sontag project.

What the post suggested was that if we are to understand photography's place in the world, then photographs need to understood as cultural messages; not as well or badly composed artistic images of the artist photographer engaged in a political fine art practice or documentary pictures of reality made by heroes and activists.

It then argued that photographic discourse can never be properly aesthetic and that it has borrowed the categories of aesthetic discourse (eg.,orginality, subjective expressiveness, formal unity, style and tradition, uniqueness of art object). That late modernist art discourse placed the emphasis on autonomy, purity, and self reflexivity of the work of art that was produced by promethean artist. That discourse, which evolved in New York with the abstract expressionists eventually shifted photography from being social documentary to a medium of privileged subjectivity, whilst accepting its mechanical mode of production.

There is an option to accepting Greenbergian formalism and then thinking of other kinds of photography as art corrupted by commerce, pictures of reality (eg., photojournalism) or kitsch. We can accept that we are surrounded by a world of images as signsand that we live among elaborate systems of images that feedback meaning through a network of images. These images often construct particular kinds of reality (eg., the freedom/bush bashing advertisements for 4 wheel drives) that then shape the way we view our life. From this perspective outisde of the art institution we can see that there are many diverse kinds of photography----aerial, medical, police, anthropological, advertising, family snap shots etc etc.

What is the implication? That a photograph has many different meanings depending on the context and use. Various institutions (the art institution, advertising) authorize certain meanings and dismiss others. Hence we have a politics of interpretation.

But that way of looking at photography leaves the ethics of interpreting photos graphs to one side; one that was traditionally associated with an ethics of narrative or story telling of a Eugene Smith. This kind of ethics is one in which we come to our sense of value in a particular narrative by experiencing them in context of others that are like and unlike them. We rely on our past experiences to make judgments and we confirm our judgement by making comparisons and through conversations with others.

testing testing testing

Due to the recent server changes at Movable Type----what the tech support notice says is the migrations of all ARTEMIS-based accounts to the new network operations----I lost all of yesterday's posts. There was a post on development and heritage along the southern coastline of Australia; one on the Derek Allen interview, one on Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of the Pain of Others and one on photography.

A full days work has gone down the tube. I'm deflated rather than rejuvenated. I will never be able to reproduce them.

I will endeavour to give summaries of them. A summary has been added to an earlier unfinished Sontag post.

July 18, 2003

Sontag: Regarding the Pain of Others#7

The seventh part of Rick's project on Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others is centred around Goya's suite of eighty-three etchings called the Disasters of War. These depict the atrocities committed by Napoleon's soldiers who invaded Spain in 1808 to quell the local insurrection against the imperial French rule of their country. As such they stand in opposition to the French paintings that glorified Napolean and celebrated the heroism of the French troops in the Peninsula War (1808-1813).

The text that Rick attaches is Sontag comments from her book. She says:

"Goya's art, like Dostoyevsky's, seems a turning point in the history of moral feelings and of sorrow -- as deep, as original, as demanding. With Goya, a new standard for responsiveness to suffering enters art." (Sontag, p.44-45)

Art and morality. How often they collide. This terrain is a minefield. A lot of it surrounds the issues of censorship and freedom of expression and many hold that asking art to serve a moral, or any other end except aesthetic quality, is to make an illegitimate demand on art. On the other side, there are those who see art as providing a form of moral education. The relationship between art and morality has been a frustrating debate historically, and it has preoccupied contemporary philosophers, such as Iris Murdoch.

By and large, ethical criticism is generally associated with literature and not the visual arts.

Sontag cuts through a lot of the confusion about ethics and art with the Goya suite of images of human suffering.

Update

The continuation of this post was lost due to the change of server at Movable Type.

The post was about the value of ethical criticism in relation to the ethical tensions in an image without embracing the literary humanist idea of particular sort of moral enlightenment as character-improvement, moral uplift and an aesthetic education that teaches us to become more compassionate toward the others.

