February 25, 2011

Middle East: new democratic possibilities

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri in Arabs are democracy's new pioneers in The Guardian say that the revolts in Tunisa, Egypt and Libya:

have immediately performed a kind of ideological house-cleaning, sweeping away the racist conceptions of a clash of civilisations that consign Arab politics to the past. The multitudes in Tunis, Cairo and Benghazi shatter the political stereotypes that Arabs are constrained to the choice between secular dictatorships and fanatical theocracies, or that Muslims are somehow incapable of freedom and democracy....These Arab revolts ignited around the issue of unemployment, and at their centre have been highly educated youth with frustrated ambitions â a population that has much in common with protesting students in London and Rome. Although the primary demand throughout the Arab world focuses on the end to tyranny and authoritarian governments, behind this single cry stands a series of social demands about work and life not only to end dependency and poverty but to give power and autonomy to an intelligent, highly capable population.

The organisation of the revolts is based on a horizontal network that has no single, central leader. Traditional opposition bodies can participate in this network but cannot direct it:

the multitude is able to organise itself without a centre â that the imposition of a leader or being co-opted by a traditional organisation would undermine its power. The prevalence in the revolts of social network tools, such as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, are symptoms, not causes, of this organisational structure. These are the modes of expression of an intelligent population capable of using the instruments at hand to organise autonomously.

They say that the insurrections of Arab youth are certainly not aimed at a traditional liberal constitution that merely guarantees the division of powers and a regular electoral dynamic, but rather at a form of democracy adequate to the new forms of expression and needs of the multitude.

January 1, 2011

privatize, privatize, and privatize some more

In In Defense of the Public at In these Times Eve Ewing says:

In Another Kind of Public Education (Beacon Press, 2009), Patricia Hill Collins points out that Americans have come to associate anything âpublicâ with a notion of inferiority. âIdeas about the benefits of privatization encourage the American public to assume that anything public is of lesser quality,â she writes. âThe deteriorating schools, health care services, roads, bridges, and public transportation that result from the American publicâs unwillingness to fund public institutions speak to the erosion and accompanying devaluation of anything deemed public. In this context, public becomes reconfigured as anything of poor quality, marked by a lack of control and privacyâall characteristics associated with poverty.â

Ewing comments that the schema of capitalismâwhere the pursuit of private profits is sanctifiedâhas turned Americans shamefacedly away from the public life that is the birthright of all citizens in a democracy.

She adds:

The logic of this mode of thought has skewed roots in the principles of supply and demand, and it goes something like this: if something is scarce, it is desirable and valuable; conversely, if it is abundant and readily available it must be cheap or worthless. This calculus can reduce any and all things into commodities, the relative value of which can be determined by their level of unfettered availability to average people.

August 25, 2010

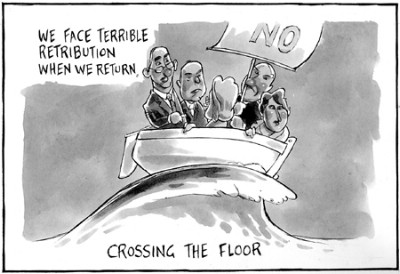

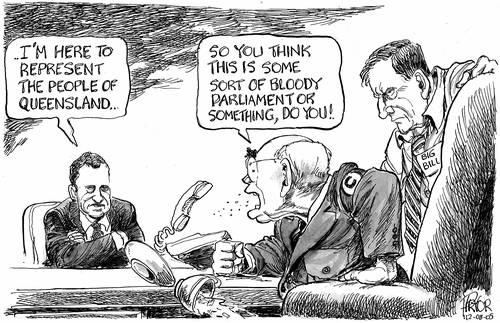

reforming parliament

Australia has a hung parliament with the balance of power being held by three regional independents as a result of a growing discontent with the Westminster system of two party system of liberal democracy and a desire for multilevel democracy. Australia is taking the first hesitant steps towards recognizing that the world as a whole is changing towards more complex and multi-party politics.

The reforms requested by the three regional independents are contained in this letter to the Prime Minister and leader of the Liberal Opposition. Though limited---they do not address the executive being in a powerful position relative to the legislature, nor proportional representation for the House of Representatives--they are significant and they may help to sway some more voters and politicians towards backing reform.

TO JULIA GILLARD and TONY ABBOTT

Requests for information

1. We seek access to information under the âcaretaker conventionsâ to economic advice from the Secretary of the Treasury Ken Henry and Secretary of Finance David Tune, including the costings and impacts of Government and Opposition election promises and policies on the budget.

2. We seek briefings from the following Secretaries of Departments:

1. Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy

2. Health and Ageing

3. Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

4. Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government

5. Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

6. Climate Change, Energy Efficiency and Water

7. Defence

8. Resources, Energy and Tourism

3. We seek briefings from caretaker Ministers and Shadow Ministers in the above portfolio areas to discuss their program for the next three years.

4. We seek advice as soon as possible on their plans to work with the Clerks of the Parliament to improve the status and authority of all 150 local MPâs within parliamentary procedures and structures. In particular, we seek advice on timelines and actions for increasing the authority of the Committee system, private members business and private members bills, matters of public importance, 90 second statements, adjournment debates, and question time.

