April 30, 2009

digital photography

In Through a glass, darkly: photography and cultural memory Alan Trachtenberg raises the issue of the difference that digital photography makes. He quotes W.J Mitchell who points out in his book, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era, that calling these new instruments "electronic photography" or "digital camera," in hope of easing the passage into a new regime of picturing the putative "real world" we are using metaphors that misleads, and obscures the digital difference.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, fish, Kaikoura, New Zealand, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, fish, Kaikoura, New Zealand, 2009

Mitchell says that although a digital image may look just like a photograph when it is published in a newspaper, it actually differs as profoundly from a traditional photograph as does a photograph from a painting. Based on changes in chemical emulsions caused by exposure to light, old-style photographs are analog or continuous tone images; computer-generated images are digital, based on discrete units called pixels, entirely the product of computer programs.These programs may include actual photographs converted into digital images, which then can be altered, reprocessed, or recombined to produce an image as if made in the old manner of light-generated images.

As a result, Mitchell writes that we are faced:

with a new uncertainty about the status and interpretation of the visual signifier...The inventory of comfortably trustworthy photographs that has formed our understanding of the world for so long seems destined to be overwhelmed by a flood of digital images of much less certain status.

Trachtenberg adds that with electronic image-making having effectively taken over and computer memory established as the matrix of images-of-the-world, we are already well within the era of post-photography. Digital photography reinforces recent post-Enlightenment suspicion that "reality" is something made up, a construction, not something secure for a camera to confirm. More likely the camera is part of the game, not to be trusted as a guide to anything but itself. What is lost, on this argument, is a sense of the photograph as an actual portion of the visible world, a physical trace or residue of an actual event within light.

I'm not sure what to make of this argument. It strikes me as overdone. There is not that much difference between a photograph taken with a Leica and film and using the darkroom and a photography taken with a Leica and film and using Adobe Lightroom. We are mostly a talking about the difference between a negative and a digital file ---not the final image. It strikes me as nostalgia for old technology. Much ado about nothing.

April 29, 2009

red caravan

The caravans, like the boatsheds and the holiday batches, really stood out on the road trip on the west and east coast of the northern part of the South Island. Though the caravans were from an another era----the 1950s + 60s--- many, like this one at Rakautara on the Kaikoura Coast in the Marlborough district, were very well cared for.

They offer an insight into the funky culture of New Zealand---the sense of craft, the respect for historical objects, the capacity to live in the landscape rather than bulldoze the forest to build a house that dominates the landscape. An insight that suggests that the modernist bias against traditionalism and the avant garde's ideal of no place (utopia) did not sweep all before it.

Sure, the photo is an affirmation of New Zealand, rather than an expression of the underlying isolation, unease, alienation and anxiety that sits just below the surface. It is an image of how New Zealanders would like to see themselves--that they care for old things as well as the landscape. They were comfortable or at ease with their landscape, far more so than Australian's who are at odds with their land and desired to dominate and control it.

The postmodern turn to everyday life is also comfortable structure of feeling because New Zealanders never really left it to embrace a modernist utopia of a 'no place" based on the new industrial order that swept away the old. New Zealand , as 'their place', was already a paradise. There was no need to desire to go beyond the boundaries to the historical present, the everyday and the common language‘.

Modernism in New Zealand can be interpreted in terms of the contemporary the artist growing up in a provincial society and reacting against the culture of New Zealand as a late colonial settler society. The sense of artistic and intellectual isolation (in Wellington, Christchurch or Auckland) produced a modernist response in the 1940s and 1950s, which both exaggerated their apartness as an artist in an unsympathetic environment but also made it the basis of a artistic persona. It is a striving to sound and look sophisticated and cosmopolitan by removing all the indicators of a provincial or regional place.

This modernist narrative of becoming a modernist artist by staging a break from the smug provincial colonial culture of New Zealand (a culturally barren New Zealand) rests on a series of binaries — modernity versus tradition, province versus centre, national versus cosmopolitan, Victorian versus modernist. It is seeking an escape from the nightmares of colonial history into the autonomous realm of art.

Influenza A (H1N1)

A pandemic threatens. Everybody is wearing masks. The virus (Influenza A (H1N1) is present in Australia but we do not know yet how severe it will be. Still anxiety and fear skyrockets as as the death toll continues to rise.

Leunig

Leunig

The WHO has said that it was "very concerned" about the spread of the virus after it raised the pandemic level to phase four, which recognises that there is now sustained transmission of the infection from human to human. It is two phases short of a pandemic.

April 28, 2009

New Zealand Photography: Anne Shelton

New Zealand was the poster child of neoliberalism in the 1980s, under the Lang Labor Government, due to Roger Douglas, Labour's finance minister in the late 1980s, making it a small, open, flexible economy, emphasising negative freedoms, and shaping the shift to the politics of individualism and a minimalist conception of the state. New Zealand, under Helen Clarke then reversed direction at the beginning of the 21st century ('third way’ government?) and placed an emphasis on culture as a means of reasserting national identity.

In the process it became part of the globalised world, rather than standing outside marginalised and isolated, with photographers and artists exploring the paranoia, alienation, and unease sitting below the bi-cultural surface. This aspect of national life has seeped quietly into the music, literature and film-making as well as its visual arts practice. I'm not sure how this "seepage" relates to the modernist bias against traditionalism.

Anne Shelton, who had shifted from being a photojournalist to a photographic artist, is an example, as she photographed crime scenes that embodied deviant behaviour and female pathology.

Anne Shelton, Tracker, Hanging Rock, Australia, 2002, Diptych, C type prints, from the series Public Places

Anne Shelton, Tracker, Hanging Rock, Australia, 2002, Diptych, C type prints, from the series Public Places

Hanging Rock is a classic example of this in Australia and Shelton is another example of New Zealand photographers exploring Australia. Australian photographers are less likely to explore New Zealand.

The dark undercurrent of isolation and anxiety is the flipside of Christchurch’s genteel English appearance; a city that modestly prided itself on being ‘more English than England’. Its tabloid press thunders on and on about Maori crime and the need for much tougher law and order, whilst affirming customary values in the face of twenty first century violence.

Anne Shelton, Doublet, Parker/Hulme Crime Scene Port Hills, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2001

Anne Shelton, Doublet, Parker/Hulme Crime Scene Port Hills, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2001

Prejudice, violent abuse, and especially murder can be counterposed to the quaintly English façade of Christchurch. This undercuts the New Zealander's convention of using the otherness of the foreigner as a mirror, not so that they can discover how they are perceived but so that they can confirm their idealised image of themselves and their country. That idealised image has become a commodity for the international tourist market.

April 27, 2009

New Zealand Photography: Peter Peryer

Peter Peryer is an established contemporary New Zealand photographer, who has been working since the early 1970s and has recently published a monograph. His roots lie in Photo-Forum workshop with Peryer producing the dark, brooding images of that characterised his1975 Mars Hotel folio.