This ethical criticism connects an ethical response to human suffering represented by Goya's image to eudaimonia or human flourishing. It is a rupture from the old Enlightenment/Romantic tradition in which a radical distinction is made by the scientific Enlightenment between an instrumental reason on the one hand and on the other hand emotion and imagination. The Romantics merely inverted this hierarchy. Instead of seeking to use reason to master and control feeling, they liberated feeling and imagination from the tyrannies of reason. They did so by disconnecting feeling and imagination from accountability to the public sphere and allowing them soar free. They wanted radical autonomy.

Goya's etchings reconnect art to the public sphere and reconnect feeling and imagination to reason---an ethical reason that talks about a particular historical event: the brutality fo the French occupation of Spain. Here the artist is inside the republic ---not banished as with Plato; nor celebrating their banishment as with the Romantics, who wanted freedom from anyone telling them what to do with their art.

What Goya points to is a robust critical public culture in which one is prepared to question authority in the name of morality that gives voice to human suffering, rests on respect for reason whilst appealing to human emotion.

Derek Allen Interview#6

This post picks up on the sixth part of Rick's interview with Derek Allen. In this part the issue of art's historicity is placed on the table.

Rick refers to this in terms of being ‘time-bound’, ‘subject to change and potential consignment to oblivion’, and he suggests that Derek regards this as ‘the most radical challenge Malraux represents to the way the art institution understands art.

At first this seems to be a bit over the top since German philosophy and aesthetics (Hegel & Nietzsche) in the nineteenth century went historicist in reaction to Kant. From this perspective it is modernist, Anglo-American analytic aesthetics that went formalist in the early twentieth century, and so repudiated the historical nature of art. Malraux could be interpreted as standing in the continental aesthetic tradition and reworking it ---as Adorno did.

Derek's reply is very informative. He refers to the dilemma in which aesthetics now finds itself where this question is concerned.

"On the one hand, we have the longstanding aesthetic tradition suggesting that great art is timeless or eternal. On other hand, there’s the powerful stream of thought originating with writers like Hegel and Taine, and carried forward by various post-Marxist writers (Eagleton is a well-known current example), that art, like all other aspects of human activity, is part of historical experience."

That's good. Derek then says:

Both theories, as we know, run into major problems... So we quickly reach an impasse."

It would be nice to know what the major problems of Adorno's Aesthetic Theory are, but we'll let it go. Derek then introduces the way Malraux deals with the question of art and time. He says:

"For Malraux, a work of art is by its very nature ‘born to metamorphosis’ as he puts it, whether its creator is aware of this or not....He is not dismissing the context in which the work of art comes into being. To that extent, the work does have ‘one foot in history’ so to speak – whether it be the world of an ancient civilisation or of a more recent period. But that, for Malraux, is only the work’s point of departure".

Then comes the key bit. From this point of departure the art work:

"...then sets out on its journey of metamorphosis – which may sometimes result in it being consigned to oblivion for long periods (as Egyptian art was for two millennia, for example) and at other times lead to its rebirth, though always in a different form – as the Pharaoh’s sacred image is now reborn as a ‘work of art’ for instance."

Well we can get that. The work produced by women disappear from history and were forgotten, until they were recovered by feminists as art in the 1970s and 1980s. The 1940s and 1950s work of Joy Hester in Australia comes to mind. (More works here.) The work of the French photographer Eugene Atget would be another example. Many of these were not considered art works when made.

But then Derek introduces the hard stuff:

"A key point to note, going back to the point from which I started out, is that the work of art for Malraux is neither eternal nor embedded in historical time. He is offering us an entirely new conception of the relationship between art and time."

How can that be? How can artworks be historical through and through and yet not embedded in history? Derek leaves it there for us to puzzle over. What can be made of it?

It's a hard one and I have not read Malraux.

One suggestion that can be made is Adorno's idea of autonomous art. It is historical and socially mediated but its autonomy enables it to mount crucial resistance. Hence its social significance.

Such art works belong to a society where exchange has become the dominant principle of social relationships. Like other commodities they hide the labor that has gone into making them, and they appear to have a life of their own. They appear to be superior cultual commodities that are detached from the conditions of their economic production. And they appear to serve no use beyond their own existence.