5. We seek a commitment to explore all options from both sides in regard âconsensus optionsâ for the next three years, and a willingness to at least explore all options to reach a majority greater than 76 for the next three years. Included in these considerations is advice on how relationships between the House of Representatives and the Senate can be improved, and a proposed timetable for this to happen.

6. We seek a commitment in writing as soon as possible that if negotiations are to take place on how to form Government, that each of these leaders, their Coalition partners, and all their affiliated MPâs, will negotiate in good faith and with the national interest as the only interest. In this same letter of comfort, we seek a written commitment that whoever forms majority Government will commit to a full three year term, and for an explanation in writing in this same letter as to how this commitment to a full term will be fulfilled, either by enabling legislation or other means.

7. We seek advice as soon as possible on a timetable and reform plan for political donations, electoral funding, and truth in advertising reform, and a timetable for how this reform plan will be achieved in co-operation with the support of the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The three non-aligned MPâs will now be heading home to families, electorate duties, and a long-standing appointment with the Governor-General (unrelated to this political deadlock). We have agreed to be back in Canberra on Monday for the full week of meetings in relation to the above.

We expect all the above information to be made available through best endeavours as soon as possible, so that formal negotiations with all stakeholders can begin by Friday 3rd September â if, based on final counts, negotiations are indeed needed at all.

This letter is Julia Gillard's response. The Prime Minister says yes to the requests and is committed to parliamentary reform at the two levels, namely:

increasing the authority of the Committee system, private members business and private members bills, matters of public importance, 90 second statements, adjournment debates, and question time.

a reform plan for political donations, electoral funding, and truth in advertising reform, and a timetable for how this reform plan will be achieved in co-operation with the support of the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The Westminster system is designed to produce strong, single party government and the election results signify the death of two-party politics. In Australia it has taken this long simply because Labor and the Coalition had such an iron grip on power. The big issue is that despite the Greens winning 11.4 % of the vote, they only gain 1 seat? How is that democracy?

May 24, 2010

deliberative democracy + deliberation

The reigning paradigm in political science in the 1970s--1980s was a form of liberal democracy that assumed conflict among the citizens and prescribed handling those conflicts by apportioning power equally among the citizens in a vote or in the pluralist contest of interests. The emphasis was on bargaining and negotiation, to voting, and to the use of power.

It was then replaced by âdeliberative democracy,â that is based on dialogue, mutual justification and persuasion. In On Revolution Hannah Arendt describes the process as follows:

Opinions are formed in a process of open discussion and public debate.... The same is not true for questions of interest and welfare, which can be ascertained objectively, and where the need for action and decision arises out of the various conflicts among interest groups. Through pressure groups, lobbies and other devices, the voters can indeed influence the actions of their representatives with respect to interest, that is, they can force their representatives to execute their wishes at the expense of the wishes and interests of other groups of voters. In all these instances the voter acts out of concern with his private life and well-being, and the residue of power he still holds in his hands resembles rather the reckless coercion with which a blackmailer forces his victim into obedience than the power that arises out of joint action and joint deliberation

In On Revolution Hannah Arendt was trying to settle accounts with both the liberal-democratic and Marxist traditions; that is, with the two dominant traditions of modern political thought which, in one way or another, can be traced back to the Enlightenment.

Her basic thesis is that both liberal democrats and Marxists have misunderstood the drama of modern revolutions because they have not understood that what was actually revolutionary about these revolutions was their attempt to create a constitutio libertatis - a repeatedly frustrated attempt to establish a political space of public freedom in which people, as free and equal citizens, would take their common concerns into their own hands.

Both the liberals and the Marxists harbored a conception of the political according to which the final goal of politics was something beyond politics - whether this be the unconstrained pursuit of private happiness, the realization of social justice, or the free association of producers in a classless society.

Against liberals, Arendt disputes the claim that these revolutions were primarily concerned with the establishment of a limited government that would make space for individual liberty beyond the reach of the state. Against Marxist interpretations of the French Revolution, she disputes the claim that it was driven by the âsocial question,â a popular attempt to overcome poverty and exclusion by the many against the few who monopolized wealth in the ancien regime.

Rather, Arendt claims, what distinguishes these modern revolutions is that they exhibit (albeit fleetingly) the exercise of fundamental political capacities â that of individuals acting together, on the basis of their mutually agreed common purposes, in order to establish a tangible public space of freedom. It is in this instauration, the attempt to establish a public and institutional space of civic freedom and participation, that marks out these revolutionary moments as exemplars of politics qua action.

This understanding of deliberation was subsequently modified and expanded. Participants in deliberation advance âconsiderationsâ that others âcan acceptâ -- that are âcompellingâ and âpersuasiveâ to others and that âcan be justified to people who reasonably disagree with themâ . Disagreement, conflict, arguing, and the confrontation of reasons pro and con emerged more clearly at the core of deliberation.

This is a classic understanding of deliberation. It holds that democratic deliberation is necessarily interactive and collective; that deliberation in public has social features that tend to promote the common good; and deliberation allows creative solutions and the transformation of preferences.