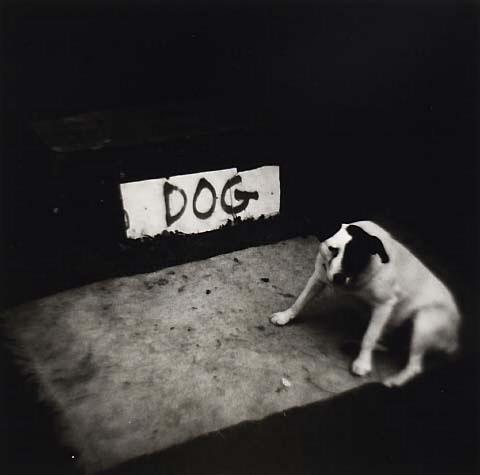

Peter Peryer, dog, 1976, silver gelatin print

Peter Peryer, dog, 1976, silver gelatin print

There is a simplicity to Peryer’s photographic approach, verging on the snapshot aesthetic, but the photographs express a sense of anxiety and dislocation and have been likened to film stills.

Second Nature was an exhibition that was published in1995.

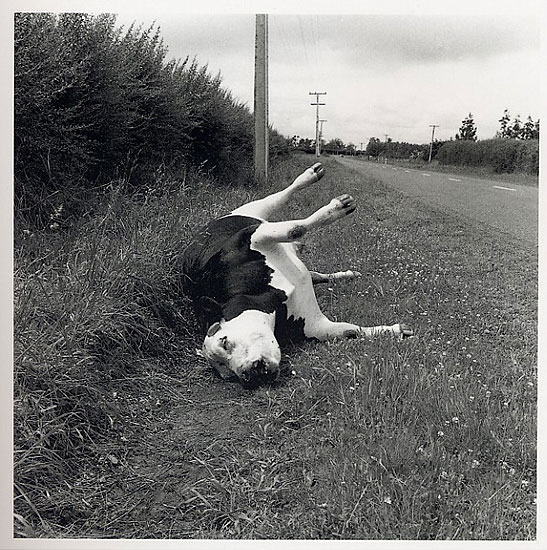

Peter Peryer, Dead Steer, 1987, silver gelatin print

Peter Peryer, Dead Steer, 1987, silver gelatin print

The advertising posters for the show, which were all around the city, featured the above photograph and expressed a sense of surreal estrangement. There was a tendency for the latter work to become more abstract:

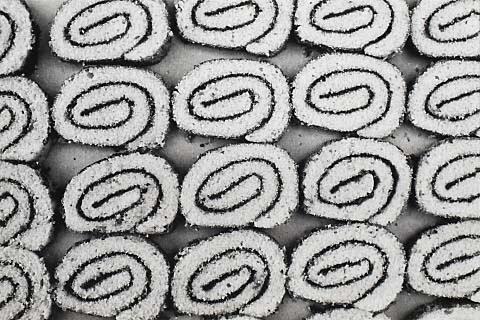

Peter Peryer, Swiss Roll, 1983, silver gelatin print

Peter Peryer, Swiss Roll, 1983, silver gelatin print

Peter Peryer Photographer presents the last two decades of work and is the first major publication to include Peryer’s colour photographs, integrating them with his 1990s black and white images and includes the shift from analogue to digital photography.

James at Photography Matters draws attention to the simplicity of Peryer’s style of photography:

The sophistication of Peryer’s photography lies in its apparent simplicity—we know What we are being shown, but now, Why?—and this is one of the reasons his images stay with us, reside in our subconscious and resonate, while others’ photos are not so well retained.

April 26, 2009

Kaikoura coastline

In his recent The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure and Human Evolution book Denis Dutton, the editor of Philosophy and Literature and Arts and Letters Daily, argues that art is not only a cultural phenomenon, but a natural one as well.

Like language art is in our genes in the sense that the arts are grounded in “a universal human nature”, and that only an evolutionary account, a “Darwinian” aesthetics, can explain their origins, their features, and their significance. This is a universalist theory of art that is opposed to the view that art is socially constructed and culture specific. For Dutton this ideology means that everybody's living in his or her own socially constructed, hermetically sealed, special cultural world.

The general argument is that since habitat choice was a life-and-death matter for early hunter-gatherers, human beings became innately sensitive to certain qualities of habitable landscape. Those who lacked this sensitivity were less likely to survive long enough to reproduce and, even if they did, their offspring might not have fared well. Factors such as the presence of water, lush foliage (and perhaps even climbable trees) were not merely aesthetic choices.

Dutton’s thesis is that universal features of our appreciation of landscape—our landscape aesthetic—were formed in this evolutionary environment As he puts it, “we are what we are today because our primordial ancestors followed paths and riverbanks over the horizon.” And painters, he suggests, have devised ways of triggering the pleasurable responses that arise from such evolved adaptations.

Thus artistic activity is itself adaptive—an inherited feature that increases our chances of survival and reproduction — and not, as Stephen Jay Gould and Steven Pinker claim (although Pinker

makes an exception for fiction), a mere byproduct of adaptations important for other, independent reasons. Alexander Nehamas in The American Scholar describes Dutton's argument thus:

Dutton attributes, for example, three distinct adaptive advantages to fiction: it encourages counterfactual thinking, allowing us to react more flexibly to novel situations; it advances the exploration of different points of view, providing a better understanding of others and guidelines for social behavior; and it supplies factual information. A source of knowledge and a honing of the imagination and the emotions, fiction is a product of natural selection.

I find Dutton’s naturalism fair enough in that art does need to be connected with an evolved human nature This aspect of a “Darwinian” aesthetics is reasonable and acceptable, and it can be linked to Nietzsche's naturalist understanding of will to power.

What is problematic in The Art Instinct is the art-critical agenda which involves an attack on modernism, in which Dutton argues that modernism represents a wrong pathway (ugliness), and that Darwinian aesthetics can restore the vital place of beauty, skill, and pleasure as high artistic values. Idf modernism was the wrong path, then postmodernism represents a dead end.

Anzac Day: mythology

It is true, as The Age points out, that the resurgence of Anzac Day and its popularity among the young:

suggests a collective willingness to separate political ideas about the worthiness of the conflict from the respect shown to the men and women who served...As a nation, we appear to have learnt the bitter lesson of Vietnam: that a great deal of damage is done when we blame soldiers for obeying the orders of their government. It is also encouraging that although Anzac Day could well serve as a de facto national day, it has not become an occasion for bombastic military displays. The sacrifice of the soldiers is its focus and gives the day its emotional depth.