Adorno does a dialectical twist here to dig out the autonomous nature of art.

By appearing to have a life of their own works of art call into questrion a scociety where nothing is allowed to be itself and everything is subject to the principle of exchange. By appearing to be detached from the conditions of economic production, works of art acquire the capacity to suggest changed social conditions. And by appearing to be useless, works or art recall the human purposes of production that instrumental (economic) reason forgets.

Is that dialectical interplay between autonomy and social character a way of understanding Malraux's idea of art works being inside history but not embedded in it?

July 17, 2003

Tim Blair's big disgust

I see that Tim Blair has had another sneer at the masses at Adelaide's Festival of Ideas. The image he constructs is one of ideas festering. It seems that the smell from the putrid ideas offends him. No attempt is made to sift the ideas. What is putrid is the festival.

Tim Blair reminds me of the story of madman who runs into the marketplace with a fully lit lantern shouting, "have you heard, have you heard, the gravedigging masses are discussing ideas. Be warned, be warned, we will lose our culture."

The people stop their shopping for a moment, look around, pause, see the madman, then wonder what is going on. "Who is this madman?", they ask? "Why is he stirring things up?" Is he a fly of the marketplace?"

"Be warned", says the madman. "Darkness will soon fall. Space will bcome empty again. It will become colder. Can you not hear the noise of the gravdiggers in Adelaide burying our culture?"

The crowd laugh. "Have your lost your way, they ask? The asylum is that way. And they point to the disused abbatoirs called the Dollar Sweet.

The right wingers who read Tim Blair's weblog mutter amongst themselves as they huddle together away from the bright summer sun.

One says, "He's right. Where the unclean rabble drinks all the wells are posioned.

Another mumbles, "The rabble have damp hearts and dirty delights."

Another, who wears a white hood, says, "Their filthy words choke me. And I have to hold my nose when they pass me by."

Another says, "The wind from Sydney will blow the filthy rabble on the Adelaide plain away. Lets all spit into the wind."

July 16, 2003

interesting photographs

This is a very interesting online photographic magazine. The latest issue of 28m has a series of photographs by different photographers. Each of the indvidual series are all worth exploring.

In reading them I can see that the world wide web has given photography a new lease of life. The internet means that it is no longer necessary to work away towards a gallery exhibition or a book. Though I spent a lot of time doing photgraphy in the early 1980s when I had a studio, the traditional trajectory of an artist career was what stopped me from taking photographs. I stopped for most of the time that I was teaching and writing philosophy in the academy.

I stopped for two reasons. I could never get the work together for an exhibition. Secondly, I had to earning a living and I did not want to do so by being a commercial photographer, or working in a factory as I and bought an inner city cottage. So I became an academic. The photography was reduced and eventually it stopped. What was the point of photography? I was on an academic track. So I gave up the studio, I stopped taking the black and white urbanscapes with the 5x7 view camera, and eventually put the old Lecia in a drawer.

I started up photography again when I wanted some pictures on the bare walls of the electronic inner city cottage and to replace all the rustic gum trees at the beach shack in Victor Harbor. I shifted over to colour and landscape and started exploring the SA region. But, as I found film all very expensive I didn't produce that much:----what I could do on my holidays or on the odd weekend when at Victor Harbour.

But I had done enough over the last couple of years for me start to think about working in 5x4 sheet film for the landscapes with my old Linhof. However, I had reached a bit of a dead end as what would I do with the photos. You can only enframe so many photos for the walls of the house.

When I looked at the work in 28mm and read about the photographers new possibilities opened up. I can see that it is now possible to regularly publish the images on a weblog with a scanner, or more ambitiously to use the scanner to build a virtual gallery attached to a weblog. No need for an exhibition in an art gallery or a book.

An excellent example of what can be done is provided by Kurt Easterwood's hmmn: musings from the far east(erwood). It provides a model of what junk for code can aspire to over time.