July 19, 2009

Žižek on authoritarian capitalism

Slavoj Žižek in his article on authoritarian capitalism at the London Review of Books says that:

It is democracyâs authentic potential that is losing ground with the rise of authoritarian capitalism, whose tentacles are coming closer and closer to the West. The change always takes place in accordance with a countryâs values: Putinâs capitalism with âRussian valuesâ (the brutal display of power), Berlusconiâs capitalism with âItalian valuesâ (comical posturing). Both Putin and Berlusconi rule in democracies which are gradually being reduced to an empty shell, and, in spite of the rapidly worsening economic situation, they both enjoy popular support (more than two-thirds of the electorate).

The dignity of classical politics stems from its elevation above the play of particular interests in civil society: politics is âalienatedâ from civil society, it presents itself as the ideal sphere of the citoyen in contrast to the conflict of selfish interests that characterise the bourgeois.

Žižek says that Berlusconi is a significant figure, and Italy an experimental laboratory where our future is being worked out. If our political choice is between permissive-liberal technocratism and fundamentalist populism, Berlusconiâs great achievement has been to reconcile the two, to embody both at the same time.

July 7, 2009

people reloaded: why mass protest in Iran is true politics worth supporting

This is via infinite thought

This piece is copyright-free. Please distribute widely.

In the past two weeks, the majority of people in Tehran and other cities in Iran (including Shiraz, Ahwaz, Tabriz, Isfihan) have been on the streets, protesting against the theft of the presidential election by a handful of stateâs agents at the top level. It was not a rigging in the usual western sense, no added votes or replaced ballot boxes, the election went on properly, the votes were taken and probably even counted, the figures transmitted to the ministry of interior, and it was there that they were totally disregarded and replaced by totally fictitious figures. That is why all the opposition forces (Sazman-e-Mojahedin-e-Enghelab, Mosharekat party...) together with people called it a coup dâétat.

Global public opinion and, especially, the body of (leftist) intellectuals, Inspired by recent events in the middle Asia and east Europe, mostly regard this Iranian mass protest as another version of the well-known, newly invented, neo-liberal, U.S.-sponsored, colour-coded revolutions, as in Georgia and Ukraine. But is it the case in Iran? This article intends to clarify the issue, to reveal the properly political essence of current mass movement, and to demonstrate that this movement has the potentiality of a self-transcendence, of surpassing its actual demands, of traversing its current phantasy. To do this, we shall first examine the contemporary tradition of radical politics in Iran. Without these references, the current movement, which truly deserves this title, can not be understood correctly.

People, whether consciously or not, are frequently recollecting the 1979 Revolution and the 1997 Reform Movement. Many of their slogans are transformed slogans of the '79 Revolution. The paths of demonstrations are symbolically significantly, the same as those against Shah. But this does not mean that people are imitating the '79 Revolution: there are many new possibilities and creativities, many formal and thematic inventions. As for the 1997 Reform Movement, and its aftermath (the crushing of student protest in 1999), the affinities are even more obvious. Khatami, along with Mir Hossein Mousavi, is one of the most significant leaders and supporters of the protest. It is as if people are trying to redeem the 2nd of Khordad (May 23, 1997), to revive the unfinished hopes and dreams of those days. But this time, the protest is by no means limited to students and intellectuals. Although Khatami in 1997 was elected with 20 million votes from the most varied sections of the nation, the movement was characterized by the political and cultural demands of the middle-class, of students and educated people. But, apart from this, what is the true significance of the 2nd of Khordad Front for politics in Iran?

On the 2nd of Khordad, for the first time since Iranian Revolution, we were encountering a dichotomy between the state and the total system of Islamic Republic of Iran, known as Nezam (System, which is based on the principle of Velayat-e-Faghih, the supreme authority of high-ranked Mullahs). This duality was partly due to the fact that the leader of the opposition, Khatami, was at the same time the chief of the state. It was the only occasion where this duality, which is, in a sense, one between the development of productive forces and cultural, political backwardness, between secular democracy and religious fanaticism, could be revealed. Before and after that period, the state and Nezam have been basically in accordance, as it had been in the Shah's Regime. One of the reasons, if not the main reason, why elections in Iran are of such importance for democratic movements, despite trends to boycott them, lies precisely in the significance of this very duality. Seen from a classical-Marxist perspective, in order to pave the way for the development of productive forces, in order to accomplish the âcivilizing missionâ of capitalism, there must emerge a bourgeois state capable of carrying out the process of democratization and modernization. Whenever the state has been in full accordance with Nezam, this process fails to go on.

Besides this, we deal with yet another duality, one between the capital and the state, the former as the means of development (with all its discontents, aptly and righteously exposed by the Marxist tradition), and the latter as the organ of regression and anti-modernism. So, the progressive and socialist opposition in Iran are faced with the unprecedented, hard task of fighting in two fronts: against religious fanaticism and the authoritarian factions in a semi-democratic government, and simultaneously against global capitalism and its hegemony by means of the production of wars. In a sense, intelligentsia in Iran are very similar to that of Russia and Germany of 19th century. We are a handful of schizophrenics who are, at one and the same time, against and for progress, development, capitalism, state management and so on. In other words, for us, the Faustian problematic, his tragedy, is formulated in a typically Hamletian way.