So Anzac Day can serve as an ethical touchstone to judge other aspects of our national life and the way we view others:

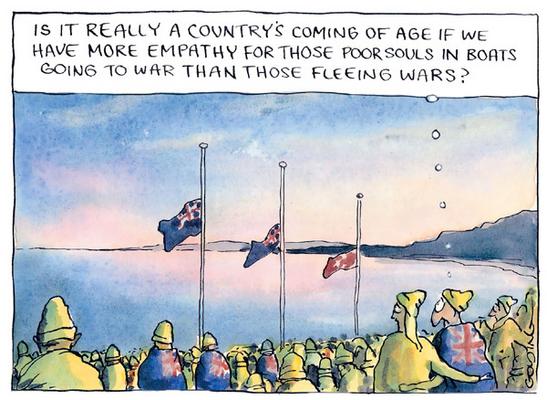

Matt Golding

Matt Golding

Though Anzac Day has not become an occasion for bombastic military displays there are grounds for reservation and concern. It is more than just publicly remembering the heroic side of Australia's experiences of war - our diggers' eagerness to enlist, their courage in battle, their mateship and their tragic but noble deaths.

As Marina Larsson observes in The Age:

The iconic Anzac is a youthful, able-bodied man with a magnificent physique - not a disabled "wreck''.In the Anzac legend, there is little room for the realities of war, of being blown to pieces, machine-gunned or bayoneted. Even today, official speakers seldom speak at length about soldiers who were "unsuccessfully killed'' and lived with the scars to prove it.

The Anzac myth is one in which we remember how the 60,000 "glorious dead'' supposedly gave birth to the nation, but we do we not similarly honour the 90,000 young men who were disabled giving birth to the nation.

April 24, 2009

rusty, decay

In the middle of the wilderness of Queen Charlotte Track stands the rusty symbol of the industrial /car civilization. Though the Track ran through private property at this point near Resolution Bay, that part of the Track was only accessible by boat. How come the van was there? There are no roads. Access is by boat? What use was a van in this neck of the woods? What value was it?

Gary Sauer-Thompson, rusty car, Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, rusty car, Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand, 2009

What we see here is nature slowly reclaiming the rusting industrial machine. It reminded me of what was happening in South Australia as the dairy farmers leave the land because of lack of water in the river. The land ever so slowly recovers as the plants return. The modernist domination of nature by turning the river into an irrigation system had failed.

April 23, 2009

photography, history

Photography was the defining modern mode of representation in the early twentieth century, in that there can be no thinking of history that is not at the same time a thinking of photography. Just think of photography's dual position of privilege in both the bureaucratic archives of the police, government, etc. and the family photograph album; or the preoccupations with the connections between photography, history and memory and the relation between image and text as contested ground. Or the conception of history as the mythic dimension of "collective fictions" that demand excavation for their underlying "truths.

Walter Benjamain's The Arcades Project, a mosaic of fragments, quotations and commentaries, offers a history of capitalism, with an emphasis on the transformation from a culture of production to one of consumption. Vanessa R Schwartz in Walter Benjamin for Historians says:

According to Benjamin, capitalism endowed objects with the means to express collective dreams. This drew him to particular urban architectural forms such as arcades, railway stations, department stores, and wax museums, which he called "dream houses of the collective." Such spaces seemed to acknowledge at the very least, perhaps even call into being, the crowd that would play such a vital role in both modern political revolution and the revolution in consumer culture. "In these constructions, the appearance of great masses on the stage of history was already foreseen." In these structures, the historian would discern the unfulfilled hopes and desires of the collective. For Benjamin, the nineteenth century resulted in a sleep induced by capitalism, which, by implication, had led to the rise of fascism: "Capitalism was a natural phenomenon with which a new dream-filled sleep came over Europe, and, through it, a reactivation of mythical forces." A work of history such as this was vital in order to slay capitalism by waking the slumbering collective from its nineteenth-century dream, because, as he wrote, "capitalism will not die a natural death."

The task of the historian thus became to use history as a "technique of awakening," and this project, he wrote, "deals with awakening from the nineteenth century." Benjamin's project of awakening involved the "unconscious world of remembrance" in the form of dream experience.

History is like Janus: it has two faces" pointing in two directions at once and expressive of both oppression and liberation.

April 22, 2009

memories of....

My trip through the northern part of the South Island was enframed by my children memories of visiting these places during my summer holidays. I kept on getting flashbacks that had little accord with reality. This image of Queen Charlotte Sound was my only attempt to represent my memory using the camera.

It probably worked because Queen Charlotte Sound still looked the same from a boat as a couple of decades ago.

It raises questions about the image, or rather what we mean by what we mean by “image”. W.J.T. Mitchell remarks, when we speak of images, we might well, “speak of pictures, statues, optical illusions, maps, diagrams, hallucinations, spectacles, projections, poems, patterns, memories, and even ideas.” He suggests we think of images as, “a far-flung family,” encompassing the mental, optical, graphic, sculptural, architectural, verbal, and perceptual

The underlying meaning or concept of the “image” that we usually employ when talking about pictures relates to a notion of the image as “likeness,” or “resemblance”—the image-type that Mitchell places at the very root of his family tree. The idea of the image as “likeness” need not suggest some crude form of mimesis, of reflecting or mimicking or mirroring an external reality since interpretation and memory is involved.

April 21, 2009

The Band: Opheleia

The song is Ophelia from The Bands comeback and swan song album Northern Lights Southern Cross. It was 1975 and it was their first album of all new original material in four years. The group had re-located to California from Woodstock and Robbie Robertson wrote all the material.

The Band's new sound is the result of a revolution in instrumental and recording technology and not of a revolution in ideas."Ophelia" is of interest principally because Garth Hudson has overdubbed an orchestra of brass woodwinds and synthesizers, and dovetailed all his instruments precisely into the deliberate pulsation of the tune's rhythm track.

In retrospect Northern Lights-Southern Cross with its themes of loss, displacement, and history sounds like a summation of their musical career It's almost a country album, heavily-influenced by folk, but the New Orleans horns return for "Ophelia," and the bluegrass opens up on "Acadian Driftwood," a rolling and affecting number.

photography, place, visual culture

A deep seated assumption in our culture is that literature can somehow be taken to “stand for” culture at large. This assumption holds that it is literature or, more specifically a literary culture, that should be given pride of place.

Moreover, it is an axiom of recent poststructuralist theory that language is a privileged category, our key means not just of communicating, but of knowing, of being human, of constructing and manipulating social reality. Australianness or Kiwi is therefore equated with language or the novel.

True, landscape painting--eg., the Heidelberg School in Australia --- is held to embody nationality, and this contests the privileging of language and a literary culture. When it comes to sense of place it is possible that seeing precedes saying. If this is the case, then it is also possible that when we are talking about the underpinnings to collective or national identity, it is visual representation, not writing, that provides our privileged entry.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, Golden Bay, South Island, New Zealand, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, Golden Bay, South Island, New Zealand, 2009

Photography, however, has not been considered to be an integral part of a sense of place, collective identity, or sense of being-in-the-world. If we adopt the perspective that visual representations or visual culture possibly provides a better or alternative representation of a national being in the world than language, then photography has, so to speak, lived in the shadows, largely forgotten, even tough thousands of photographs have been taken since the late nineteenth century. Film has replaced landscape painting.