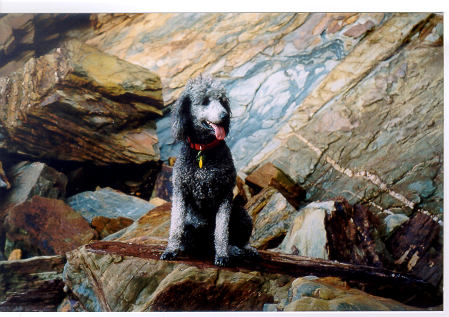

So I've decided to buy a flatbed scanner this week. In the short term I will scan snaps such as this:

This is Agtet, one of our two standard poodles. The location is between the towns of Woomera and Andamooka. It was taken with a Leica M4p on a trip in 2001. The image is called Xmas Greetings as I had used it for Xmas cards in 2001.

That particular desert trip included a weeks holiday in the opal mining town of Andamooka, which is just north east of Roxby Downs. It was there that I started taking landscape photos again. I eased my way back into photography after a decade with my old 6x6 twin lens Rolleiflex.

A scanner would give me reason to print more of photos that I taken since then 1991. Scanning them into the weblog and organizing them into some sort of gallery is much better than having the contact sheets and negatives sitting in a filing cabinet. That was the dead end I got into---it is what is happening at the moment. That had saddens me as I enjoy photography. But I felt trapped and frustrated.

Until I saw the 28m work online. But making the aspirations reality will take time as I do not have the technical knowledge to set up a galleryon the weblog. I'm a digital luddite.

Walter Benjamin: just a note

I briefly mentioned in passing on a previous post that Clement Greenberg's late modernist relationship between avant garde painting and photography as kitsch had been undermined by the mechanical reproduction of photography. I also briefly mentioned that an effect of photography had been to change our understanding of art.

What I had in mind was the work of Walter Benjamin and his argument that technological reproduction alters the way we look at reality. Benjamin argues that because of mechanical mass reproduction, art has lost its "authenticity" in the capitalist-oriented culture industry of the 20th century. This shift in attitudes to art from the hollowing out of art's traditional aura is the result of the introduction of mechanical means of reproduction.

Benjamin also emphasized the liberating, democratizing influences of the new techologies---still photography and film. The new mechanical means of reproduction of art undermined the foundations of traditional setup of one-off paintings produced by artists for their patrons in which the means of artistic production remain in the control of the rich and powerful. This was radically altered because mechanical reproduction meant that many more people could acquire the means to either take photographs of a work of art, or to be able to buy a cheap photograph, postcard, or print of the work.

This new media had the effect of fundamentally altering the relations between signifying systems in society as it eased the rigid divide between the art institution and the culture industry in which art protests the vulgarity of the market. The products of the culture industry could no longer be dismissed as kitsch, artistic trash and bad taste; or more politely, as the dross of art caused by art compromising itself with the market.

Another way looking at this transformation is in terms of the primacy of visual culture. This is best expressed by John Berger in his Ways of Seeing. Here he argues that our ways of seeing have a history:

"Today we see the art of the past as nobody saw it before. We actually perceive it in a different way."

In many ways what Benjamin was exploring, the historical transformation of art due to the mechanical reproduction of photographic images, is a history that we have been living through. This episode in the history of our visual culture has run its course, as we are now living through another one----the digital reproduction of images. In the digital era, with its computers, virtual reality, and the everyday circulation of images the digital form of image making takes on a life of its own.

In this world of the musem without walls there both an ongoing and infinite (re)production of images, and an endless change of these images. Not only is authenticity almost irrelevent the idea of authorship is almost obsolete.

July 15, 2003

its good to know where you stand

Here in little old Adelaide we have just had a popular festival of ideas around the themes of hope and fear. The smorsgboard of ideas was herald as a homegrown success due to the attendances being around 30,000.

It was not a success for the Anglo-Australian Sydney conservatives though. They sneered. Sydney may be looking rather tired, dirty and tacky these days, but its conservatives can still shrug their weariness off, free themselves from their disgust and raise a bit of their big contempt for the people.

I have previously mentioned the scorn of Tim Blair, who called the festival of ideas a carnival of the left-wing rabble. Now Gerard Henderson has also got in the contempt act about the people at the carnivalof ideas.