This ambivalent attitude (to western civilization) can be characterized by the dialectic of state and politics. We are neither dealing with a pure politics a la Alain Badiou, nor with a classical Marxist politics, exhausted in class struggles, nor with the liberal-democratic politics of human rights, which was, by the way, the dominant discourse of opposition in Iran before Mousavi. Our supposedly radical politics consists of every one of these elements, but is not reducible to any of them. To deploy Agambenâs terminology, it is a politics of people against People, i.e. voiceless, suppressed people, against People officially constructed by the state. The current movement materializes, in many respects, this very politics.

But the question, which has confused the western (left) intelligentsia and has caused the most varied misunderstandings regarding Iran, is whether Ahmadinejad is a leftist, anti-imperialist, anti-privatization, anti-globalization figure. The common answer is a positive one. That is why certain misguided western leftists tend to regard the current mass movement in support of Mir Hossein Mousavi and against Ahmadinejad as the struggle of liberalism against anti-imperialism, of privatization, liberal-democracy against the enemies of global hegemony of America.

The main aim of this article is to expose, to expel this widespread illusion. As regards the other confused camp, the Western, more or less, Islamophobic liberals, who are inclined to identify Ahmadinjad with Al-Qaeda, who refer to Mousavi, because of his Islamic-Republican career in 80âs, as another version of Islamic, anti-democratic Ideology, one could say that they too are caught up in an illusion based on easy Euro-centrist generalizations and lack of familiarity with the Iranian historical context. We should thus answer the simple question: what is actually at the stake? Apart from the triad of French Revolution, the triad of modern emancipatory politics, liberty, equality, fraternity, one could maintain that the main bone of contention in this struggle is precisely politics itself, its life and survival. Our government is called the Islamic Republic of Iran. Now the republican moment, which has always been downgraded by the conservatives, is presently being annihilated. It is precisely through this very outlet that any popular politics, from social movement of dissent and class politics to the defence of human rights, might survive.

Another common approach, no matter how radical, supportive, or conservative, to mass protest in Iran is the following: it is a youth movement, at its best, similar to 68âs student protests. New young generation in Iran, armed with Internet, socialized by social networking sites, tired of Islamic ideology, has awakened, claiming its own way of life, and so on. According to this attitude, which is evoked by a number of journalists, it is only the middle-class intellectuals, students, feminists, and other educated people in large cities who are rallying on the streets, communicating with each other thanks to the internet. What is striking is that the state discourse in Iran widely promotes this very attitude. The ruling elite, based on a populist rhetoric, tends to single out a certain section of the nation and call it the People. The state television, Seda-va-Sima, is the main place where this People is represented, indeed constructed, mostly through the usual populist tactic of one nation versus the evil external enemy who is the cause of all trouble. It presents a unified, pure, integrated image of People, all devoting themselves to Nezam, all law-abiding, religious, etc. This image of People is daily imposed on the masses and inscribed onto the body politic.

Against this formally constructed People, with the state as its formal face, there has come out another people, a subaltern, muted people, claiming its own place, its own part in the political scene. June 2009 Election was a decisive opportunity for this people to declare itself, in the figure of Mousavi, who from the beginning insisted on peopleâs dignity as a true political right. But why him? Why not, say, Karroubi, the other reformist candidate? Has Mousvai, now the leader of the mass movement, appeared on the scene in a purely contingent way? Has he by mere chance, by force of circumstances, as it were, become the leading figure, the reform-freedom-democracy incarnate? The answer is positively negative. To elucidate this, we have to draw attention to the tradition from which he has emerged and to which he has repeatedly referred during his electoral campaign. As we said before, this tradition is rooted in 1979 Revolution and has been revived in the 2th of Khordad Movement -- whereas, Karroubiâs âpoliticsâ was based on a subjectless process in which different identity groups would present their demands to the almighty state and act as its passive, divided, depoliticized supporters. In fact, Karroubiâs campaign, with its appeal to Western media, using the word âchangeâ in English, and profiting from celebrity figures, was the one that could be called a Western liberal human-rights-loving, even pro-capitalist movement. The fact that millions transcending their identity and immediate interests joined a typically universal militant politics by risking their lives in defence of Mousavi and their dignity, should be enough to cast out all doubts or misguided pseudo-leftist dogmas.