Yet we look at our history of a particular place through archived, largely black and white photographs since memory is not a reliable guide of what once was. What we are left with are the pictures – simple, graphic, unmediated representations of self-in-place which express what is surely the most basic human mode of existence “here I am here in this particular built environment”. The photogrpahy goves us an indication of the built environment as it then was, and the clothes that indicate the gender and class of the 'I".

April 20, 2009

New Zealand Photography: Theo Schoon

In continuing my digging around around the history of New Zealand photography I have shifted my focus back to the 1950s and 1960s when modernism ruled in the art institution. What kind of modernism was being produced in New Zealand. Was there one that embraced vitalism (flow or becoming) as opposed to a machine aesthetic that celebrated the machine and industrial civilization as the new utopia? Was there a regional modernism that tried to construct a visual language to express their experiences of local cultural space; one that rejected the prevalent use of landscape painting to depict the national identities of New Zealand?

I stumbled upon Theo Schoon, who trained at the Rotterdam Art Academy from 1931-35. Arriving in New Zealand in 1939, Schoon briefly attended the Canterbury University College School of Art before moving to Wellington in 1941, where he met the artists Rita Angus and Gordon Walters who were impressed by his knowledge of painting, sculpture, photography and printmaking.

When he first moved to Rotorua in 1950 he began a photo-series that he called his 'thermals' (mudpools and other geothermic activity) a subject to which he would return over the next 25 years. What was produced was an impressive body of work yet Theo Schoon has been edited out of the history of New Zealand art.

Theo Schoon, mud 2, circa 1967 silver gelatin print

Theo Schoon, mud 2, circa 1967 silver gelatin print

Abstract and organic and movement (ripples and oozes). The image is a close-up, taken looking down, to produce a flattened out view. Though the camera is used as an exploratory device to produce an impressive body of work Theo Schoon has been edited out of the history of New Zealand art. That the thermal photographs have been ignored by the art establishment for so long is a reflection of the lowly status given to photography in New Zealand, until very recently.

Theo Schoon, mud pool 4, no date, silver gelatin print

Theo Schoon, mud pool 4, no date, silver gelatin print

These the photographs of the thermal areas near Rotorua result from years, from sun-up to sun-down, recording effects of light, colour and texture on mudpools and surrounding areas of thermal activity. This is the eye for the unexpected, a detail, a texture or a fleeting pattern caused by a mudpool bubble bursting, that Schoon represented with his lens.

He took these images with 21/4 square twin-lens reflex cameras - an Ikoftex and then a Yashicaflex. Many of his shots were taken with the camera hand-held, even in the case of exposures down to a thirtieth of a second or slower. Only after his return to Rotorua in the mid-60s did he move on to colour photography (ektachrome transparency). At that period he began to use a single lens reflex camera as well - an early model Canon that needed a close-up lens for the detailed shots he often wanted.

Theor Schoon, mud pool 2, no date, silver gelatin print

Theor Schoon, mud pool 2, no date, silver gelatin print

For all his emphasis on broadening contemporary art in New Zealand in the 1950s and1960s---his intentions was to forge a new path for New Zealand art, one in which Maori and European art would be integrated to produce a local modernism---Schoon was no modernist purist, despite the emphasis on the focus on formal values (tone, pattern, texture and shape). He refused to separate ‘art’ and ‘craft’, and his major artistic interests were carving gourds and pounamu (greenstone), Māori and Indonesian art, designs for ceramics, and paintings, prints, and photographs.

April 19, 2009

Buller River #2

In Total Recall:Contested depictions of the Romantic Tradition in the first edition of Second Nature Professor Peter James Smith argues that the legacy of the sublime in German Romantic Painting is alive and well in the late postmodern period of our time, post-9/11. Smith's paper gives contemporary instances of the sublime.

My interpretation of the sublime from my recent trip in New Zealand:

Smith argues that the interpretation of the sublime in the Romantic Tradition has become a contested site of representation in contemporary art and design practice, and that the currency of the Romantic Tradition has substance beyond a shallow focus on nostalgia.

An example of nostagia is Peter Dombrovskis' Rock Island Bend, Franklin River, South West Tasmania. Smith says that this photographic image has escaped deconstruction and remained intact as an icon of the wilderness movement, and adds:

Perhaps it could be said that it is for this very reason that wilderness photography has never reached the top of the pantheon in contemporary art circles. From an art world vantage point, there is a perceived danger that the image could be interpreted as quaintly "nostalgic", and hence the impact bubble of the political clout is deflated. It is better for wilderness photography to be binned in an entirely separate category of image making—out there on its own, to be used for a specific political purpose. And this is precisely a place where the general public can see it, appreciate it, value it, and keep it. Dombrovskis' image now has an iconic status: it is still famous today, 25 years after it was taken and 25 years after it was in full sight of the public and media.

He says:

This questioning over how a contemporary artist might represent the world based on a real experience of it, has impacted on how I view other contemporary artists' representations of landscape and still life and, of course, how I configure my own representations both as a visual artist and practice-based researcher. The inclusion of design practice here is to acknowledge that sublime representations are used to sell cars, movies, tourist destinations and the environmental movement.

The sublime is everywhere these post-colonial days. Smith adds that:

The Post-Modernists would point to the deficits of Romantic painting as a mannered artificial construct, insisting that the manner of the artifice is readily seen through, and that the audience, while initially experiencing uplift at the sight of an image by Friedrich, later feels disappointment when the artificiality of the image becomes apparent. To the Post-Modernist, a painting of reality is simply text to be "read" and is therefore very different from reality itself. However, the practice of painting, of making visual images that represent our environment in a convincing way, seems to run counter to this Post-Modernist stance. This is especially so if a contemporary artist wishes to make a political lobby or conservation point about the environment.

Though reading an image as a text is problematic as it implies literary as opposed to image), it is odd to argue against the insight that a painting or a photo is very different from reality itself. Though a part of as an image visual cultural, it is a representation of reality.

Smith argues that the contemporary sublime is not a let-down, pause, interruption, nor interrogation of banality: it is still a territory of uplift that feeds the positive drivers of the human psyche.

Cohen Brothers: No country for old men

No Country For Old Men, the latest film by Joel and Ethan Coen, adapted from a novel by Cormac McCarthy, uses the cliché of Hollywood movies of ‘the hunter becoming the hunted’. It relies heavily on the original work of Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Cormac McCarthy and is a film where the bad guys don't quite get what's coming to them.