Henderson tells us that Adelaide is the place which laps up strident anti-Americanism; it is the home of a luvvies' collective where everyone (or almost everyone) agrees with everyone else; and it is besotted with cosmopolitan ideas of the future prospect of a world parliament.

Why it was a only yesterday that Adelaide was being denounced as the home of protectionism, populist resentment, anti-development, a lack of get up and go and suburban stupor. And South Australia is being mocked as a 'not-in-my-backyard' state because it resists being a repository for low level nuclear waste.

Poor Adelaide. It can never win a trick. But at least its not provincal anymore. The suburban masses have stirred, and they embraced cosmopolitianism.

July 14, 2003

Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others #6

Rick's sixth post on Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others is another juxtaposition of image and text. This time it links Jacque Callott's suite of eighteen etchings called The Miseries and Misfortunes of War. These depict French soldiers committing atrocities against civilians in the province of Lorraine. This suite of images is juxtaposed with Lorrain Adam's review of Sontag's text.

Adams points out that in Regarding the Pain of Others Sontag reverses her thesis in On Photography. This held that photographic overexposure to atrocity shrivels our sympathy and conscience as readers and interpreters. Her thesis held that a photograph of war horror at first makes war more "real"; but that after a surfeit of such images we grow emotionally numb. In the langauge of Adorno there was no truth in photographic works. By that is meant that they did not challenge the status quo and disclose human aspirations. They are not autonomous art.

It was a popular thesis, if I remember. I recall that I was not convinced by it when I read On Photography. At the time I was running a photographic studio, doing undergraduate studies in philosophy and visual arts, and struggling to understand Clement Greenberg's wriytings on modernism and the avant garde

That was about the time that photography was struggling to be accepted by the conservative high art institutions, and had gone very formalist to establish its modernist creditionals. I got enough from Greenberg to understand that photography had no hope of being a part of the painting avant garde, and so it was kitsch. I sort of understood that this devaluation of photography was part of the long tradition of painters (ie., those with imagination) and their apologists kicking photography because it was produced by a machine and chemicals. Some arts were more art than others and photography was, at best an instrument to document the activities of painters and performance artists. (The latter were the new avant garde).

So I more or less interpreted Sontag's text as part of the high art attack on photography as a popular art; as an anti-photographic text by an aesthete working in the literary institution. I was puzzled by the attack on the visualscape that was then forming around us, and I put it down to modernist distaste for the popular, mass produced art and kitsch. But I did not have the tools to engage with Sontag even though I suspected that photography was in the process of undermining the nature of art. There I left it.

So we come back to the present, where Lorrain Adams points that Sontag has reversed her earlier position and now treats photographic images with more respect. What is she saying according to Adams?

Adams says that Sontag acknowledges that photographs, like any other way of conveying meaning, can be put to many uses and that harrowing photographs do not inevitably lose their power to shock. As the Iraq war indicated, photographs can be taken as evidence to marshal opposition to and action against the atrocities they represented.

Sontag says that we accept these as evidence even though we know that many war photographers were embedded in the military machine during the Iraq war, and we understandd that war photography has had many intended and unintended distortions over the course of its history.

Sontag says, Jacques Callot's 1633 etchings "The Miseries and Misfortunes of War," which represent atrocious suffering endured by a civilian population at the hands of a victorious army on the rampage" are different. These images are like Goya's The Disasters of War, a series of 83 etchings depicting Napoleon's soldiers' slaughter of civilians in Spain in 1808.They are a synthesis of what happened in the past not evidence. As they were made public long after the events they depicted, so they could not be taken as evidence to marshal opposition to and action against the atrocities they represented.

If we accept Malraux's museum without walls plus the network of images in cyberspace, then too much can be made of Sontag's photography (evidence) and painting (synthesis) distinction. Both photographs and etchings are images that interpret the suffering of war; and both require interpretation by readers to understand their meaning. If you like they are historical sources (traces of the past ) that we use with other texts to understand our own history. Photographs are more traces of the past than pristine fact; the traces becomes evidence when they are used in an argument to say that killing civilians is bad.