Morad Farhadpour and Omid Mehrgan [translators and philosophers based in Tehran]

June 30, 2009

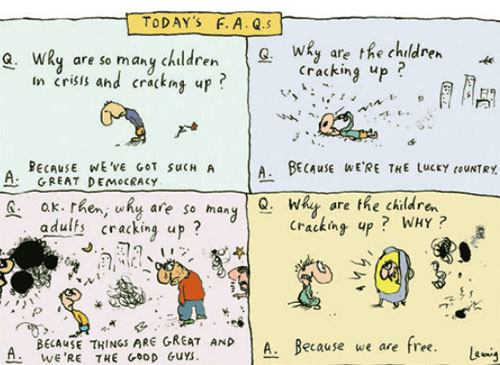

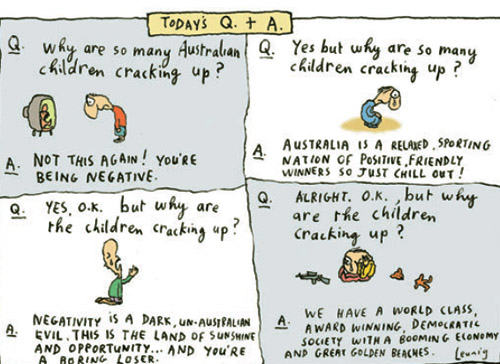

democrat deficit

In this post at public opinion I wrote:

For the Greenhouse mafia the effective operation of a democratic political system requires some measure of apathy and non-involvement on the part of some individuals and groups. For them a crisis of democracy can occur when the populace becomes too well-informed about the true goals and motivations of its politicians, government and corporations. Participatory democracy and active citizenship are to be resisted because limits need to be placed on popular sovereignty in order to remove people from decision-making.

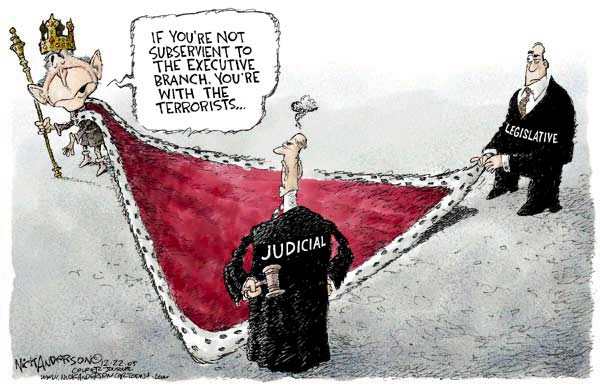

The other side of this democratic deficit is the increasing power of the executive branch in contemporary democracies, and the corresponding loss of power by the legislature. Saskia Sassen in The new executive politics: a democratic challenge at Open Democracy says that this trend of the entrenchment of executive power and its deepening asymmetry with legislative authority is evident across western-style liberal democracies, is the result of a deep process at work that begins in the 1980s with the implementation of neo-liberal policies across historic left-right political divides and can be tracked through six longer-term structural trends. These are structural developments within the liberal state resulting from the implementation of a global corporate economy.

The first trend is the growing power of particular state agencies because of corporate economic globalisation: the treasury, the federal reserve, the office of the trade representative, and other agencies in the case of the US. These and equivalent institutions in other countries played a major role in building this global corporate economy - it was not just an achievement of "the free market". Their growing power in turn empowered the executive branch.

The second trend is that the policies associated with this incorporation of national economies into the global corporate economy (deregulation and privatisation):

on the one hand remove various oversight functions from legislatures, and on the other actually add power to the executive branch. This power gain happens through the establishment of specialised commissions for finance, telecommunications, trade policy, and the other key building-blocks of the new economy. In other words, the oversight functions lost by congress reappear as specialised commissions, mostly staffed by people from the concerned industries in the private sector.

The third trend is that intergovernmental networks centred largely in the executive branch have grown well beyond matters of global security and criminality.

The participation by the state in the implementation of a worldwide economic system has engendered a range of new types of cross-border collaborations among specialised government agencies; these focus on the globalisation of capital markets, international standards of all sorts, competition policy, guarantees of contract for global firms, and the new trade order.

The fourth trend is the major global regulators - notably the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organisation, as well as many lesser known ones - negotiate only with the executive branch.

As the global corporate economy began to grow from the 1980s, these global regulators (pre-existing, or emerging) gained enormous power. This too was a dynamic and self-reinforcing process. By around 2006, when corporate globalisation had been more or less completed, their power was beginning to wane. But the institutional changes that had consolidated the executive branch were in place - and most (such as the specialised commissions referred to above) are there still.

The fifth trend is that a critical component of post-1980s economic deregulation is the privatisation of formerly public functions (such as prisons and the outsourcing of some welfare functions to private providers) The results is to reduce the oversight role of the legislature while increasing that of the executive branch through specialised commissions. The sixth trend is the alignment of the executive with global corporate logics in a range of domains.

Though the neo-liberal model may have been discredited by the financial implosion of 2007-09,it has had profound effects on the internal operations of national states in that our political institutions give the public little, if any, real influence over policy. Colin Crouch argues that we have now entered an epoch of âpost-democracy', within which the established institutions of democratic representation do not function to represent or to enact effectively the collective will of the citizenry.

While modern democracies are keeping up the facade of formal democratic principles, politics and government are increasingly slipping back into the control of corporate elites in the manner characteristic of pre-democratic times.