It's all at the American dream ---any penniless guy born in a broken-down shack can, through grit and hard work, one day become Bill Gates. It’s a free country! Opportunities unlimited! No Country for Old Men, tis splash of cold reality. It’s very simple. You play with a drug cartel by taking their money--- making off with two million dollars in drug money-- and they're going to blow your head blown off with a cattle gun. The blue-collar worker, who is up against the men with the big money, loses badly. There's dark blood spreading on the floor everywhere.

In Killing Joke: The Coen brothers’ twists and turns in the New Yorker David Denby observes:

The movie is essentially a game of hide-and-seek, set in brownish, stained motel rooms and other shabby American redoubts, but shot with a formal precision and an economy that make one think of masters like Hitchcock and Bresson....But, in the end, the movie’s despair is unearned—it’s far too dependent on an arbitrarily manipulated plot and some very old-fashioned junk mechanics. “No Country” is the Coens’ most accomplished achievement in craft, with many stunning sequences, but there are absences in it that hollow out the movie’s attempt at greatness.

April 17, 2009

NZ Photography: Wayne Barrar

Wayne Barrar was born in Christchurch in 1957. He completed a Bachelor of Science from the University of Canterbury in 1979 and a Post Graduate Diploma of Fine Arts at Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1996. He is now Director of Photography at Massey University.

Barrar's subject as a photographer is the New Zealand landscape. He is less interested in the glories of nature ( the ‘untouched nature’ that is touted in ads and slogans about New Zealand) and more a interested in the relationship between culture and nature, and in particular, the marks human beings make on the landscape. In this picture we have the way that the iconic landscape is presented for the tourist gaze.

Wayne Barrar, Beneath Bowen Falls To Mitre Peak, Fiordland, 2000, Silver gelatin print, selenium toned

Wayne Barrar, Beneath Bowen Falls To Mitre Peak, Fiordland, 2000, Silver gelatin print, selenium toned

In his Shifting Nature he photographs a landscape harnessed to serve human needs and demands. It is the altered landscape ad he is conscious of photography's implication as a colonizing agent in framing views that imply ownership and control.

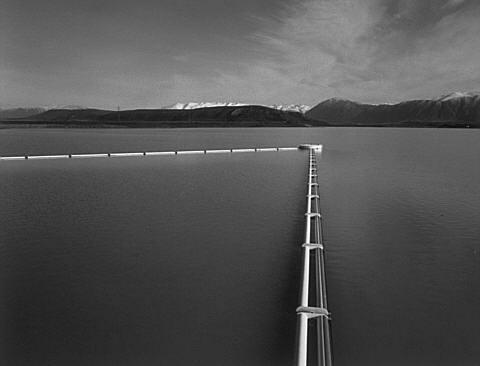

Wayne Barrar, barrier, Lake Ruataniwha, Canterbury, New Zealand,1987, gelatin silver toned print

Wayne Barrar, barrier, Lake Ruataniwha, Canterbury, New Zealand,1987, gelatin silver toned print

For instance, Barrar's photographs are in oppostion to the images produced for the tourist market, which romanticised Lake Manapouri as distant, splendid and untouched by development.

Wayne Barrar, Twin tunnels, Manapouri Underground Power Station, 2005, inkjet print

Wayne Barrar, Twin tunnels, Manapouri Underground Power Station, 2005, inkjet print

Barrar does not suggest any kind of achievement of industry over nature. He works in the American topographical tradition in the mid-1970s and their approaches to the man-altered landscape have remained a touchstone for Barrar.

Wayne Barrar, Room frontage (underground), Coober Pedy, Australia, 2003, Toned Silver Gelatin Print

Wayne Barrar, Room frontage (underground), Coober Pedy, Australia, 2003, Toned Silver Gelatin Print

opper Peddy is billed by its tourism promoters as Opal Capital of the World, and half of South Australia's Coober Pedy township of 3, 500 inhabitants live underground. It has been an opal mining town for nearly one hundred years. The first underground homes were built by World War I soldiers returning from the trenches in France.

April 16, 2009

in a warmed up world....

Westport on the West Coast of New Zealand was a regional town for a resource based economy---dairy farms, logging old growth native forests, and coal mining. Just like Tasmania it experienced the long battle between logging environmental protection from the 1970s onwards. By 2008 these had been resolved in favour of protecting the environment as wilderness and developing international eco-tourism to grow the economy. The tourist strategy, from what I could see, seemed to be working.

That leaves coal and, more problematically, the energy-based coal-fired power stations, in the warmed up world of climate change. The latter was effecting the West Coast landscape, which was drying out, especially in the northern part of Westland. Coal then became problematic.

April 15, 2009

critical encounters

The work of Mark Adams has given me a way to explore Australian history and memory in terms of the early European views of Terra Australis and the subsequent occupation of South Australia by British settlers and the dispossession of the indigenous people of their land.

My Rosetta Head project can be expanded from landscape to incorporate the history and cultural meaning of the landscape:--a rethinking of the history and narrative of colonial settler capitalism.

The beginning is imperial views from the perspective of the British from the boat looking at the coastline of Australia from the perspective of a voyage of discovery prior to the settlers:

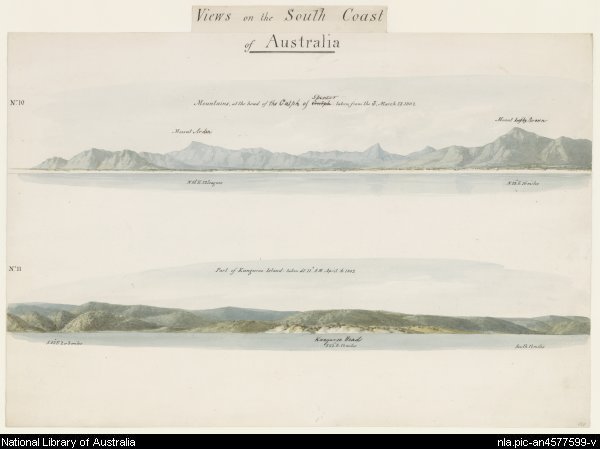

William Westall, two coastal profiles of southern Australian coastline

William Westall, two coastal profiles of southern Australian coastline

Kangaroo Island features more prominently in Westall's work and the perspective is one of discovery not conquest at the beginning of the country's European history. The conquest came latter with the settlers.