Sontag seems to imply that war photos as evidence can give us an objective account of the past; that these photos like facts in empricist history speak for themselves. They are unbiased and reveal the truth whereas art creates the truth. Sontag is not alone in this. Kurt over at hmmm: musings from the far east(erwood) mentions the primacy of the image over the text. In a post on moblogging he says that there is something:

"....that bothers me about this primacy of the image, and I think it relates to concepts of truth and authenticity that I like to question from time to time. There seems to be this idea, not just among mobloggers but among society in general, that if a thought or statement or report isn't accompanied by some visual representation, it is somehow less true or valid."

He then mentions, as an example, the photographs that circulated through the media vectors during the Iraq war.

"Take the embedded reporters in Iraq and the coverage from the major TV networks. More often than not, the images that were beamed back from Iraq to accompany the reporters' stories were artifacted, digitized, highly abstract visual accompaniments. They were, for all intents and purposes, worthless in terms of communicating information, of news, or even propaganda. Yet they were shown night after night. Why? Because they symbolized a kind of truth, a visual statement that said "we're in Iraq right now covering this war."

Image is king. There is something in that. I recall ressponding quite strrongly the photographs of suffering children and the video footage of riding with the tanks as they roared across the desert. There was an immediacy there that the words did not capture.

Yet, to be meaningful photos, like facts, needed to be embedded in interpretative discourses. We read both the image and the text; these readings, which are the work of readers/critics, place the image and text in a variety of other interpretations. These interpretations (pro-war anati-war etc) are then contestedas are the images. Criticism, (ie., the work of Sontag,) eases the passage between the image and the reader; it elaborates the images so that they may be more easily understood by readers.

Derek Allen Interview#5

The post picks up on the fifth part of Rick's interview with Derek Allen over at Artrift.In this part of the interview Rick picks up on an important idea in The Voices of Silence, the idea of the ‘Museum without Walls’. In the interview Derek makes three points.

1. Much of what we regard as art cannot physically be moved into museums even if we wanted to eg, the Sistine Chapel, aboriginal desert paintings or the rock paintings at Cave of Lascaux. It is not longer art as Greek and Roman art plus Western art since the Renaissance. It is now the art of all cultures and all times. So the ‘musée imaginaire’ is an imaginary one that contains all the works we regard as works of art no matter where they might be.

Thus is born the democratic museum or art gallery Malraux effectively liberates artworks from the stuffy setting of the established white-walled gallery that functions as a place of reverence.

2. Our ‘musée imaginaire’ is made up of those works that are important to us--- – works that we respond to, admire, and love. This implies that a colonial painting hanging a regional art museum does not necessarily mean it belongs in our ‘musée imaginaire’ – because we may be indifferent to it, as we often are. And secondly, your ‘musée imaginaire’ may differ somewhat from mine, or from someone else’s. This implies that we would now see the art in the art gallery for what it is --a particular cultural construction.

So many of us would include photographs, films, videos and CD-roms into our museums without walls. And we include digital works So a state-of-the art virtual Museum is a reworking of Malraux's musem without a walls. It has radical implications.

3. The phrase 'our museum without walls' does not collapse art into individual opinion or judgement. Derek says that Malraux holds that there are large areas of agreement about what we would all admit to our ‘museums without walls’.

The pathway opened up by Marlraux's museum without walls leads us out of the art institution into the broader visual culture way and so beyond what Adorno called the culturescape----ruins of historical buildings. It also historicizes Adorno's aesthetics with its focus on the social significance of great works of autonomous art standing in opposition to the culture industry and heteronomous art (eg., everything from religious icons to tribal masks, advertising and commercial cinema). Malraux's museum without walls highlights that the categories of aesthetics have been developed in terms of high art and are not that good or useful for analysing, interpreting and evaluating popular art works (eg., a film or cartoon).

Adorno regards autonomy as a precondition for truth in art and made truth the ultimate criterion for the social significance of any world of art. Adorno's reflections on art are pre 'the musem without walls', as they privilege modernist avant garde artworks at the expense of other forms. After Malraux we see that Adorno's reflections on autonomous art works presuppose the art institution and the way that Adorno thinks within this institution. Malraux undermines Adorno's distinction between autonomous and heteronomous art by challenging the tight connection between autonomy, truth and social significance.