May 11, 2009

democracy undermined

Norman Abjorensen in Theirs or Ours on Inside Story says that though the Rudd Government's decision to defer its emissions trading scheme- ---delayed by twelve months to July 2011 and the big-polluting exporters receiving more compensation to help them adjust--- is probably good pragmatic politics on the part of the prime minister, it it is clear that the government has buckled to some powerful lobbying and some employment pressure that might be construed as blackmail. He adds:

The real losers, however, are the environment and the people. A less obvious, but equally important, loser in all of this is our increasingly enfeebled democracy â once again trashed by the corporate juggernaut.

This just one more example of what the American political scientist, Carl Boggs, has called the corporate colonisation of society. A deal has been struck between self-interested business elites and a supposedly representative government that has effectively capitulated: the public â and the public interest â have simply been excluded from the equation.

He adds that the current hiatus, made under the convenient guise of the global recession, is merely a continuation of resistance by business to the very problem it has caused and singularly failed to address:

By the late 1990s, verifiable and reputable scientific research had demonstrated the clear and present danger of global warming. The response from business was first to seek to obfuscate with a manufactured scepticism, disputing even the existence of the problem, and then to hijack governments and seek to discredit, marginalise and silence public interest advocates for urgent and drastic action....It is part, in a far broader sense, of capitalismâs greatest triumph, which is not the generation of abundance so much as its effective depoliticisation â and with that its removal from any form of public accountability or influence.

Th is kind of deal being done between government and business over the heads of the people has implications for democracy. It is not just that governments â ostensibly elected by and accountable to the people â are powerless in the face of business self-interest intransigence, but that the real public interest on climate change is without a voice.

December 23, 2008

Australia's compulsory "clean feed" on all internet subscribers

China's reimposition of censorship on websites run by the BBC and other news organisations and other politically unacceptable content is held to be a matter of international concern. Only repressive countries (China, Burma, Cuba, Egypt) restrict Web access and Internet freedom is the argument.

Authoritarian regimes censor web content, encourage self-censorship, demand real-name registration, actively surveil and block online communications, and even limit Internet access altogether. They also punish activists who attempt to use the Internet as a medium to dissent or challenge state authority.

Yet the Rudd Government in Australia is planning to do the same with child porn and illegal and inappropriate material. Inappropriate content, from what we can judge, includes gambling and euthanasia sites plus peer-to-peer file transfers. No other democracy has comparable mandatory internet censorship of this kind --presumably because secret, unaccountable, censorship is incompatible with democracy. It represents a denial of the marketplace of ideas.

As Irene Graham points out

Unlike Australia's offline censorship regime, the Internet censorship regime is secret and unaccountable. Offline material is classified by the Classification Board, an independent statutory body comprising publicly named members.Titles of banned and classified material are publicly available in the Board's online database. In stark contrast, decisions to add content hosted outside Australia to ACMA's blacklist are made by unnamed government agency (ACMA) staff and all information about material on ACMA's blacklist is secret. Freedom of Information legislation was changed in 2003 to exempt all such information from disclosure under FOI (changes voted against by Labor).

November 17, 2008

the internet, agora, Obama

Geordie Williamson in his All Together Now in the Weekend Australian Review argues that the use of the internet in the US presidential campaign has reinvigorated the ethos of the town square. He says:

Never before has a technology proved itself capable of replacing the town halls and city squares that, since the early democratic experiments in the Greek city states of antiquity, have provided the civic space where information is transmitted and ideas are debated, from politics to economics, science to philosophy, by flesh and blood individuals. Developments such as these have inspired pundits from Bill Gates to Wired's founder Louis Rossetto to hail the rise of a digital agora (the ancient Greek term for a place of civic congregation) and to prophesy its revolutionary implications for politics and pretty much everything else.

However, he says that what he saw where crowds of real people, gathered together in often very large numbers, despite delays and physical inconvenience:

to hear a man speak using rhetorical models outlined by Aristotle 24 centuries ago.During the past months, and at no time more than on election night, these crowds have assembled in stubborn resistance to the phenomenon that, we are told, has relegated real-world political rallies to window-dressing for the network news....., the city-sized crowds he [Obama] has attracted, are also a mass indication that the internet, far from supplanting the old-fashioned public realm, has reinvigorated it.

He adds that throughout Australia and across the world, in both qualitative and quantitative terms, public lectures and debates, symposiums and supper-clubs, readings and festivals have exploded in popularity and vigour. They represent an unscripted, unplugged antidote to the theatre that passes for political and cultural discourse in the televisual and online universe.

Let's grant this. What is its significance? To answer, Williamson turns to Seigel's Against the Machine where he argues that the internet produces loneliness which has become a defining condition of our recent history. Williamson turns to Mark Poster's Information Please, where it is argued that the internet radically destabilises identity, is a "a poor substitute for face-to-face contact", and is a space where rational argument rarely prevails and achieving consensus is widely seen as impossible. Williamson then asks:

Could it be that one of the Obama campaign's achievements has actually lain in realising the internet's limitations before the rest of us? That, while the campaign has harnessed those aspects of the technology that would aid it -- fundraising and logistics, say -- Obama has really been running against the loneliness it engenders, the angry echo chambers it endlessly replicates, the human communities that it collapses and degrades?