The imperial views from the perspective of the French on Baudin's boat looking at the coastline:

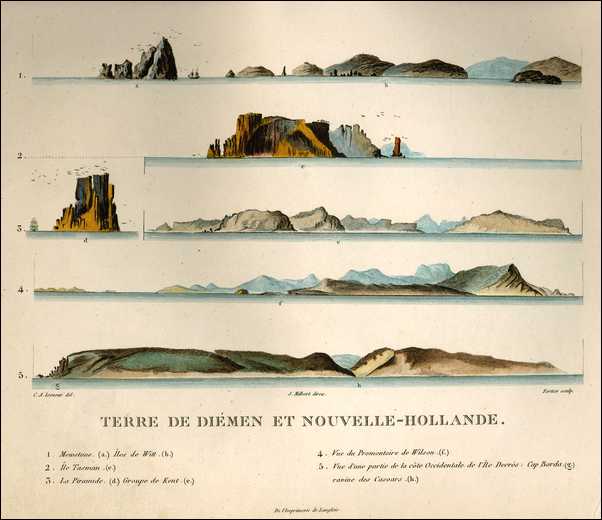

Charles Alexandre Leseur, coastal profiles, Plate III. Line 5 of this plate is a view of the west coast of Kangaroo Island, Cape Borda and ravine des Casoarss. From: Atlas historique : du Voyage de decouvertes aux terres australes, by Charles Alexandre Leseur and Nicolas-Martin Petit.

Charles Alexandre Leseur, coastal profiles, Plate III. Line 5 of this plate is a view of the west coast of Kangaroo Island, Cape Borda and ravine des Casoarss. From: Atlas historique : du Voyage de decouvertes aux terres australes, by Charles Alexandre Leseur and Nicolas-Martin Petit.

I don't know of any visual representation of the counter between Flinders and Baudin at Encounter Bay, Victor Harbor.

The subsequent occupation of South Australia by British settlers, and the dispossession of the indigenous people (tribes of the Adelaide plains, Mt Barker, Murray, Encounter Bay) of their land, initially took the form of whaling in Encounter Bay then settlement.

tourism

Fiji highlights the dangers of international tourism. It makes New Zealand so safe. No danger of a military coup there. It is safe enough that women can travel on their own.

It was not just backpackers walking the various tracks, it was middle class women as well.

April 14, 2009

history and memory

When I was travelling in New Zealand I was inevitably engaged with my past and my cultural memory of the official history of the nation, my historical sense of growing up and working in NZ in a resource-based economy, and my personal memory of the undercurrent of morbidity and angst in an insular and authoritarian colonial informed culture.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, cabin, caravan park, Karamea, Westland, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, cabin, caravan park, Karamea, Westland, 2009

I realized that New Zealand, like Australia, had been undergoing an upsurge in memory due to a questioning of its colonial heritage as a settler society taking place. If history it had once been the case that history was the sphere of the collective and memory that of the individual, then the shift was that the emergence of the idea that memory can be collective, emancipatory and sacred turns the old meaning of the term 'memory' inside out.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, mural, Greymouth, New Zealand, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, mural, Greymouth, New Zealand, 2009

What has emerged since the 1970s are those forms of memory bound up with minority groups for whom rehabilitating their past is part and parcel of reaffirming their identity.

Pierre Nora in Reasons for the current upsurge in memory in Eurozine says that this change has taken a variety of forms: criticism of official versions of history and recovery of areas of history previously repressed; demands for signs of a past that had been confiscated or suppressed; growing interest in "roots" and genealogical research; all kinds of commemorative events and new museums; renewed sensitivity to the holding and opening of archives for public consultation; and growing attachment to what in the English-speaking world is called "heritage" .

However they are combined, these trends together make up a kind of tidal wave of memorial concerns that has broken over the world, everywhere establishing close ties between respect for the past - whether real or imaginary - and the sense of belonging, collective consciousness and individual self-awareness, memory and identity.

Nora says that we are no longer on very good terms with the past. We recover it by reconstructing it in detail with the aid of documents, photographs and archives; in other words, what we today call "memory" - a form of memory that is itself a reconstruction - is simply what was called "history" in the past.

April 13, 2009

New Zealand Photography: Lawrence Aberhart

The last few years have seen a proliferation of survey shows and publications of New Zealand photography and photographers – for example, Marti Friedlander, Anne Noble, Peter Black, Ans Westra, Gary Blackman, and Wayne Barrar. Most of these photographers began their photography as part of the documentary tradition: the photo-journalist, the street photographer--- Magnum and Robert Frank etc.

Barrar is the exception, and while he is a documentary photographer, his touchstones are more those of the early 1970s New Topographic school – Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Frank Gohlke – and their offspring. Incidentally, Barrar is the only one not to have a survey show to coincide with the release of his book.

Another exception is Lawrence Aberhart, as he uses an 8x10” field camera, shooting almost exclusively in black and white, works in terms of long exposures and he photographs architecture, interiors and exteriors, cemeteries, monuments, and seascapes. His work is influenced by an earlier age of photography, by those who used the large format camera (such as William Henry Jackson, Carleton Watkins, Eugene Atget and Walker Evans), and it can be seen as interpreting the vernacular architecture of rural New Zealand.

Lawrence Aberhart, church, Oromahoe, Northland, 2002, silver gelatin print

Lawrence Aberhart, church, Oromahoe, Northland, 2002, silver gelatin print

I have selected Aberhart as part of my Christchurch photographers series. Aberhart lived in Lyttelton ---the port of Christchurch---in the late 1960s and he has been methodically and single-mindedly photographing New Zealand. Aberhart's first substantial body of work was a series of 8x10 inch contact print photographs taken in 1981/82 when he travelled by car throughout New Zealand and photographed buildings, monuments, churches, statues, memorials and marae. There is a melancholy about these works---the flotsam and jetsam of New Zealand's colonial legacy.

Many were, Aberhart considered, 'under threat' and he consciously undertook this series of documentation surmising that some objects would not be in existence or in a similar physical condition ten years later. Indeed, many of the photographed objects from this period now no longer exist. He describes himself as 'an eclectic collector of cultural debris, as it washes up, and before it disappears'.

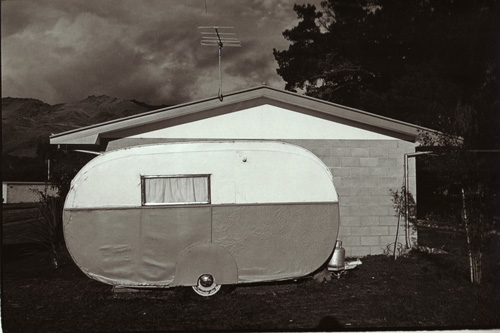

Lawrence Aberhart, caravan, Cromwell, 1977

Lawrence Aberhart, caravan, Cromwell, 1977

He consciously documents –in thematic series– sites of historical and/or cultural interest which are on the verge of disappearing and which he encounters on his trips. The bi-cultural character of New Zealand’s history provides a rich source for his images.

Lawrence Aberhart, Balclutha, silver gelatin print

Lawrence Aberhart, Balclutha, silver gelatin print

Aberhart's work is prominent in New Zealand and he is often seen as one of the forefathers of New Zealand's contemporary photographic history. His images are steeped in the history not only of his subjects but also of his chosen medium and his work constitutes a vital ingredient in the visual arts culture of New Zealand.