Heteronomous art (eg., the popular art of a cartoon in a newspaper) may be truthful and challenge the status quo, and it may be more socially significant than autonomous works. Autonomy need not be a precondition for truth in art.

Nor need truth be the sole critieria for the social significance of art. In Australia the popular series Sea Change on the ABC was socially significant due to the power of public image making. Dallas is even more so. This indicates that there are a variety of reasons for art's social significance.

What is problematic with Malraux's museum without walls is the loosening of aesthetic norms in artworksWe all have hour own. But why are we elevating one kind of art into our museum and not another. On what grounds? Malraux is not convincing at this point----he simply says that there are large areas of agreement about what we would all admit to our ‘museums without walls’. This implies some form of normative historical aesthetics but it is not clear what. Which bits of the culture industry? Which bits of indigenous art? Which bits of the built environment?

What are the standards and critieria being used to select the bits for our museum? Is it popularity? Commercial success? Cultural heritage?

July 13, 2003

making cities work

Adelaide is in the midst of a festival of ideas. Tim Blair, keeps his iconoclastic image intact by calling it Adelaide’s Carnival of Sour Left Wing Rabble. The carnival for lefties that is supported by the SA Government, has a diverse program, including an urban theme that links into the ongoing concerns of the thinkers of residence programme about making cities work.

Making cities work is topical issue in spite of Tim Blair's disdain and anti-intellectualism. Despite the big shift to innercity living, the global city of Sydney, for instance, does not work well. Many people are leaving it because of the expensive housing, the 3-4 hours daily travel time to work and a polluted urban environment.

Adelaide, as Charles Landry, a thinker in residence points out, is too spread out to work properly. Though bounded by sea on the west and hills on the north, it is unbounded north and south. So it becomes a suburban spread with all the smaller communities becoming a vast expanse of housing with the southern beaches merging into one.

Adelaide is half the area of London yet has a seventh of its population. As a city Adelaide lacks the vibrant hubs and nodes around train stations and shopping centres where people can interact because of the multiple use: civic, retail, offices, services, cultural, entertainment. Consequently, shopping centres such as Marion, are often a building mass in an ocean of car parks; whilst some trains stations are not even connected to the shopping centre. It lacks the hubs and nodes where people stop, linger, and lead a public life rather than retreat into white picket fence domesticity.

Tim Blair may pour scorn on planning and aesthetics but bad urban design affects our lives. Adelaide started of well with the great colonial grid and became a town of rectangles with parks.

Looking back to the 1950s from now, we can see that Adelaide's progress or development was badly designed. There was lack of imagination then--it was all about cars, factories and public housing. There was little sense of urban joy, poetics or commitment to place. Suburban modernity in the Playford era was the Lucky Country: buying a home, planting a lawn, establishing a garden and washing the car in the driveway. The house was functional but it stood for quality of life. Those living in a wholesome suburbia turned an empty shellor box into some sort of place-bound home that stood for a flight from the stench, disease and squalor of the inner city.

What is now acting to make cities not work well? All the talk is about efficiency and we do not connect cities to place.

Today, bad urban design continues, because architectual design is disconnected from sustainablity and there is a lack of eco-friendly urban development. The urban ecologist, Herbert Girardet, another of Adelaide's thinkers in residence, has pointed towards sustainable dwelling. He has rightfully argued for solar hot water systems and rain water tanks to be made compulsory on all new buildings.

However, the ideas being tossed around about making cities work better have yet to be connected with dwelling.Or the lack of dwelling as the dark side of modernity. The form of glass skyscrapers of Mies van der Rohe signifies the indifference to poetic dwelling.

What we do is seek the traditional beachside shack to regain dwelling in the sense of belonging and rootedness in an unstable and constantly changing society. This stands for tradition, security and harmony. It guarantees wholeness and meaningfulness in a homeless world.