Williamson argues in the affirmative as the real action is in the world. So on election day he closed his laptopand headed to a public place to stand amongfriends and like-minded others.

August 8, 2008

internet + transparency of governance

Some of the papers that form the Publius Project are very informative. Ellen Miller's Of, By, For and Open to the People is concerned with greater government transparency and accountability. Miller rightly says that information is the currency of democracy and that transparency in the work of government is an invaluable step towards establishing public trust. She observes:

Unfortunately, today we have the opposite. All too often, special interests influence the legislative and regulatory process, breeding public mistrust and cynicism. Much of the lobbying and influence peddling â whether in Congress or the Executive Branch â is carried out in secret, and the laws requiring disclosure are woefully inadequate.

This is similar in Australia where governments and the bureaucracy have devised a myriad of ways to circumvent freedom of information laws to ensure that a culture of secrecy and impunity remains. This secrecy is being reinforced by the ever increasing surveillance of the national security state.

Miller says that this situation of closed walls and doors will begin to change:

As a result of information technology, for the first time in history government has the ability to conduct its business with extensive openness and transparency. In this networked age, we are increasingly communicating, sharing and collaborating with each other in radically new and powerful ways. The information technology revolution will impact and transform our society as profoundly as the printing press did 500-years ago, and radio and TV did in the last century...The changes coming will be fundamental, radical, and profound. The constantly-evolving Internet is enabling a highly-networked world of Web sites, wikis, and blogs making thorough and accurate information dissemination and collection happen at lightning speed.

She quotes Lawrence Lessig's view that this picture points to the next great hope for the information revolution: that we might be able to learn as much about governments and business as they have learned about us. That this might be the end of their effective privacy, just as it has effectively been the end of ours.

June 8, 2008

neo-liberalism

Pierre Bourdieu in his Acts of Resistance (New York: Free Press, 1989), describes neo-liberalism thus:

A new kind of conservative revolution [which] appeals to progress, reason and science (economics in this case) to justify the restoration and so tries to write off progressive thought and action as archaic. It sets up as the norm of all practices, and therefore as ideal rules, the real regularities of the economic world abandoned to its own logic, the so-called laws of the market. It reifies and glorifies the reign of what are called the financial markets, in other words the return to a kind of radical capitalism, with no other law than that of maximum profit, an unfettered capitalism without any disguise, but rationalized, pushed to the limit of its economic efficacy by the introduction of modern forms of domination, such as âbusiness administrationâ, and techniques of manipulation, such as market research and advertising. (p. 35 )

The core belief is that the market should be the organizing principle for all political, social, and economic decisions, neoliberalism wages an incessant attack on democracy, public institutions, public goods, and non-commodified values. Under neoliberalism everything either is for sale or is plundered for profit.

A democratic resistance to neo-liberalism holds that democracy in this view is not limited to the struggle over economic resources and power; since it also includes the creation of public spheres where individuals can be educated as political agents equipped with the skills, capacities and knowledge they need to perform as autonomous political agents.

One institution that provides such a space is the university, a site that, incompletely and imperfectly, sought to educate individuals to be self-critical and independent thinkers as well as participants in a just and democratic society. However, things have changed.

As Henry A. Giroux observes in his Higher Education under Siege:Implications for Public Intellectuals theory is now treated

less as a resource to inform public debate,address the demands of civic engagement, and expand the critical capacities of students to become social agents, theory degenerates into a performance for a small coterie of academics happily ensconced in a professionalized, gated community marked by linguistic privatization, indifference to translating private issues into public concerns, and a refusal to connect the acquisition of theoretical skills to the exercise of social power....This retreat from public engagement on the part of many academics is increasingly lamentable as the space of official politics seems to grow more and more corrupt, inhabited by ideologues and a deep disdain for debate, dialogue, and democracy itself.

April 1, 2008

liberal democracy + climate change

Are we in a 20 year-long (or more) political experiment that will hollow out public life and corrode or destroy "public capital"? One where the notion of the public realm has been corroded by individualist, marketised ideology? A world where the relationship between the individual and government is characterised by widespread low levels of trust in government in a democratic state. Is Rudd simply Blair 2.0, to be it crudely?

These questions are suggested by Guy Rundle's op- ed in The Age, where he argued that the Rudd Government, which was always going to be a cautious centre-right government, is creating a style of government that is openly anti-democratic. My concern arises from why the liberal democracies are being so slow in tackling climate change.

If the trajectory appears to be one of the privatisation, enclosure and the withering of the public sphere, then are our democratic structures up to the task of addressing climate change? Could we say that a fundamental problem causing environmental destruction--and climate change in particular--is the operation of liberal democracy? The argument would be that liberal democracy's flaws and contradictions bestow upon government--and its institutions, laws, and the markets and corporations that provide its sustenance--an inability to make decisions that could provide a sustainable society.