April 12, 2009

New Zealand photography: Mark Adams

Photoforum, which emerged out of the photographic new wave in New Zealand, is an Auckland-based:

non-profit society dedicated to the promotion of photography as a means of communication and expression.[It's] website showcases New Zealand photographic work and work of overseas photographers with some connection to New Zealand or PhotoForum.

There is a lot on material online to explore. It has online exhibitions, the most recent of which is Photoforum 33. More significantly there is a collection of portfolios of New Zealand established photographers and a portfolio of member's work.

It also functions as a resource base for New Zealand photography as it shows the work of 161 New Zealand photographers. There is members only magazine called Memento--and a blog that keeps members up to date with news about photography.

Given all this it is rather surprising that there is little work or reference to Mark Adams, who works in black and white with a 4x5 Linhof view camera in interesting ways:

Mark Adams, Pioptiohai-Milford Sound, Atawhenua - Fiordland 1992, gelatin silver photograph, from Land of Memories: Scarred by People.

Mark Adams, Pioptiohai-Milford Sound, Atawhenua - Fiordland 1992, gelatin silver photograph, from Land of Memories: Scarred by People.

This body of work, which was done between 1988 and 1992, explored the South Island, tracing evidence of the Ngai Tahu people.

Mark Adam's latter work is Cook's Sites: Revisiting History which is a collaboration between Mark Adams and Anthropologist Nicholas Thomas on the early cultural contacts between Maori and European their journey to the sites from Cook's journeys and to the archives and relics collected by museums in Germany.

The sites of contact between Cook's crews and the Maori people who occupied the land are in Dusky Sound and Queen Charlotte Sound. The photographs and text examine the traces of the past in these places, opening up ambiguities, and critically evaluating the colonizing of the landscape sites:

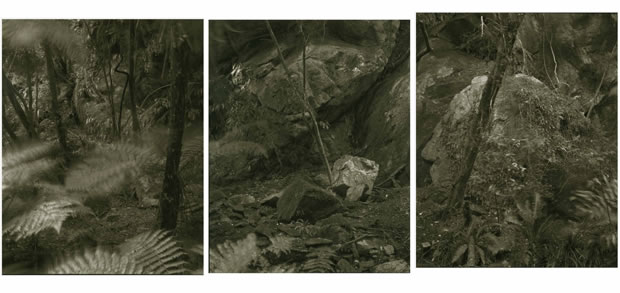

Mark Adams, Cook's Sites Cascade Cove, Tauwhare, rock shelter and midden, Dusky Sound, 1995, Gold toned silver bromide fibre-based prints 3 prints: each 600 x 510 mm

Mark Adams, Cook's Sites Cascade Cove, Tauwhare, rock shelter and midden, Dusky Sound, 1995, Gold toned silver bromide fibre-based prints 3 prints: each 600 x 510 mm

Some of the views recreate the scenes depicted by the artists on Cook’s ships such as the William Hodges painting of the waterfall in Dusky Sound in 1775 and John Webber’s depiction of the beach at Ship Cove at Queen Charlotte Sound in 1788.

David Bowie - Warszawa

"Warszawa"---homage to the capital of Poland and its people---is a mostly instrumental song by David Bowie, co-written with Brian Eno and originally released in 1977 on the album Low--the first album of the Berlin trilogy.

The Berlin years were ones where Bowie dried out (although relapses with hard drugs would continue for another decade), it taking two years for him to stop having flashbacks. He tried to regain some semblance of normalcy in his life in a poverty-stricken Berlin reverting back to its morbid decadence of the thirties.

There is a deep melancholy underpinning "Warszawa" and the four instrumental tracks on side two; they deal thematically with life in a Germany scarred with the Berlin Wall, but also with the ridding of Bowie’s LA demons.

I need to find an image for the music.

April 11, 2009

NZ Photography: Murray Hedwig

Christchurch, New Zealand, is my hometown, in the sense of my origins: I was born and educated there. I had to leave because I could not obtain work. I now revisit Christchurch to as a tourist on short visits (and see my mother) when I am on my way to somewhere else in the South Island.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, Christchurch chic, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, Christchurch chic, 2009

I thought that I would explore what I could find online about photography in Christchurch. There is Christchurch Flickr group. Digging around I come to realize that there is a history to contemporary photography in Christchurch. A dominant figure in this regional history is Murray Hedwig:

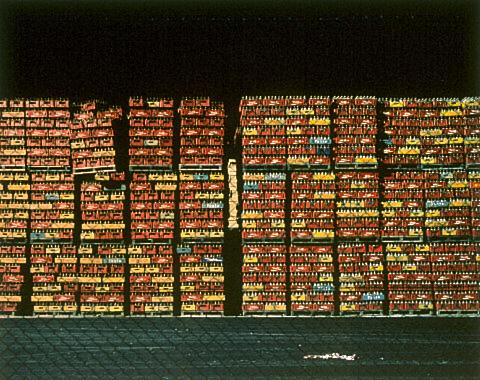

Murray Hedwig, Coca Cola Crates, 1976, Cibachrome Print

Murray Hedwig, Coca Cola Crates, 1976, Cibachrome Print

The shut-down narrow cultural world of 1950-1960s Christchurch is the background to Hedwig's education at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Canterbury. This did not have a photography department and so aspiring photographers studied graphic design and taught themselves photography.

Around 2005 Hedwig published his photographic essay of Australasian urban spaces entitled--- Public Spaces, Personal Views.

Hardwig says that the medium of photography is so accessible to everyone that if somebody is making images about the banal and commonplace in our environment, then I hope viewers ask themselves: “ Why has he photographed this?”

Murray Hedwig, Garage Doors (Red), 1980, colour photograph

Murray Hedwig, Garage Doors (Red), 1980, colour photograph

This latter more abstract work is quite different from the work exhibited on the Photo forum site especially Coca Cola and the suburban wires and houses. The latter are more a reworking the alterrd landscape style of the American New Topographics movement of the 1970s.

April 10, 2009

New Zealand Photography: Robin Morrison

Over at alfotonet.org on Flickr s2art comments on contemporary photography. He says that:

in this day and age of highly wired communities, [it is] nothing more than a hunter gatherer pursuit. An excuse to wander and look, to pause "briefly" and reflect, and for some wonder, at the world presented back to them. but then; what to do with all those images?

Reading David Eggleton's Into the Light: A History of New Zealand Photography provides an answer to s2art's question. The text indicates that it was common practice for New Zealand photographers in the 1980s to publish their work as photobooks.

Robin Morrison is one example. My eye was caught by his The South Island of New Zealand From the Road (1981); caught because I had been making the same kind of journey on a much smaller scale.

Robin Morrison, Caravan, Seddonville, West Coast, New Zealand, 1979

Robin Morrison, Caravan, Seddonville, West Coast, New Zealand, 1979

This kind of work is a break from the coffee-table books that flood the market with their pumped up colours, shop worn imagery, and the kitsch subjects of Pictorialist Romanticism.