Or we turn to place as eco-rural living ecotone, as exemplied in Living at the Edge with its deep concern about protecting wilderness of Tasmania's old growth forests in the Tarkine from logging. From this perspective dwelling and urban life are opposites.

This forgets that place is a basic concept of architecture.It refers to the relationship between the built form to the landscape.

July 10, 2003

living with dogs

For those who share their lives with dogs. I just love that sign. It is so different to the authoritarian signs on South Australian beaches that increasingly ban dogs from roaming free on beaches with their guardians. Even deserted beaches in mid winter.

The phenomenon of dog attacks is increasingly being used to ban dogs from public places. There are less and less places where dogs can run free in a city, such as Adelaide. They are less free than the violent, abusive homeless kids who roam the city streets destroying houses and cars. It is the dogs who are monsters not the kids.

The above link is via Joseph at reading and writing. He has a lovely post on having dogs around, being included in their animal lives and living with them like an animal in the world. He expresses a way of living with then in a shared world. I have yet to Santayana's Animal Faith and Spiritual Life. But here is a link to a book by a philosopher writing about living with dogs.

Here is a photo of Ari, our apricot standard poodle, taken at Secret Beach Mallacoota.

The photo was taken when we were on holidays in May of this year.

And this is Agtet, our grey standard poodle.

The place is Petrel Cove in Victor Harbor. The photo was taken just prior to going on holidays.

Ooops, Suzanne says that the photo was also taken at Secret Beach in Mallacoota. And she is right.

literary culture vs visual culture

I've never thought of it before. That a high romantic literary culture would have been opposed to the emergence of a visual culture that was informed by photography and its concern with the real. I had always thought of photography in terms of its relationship to painting and it developing into a visual culture (cinema, television, digital reproduction and manipulation) that became the modern mode of representation.

This book review (via wood s lot) suggests the need to consider photography in relation to ra romantic literary culture. I had completely forgotten Baudelaire's protestations that photography leaves no room for the imagination. The romantics we continually condemned the images that began to form the visualscape around them.

July 09, 2003

Regarding the Pain of Others#5

Rick's fifth entry on Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others is about our horror at human suffering. The image selected is Titian's painting, The Flaying of Marsyas.

A description of the painting is here. In the painting Marsyas is being skinned alive. The painting expresses horror in the form of is a myth. This is the sublime in Edmund Burke's sense. Burke associates the fear of death, dismemberment, terror, and darkness (e.g., a howling wilderness) with feelings of the sublime. This account transforms aesthetics and this powerful current leads to Adorno's shudder.

Sontag makes the following remark about the sublime as horror:

"An invented horror can be quite overwhelming....But there is shame as well as shock in looking at the close-up of a real horror. Perhaps the only people with the right to look at images of suffering of this extreme order are those who could do something to alleviate it; say, the surgeons at the military hospital where the photograph was taken; or those who could learn from it. The rest of us are voyeurs, whether or not we mean to be."

We do not need myth. We have plenty of examples of historical horror that readily come to mind. There are those of innocent people killed in war (from nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima) or of people being brutually tortured. We think of the Gulag of the former Soviet Union, the German Holocaust, the killing fields of Cambodia and Rawanda.

So there is a role for art to express the horror of the twentieth century. There is no doubt that instrumental economic reason needs to create spurious irrational enclaves (criticism, populism etc), and it treats art as one of them in its seemingly rational world. However, as noted in a previous post, the language of asethetics lends a voice to human suffering. If art's conception of truth is couched in the language of suffering, then it ought to speak about the big historical horrors. It is a form of knowledge.

Let me give an example from Australia in the form of the deep suffering of indigenous people, due to genocide. By this is meant the destruction of people by white Australia through systematic violence and systematic racial discrimination. That has yet to happen. Consequently, the white Australian nation is haunted by its history, and shamed by the revelations of the Bringing Them Home Inquiry. The ghosts of the past do inhabit the nation, and will do so until the unspeakable is expressed. Art can express the suffering contained in the words Genocide, Trauma, Guilt, Shame, Willful Forgetting, Denial

That is the historical example of horror that resonates with Australians. Each people would have their own historical horror.