Robin Morrison, Cabin at Pakawai camping ground, Golden Bay. 1979

Robin Morrison, Cabin at Pakawai camping ground, Golden Bay. 1979

Rhonda Bosworth says in Art New Zealand that Morrison's work is:

based firmly in a documentary tradition. He is essentially, to use John Szarkowski's definition, a 'window' rather than a 'mirror' photographer. That is to say, he explores and interprets the world in photographs specific to time and place rather than using the medium as an inward-looking means of self-expression.

From the Road abounds with photographs of people, unusual gospel halls, post offices and pubs, odd examples of deco architecture. Morrison is seen as the chronicler of that half-mythic landscape – the flatlands and caravans, the baches and pubs, the vast skies and the remoteness.

April 9, 2009

NZ realism/regionalism

Whilst in Christchurch I visited the Art Gallery to see some of the works that constitute New Zealand Regionalism, which focused on depicting the landscape of Canterbury and Otago in a realist manner. Typically the Regionalists (eg., Rita Angus, and Rata Lovell-Smith) were pre-modernist and opposed to the modernist shift to European abstraction and to American abstract expressionism.

The regionalists depicted the landscape without people, using buildings as the stand-in for the signs of human inhabitation. An example is WA Sutton, a Christchurch-based painter who taught at the very conservative University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts. This art school in the 1950s was resolutely committed to representational painting and encouraged accurate drawing rather than experimentation.

The Canterbury regionalists rejected the romantic traditions of scenic grandeur (including the sublime) and they developed a distinctive imagery focused on marks of settlement and physical features that typified the region.

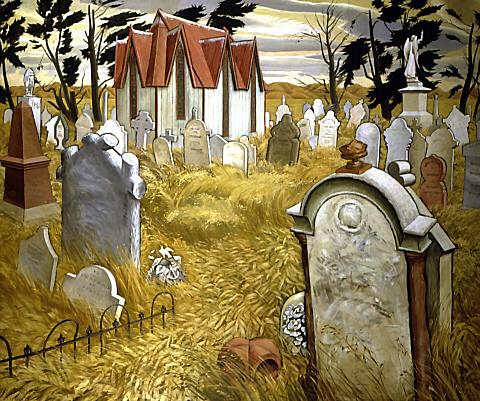

WA Sutton, Nor'wester in the Cemetery, oil on canvas, 1950

WA Sutton, Nor'wester in the Cemetery, oil on canvas, 1950

This is seen as an iconic painting of the Canterbury regionalists. Another iconic image is Cass by Rita Angas. These Canterbury School of artists worked with a simplified forms and objects in their compositions, and they were pre-occupied with the clear crisp light 'that transgressed the tradition of the British landscapists.

Rata Lovell-Smith, Hawkins, oil on canvas, 1933

Rata Lovell-Smith, Hawkins, oil on canvas, 1933

Rata's representation of the Canterbury landscape in paintings such as 'Hawkins' (1933) and 'Bridge, Mt Cook Road' (1934) influenced later artists, including Rita Angus and William Sutton.This regionalism showed an interest in subjects that were characteristic of the localities with which the painters were most familiar. The Canterbury School as a regionalist movement which expressed a growing awareness of a local identity and harboured aspirations for a distinctive New Zealand art.

Today, is the regional difference that stands out in a globalised world and international tourism. My own interest as a photographer after modernism is more the architectural form within the regional landscape:

Gary Sauer-Thompson, mountain hut, Arthur's Pass, Canterbury, New Zealand, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, mountain hut, Arthur's Pass, Canterbury, New Zealand, 2009

Landscape photography fits easily into this kind of regional realism.

April 8, 2009

Punakaiki River, Paparoa National Park

We left Christchurch early this morning for Adelaide--leaving steady rain and green fields for the dusty, dry landscape of South Australia that has had no autumn rain, nor is it likely to have. Compared to the South Island of New Zealand, southern Australia is definitely a brown, parched land. Depressingly so.

Looking back on the trip around the South Island that included exploring the Heaphy Track, the Abel Tasman Coastal Track, and the Queen Charlotte Sound walk we agreed that our favourite place was the Paparoa National Park:

It was the place in the South Island we both wanted to return to stay and explore in more depth in terms of walking and photography. It is a small national park with dense native forest, yet it's ecosystems are incredibly rich and diverse.

Limestone underlies most of the park and it is responsible for the area's landforms - high coastal cliffs, impressive river canyons, delicate cave formations and the bizarre ‘pancake-stack’ coastal formations that the area is well known for. This is a wilderness with virtually undisturbed forest cover that includes tree ferns and palms and it is mostly easy walking on very accessible tracks.

April 4, 2009

Pancake Rocks, Paparoa National Park

As mentioned in an earlier post we spent some time at the Paparoa National Park in the West Coast of NZ. My starting point was Punakaiki, known by tourists for its Pancake Rocks, which is as far as I got last year before returning to Christchurch.

This trip I gave myself more time by staying near the park so that I could explore the national park by exploring some of the walks along the rivers that had been recently constructed by the Department of Conservation. I was checking out the walks to see whether it would be possible to work in the park with a Rollei SL66 on a tripod. What was available behind the coastal strip and how accessible was it?

Craig Potton had explored the park when working as a ranger there, and he published this work as Images from a Limestone Landscape around 1987. How easy would it be for me was the motivation.

Some spots were very accessible--eg., the Truman Track and five minutes to a wonderful place to photograph--sandstone cliffs on the beach. If you go at low tide and head around the rock to the north there's some excellent rock formations.

April 3, 2009

international politics

I'm too far from newspapers and television to make any sense of what is happening. The G20 makes no impression in the wilderness. So I will rely on the cartoonists:

Moreland

Moreland

How this will affect us I have no idea. From what I can figure out the NZ economy is now very dependent on international tourism and tourism, in turn, depends on cheap airfares. So will the airlines continue to offer cheap airfares? I have no idea. All I see is that there are heaps of tourists in NZ and they are interested in the wilderness that NZ has to offer.

April 2, 2009

rock, Castle Hill

This is part of the landscape on the Castle Hill Station in Canterbury in the South Island. It is just prior to Arthur's Pass when approaching the pass from the regional city of Christchurch.

The landscape is a massive amount of bare limestone rock in a valley in the high country and a site for tourists on the way to the West Coast. More of my work is here You can see more images of the region in the work of John O'Malley, a regional photographer who lives in Christchurch. (I don't know if he is on Flickr).

Someone who is on Flickr is Kate Pedly a geologist. She was recently at Castle Hill and depicted the atmosphere of the basin.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, rocks, Castle Hill

Gary Sauer-Thompson, rocks, Castle Hill

On this occasion was more attracted to the rock forms than the atmospherics of the base.