Al Gore, when introducing the British premiere of An Inconvenient Truth in Edinburgh in August 2006, addressed this issue:

In order to solve the climate crisis we have to address the democracy crisis. Especially in the US. I believe that in all democracies the conversation of democracy has been crimped and squeezed into little television soundbites and 30 second commercials. And as a result, people, average citizens, voters, have been pushed out of the conversation. A politics based on the public interest in the future dimension requires a very high level of ideas, in the political dialogue. Of course the Scottish Enlightenment was the epicentre of that kind of politics. It transformed the world. It started here

He added that the Enlightenment and particularly the Scottish Enlightenment enshrined a new sovereign â the rule of reason - and questions of fact were no longer questions of power. They were questions to be answered by the body politic, using the best evidence and the rule of reason, and free debate with an implicit shared goal of finding the right answer for the best policy.

This is not happening today in either Bush America, Brown UK or Rudd's Australia. Gore, however, is fairly upbeat. He says:

I believe that a campaign thatâs based on a very large set of ideas focused on the future and the public interest now faces such a withering headwind that a higher priority is to change democracy and open it up again to citizens â to air it out â and to democratise the dominant medium of television, which has been a form of information flow that has stultified modern life.

Can this public sphere be opened up again and democracy revitalised? I do not think that this will come television in Australia--it is more likely to come from the Internet.

February 24, 2008

public culture + democracy

If "public culture" is often perceived to be under threat from processes of globalisation, the effects of new technologies and the privatisation of public utilities, then twenty-first century technologies have changed the contours of existing public spheres and produced virtual communities. So how have they changed the public sphere around our democratic institutions?

The standard narrative is one of a crisis of disengagement from politics, a disappointment with politics and a turning away from our political institutions. Canberra or Washington isn't working is the public feeling. There is a disconnect between what we do in our personal lives and in collective lives as citizens. Global warming is a good example.

Liberal democracy looks sickly and this malaise of democracy is often expressed in the decline of

participation and the decline of the public.The centralisation of decision-making at a federal and state level has made government remote from citizens, and the rewards from participation increasingly slim, because theprospect of having any influence on decisions is so small. The effectivenessof representation has been increasingly questioned. The sense ofpowerlessness which citizens have when confronted by the modern state contributes to a mood of fatalism and cynicism where public policy is concerned.

Andrew Gamble says that there has been a marked shrinking of the public domain, in the sense of a weakening of the public ethos and the idea of public service. A public domain:

is not the same as a public sector, and is not to be measured simply by the

services directly controlled and provided by the government, or by the proportion of the national income taxed and spent by the state. The public domain is a political space, overlapping both state and civil society, and sustained by particular institutions among which the universities and the media are particularly important. It is a space where the public interest can be determined through debate and deliberation, a public ethos generated, and a public ethic articulated. Independent, critical intellectual work is essential for it, and those who perform that work are public intellectuals. If the public domain is today in trouble, it is because the kind of intellectual work which public intellectuals have performed in the past is less common than it once was, and increasingly under threat.

The public domain has always been vulnerable to erosion, depending as t does on sustaining a public ethos, a set of norms and values indicating how public affairs should be conducted and how the public interest should be determined.

February 19, 2008

democracy, blogging, gatekeeping

In the introduction to the forthcoming International Blogging, edited by Adrienne Russell and Nabil Echchaibi Adrienne Russell says that:

To many, the spread of the American blogging model around the worldâincluding its norms and practices and modes of operationâeffectively represents the spread of democracy. The rhetoric that surrounds blogging essentially describes the liberating potential of a new (American) cultural product, created and distributed globally through inherently democratizing digital tools and networks. More specifically, a rash of recent works outlines the emergence of a new more horizontal politics and journalism driven by blogs and the networks blogs seem to engender.... These works mostly derive from compelling anecdotal evidence but also mostly overlook or ignore the ways power dynamics offline influence developments online. There remains generally a crucial lack of integration in new-media studies between online and offline realities. The theoretical links scholars have been forging, myself included, between democracy and the internet generally and blogs in particular form the great bulk of popular as well as official thinking, obscuring variable contexts and hemming in larger realities.

Recent writing on the liberatory potential of digital media constitutes the latest chapter in the promotion in the West of media as perhaps the key tool in the spread of democracy.

Russell adds:

Digital communication in general has been touted for its independence relative to mass communication, its lack of gatekeepers, its mostly unmediated network qualities. ...Discussion of blogging takes this thinking to new levels. Blogging is celebrated as extended public journaling, pure multimedia freedom of expression, produced anywhere in the world there is internet access and available for eyeballs the world over to take in. The democratic character of blogging is accepted as inherent, the very essence of both the act and the product, the starting point of any larger discussion.Blogs are seen as part of, even perhaps fueling, a trend toward more outspoken, unruly, and mobilized publics, even if the manner in which these publics are being received is accepted as highly contextual

In the blogosphere, as on the internet more generally, new forms of gatekeeping have arisen and new sets of skills are becoming established practice, the prerequisites for entree into the realm of those with power on the web.

February 18, 2008

The Australian's search for credibility

A recent editorial in The Australian opens with the sentence it's time to restore civility to the national discourse. This must be an attempt by The Australian to retain some credibility and influence in the new political order when its motley bully boy crew of right-wing commentators and editorialists has spent a decade sinking the boot into the left and introducing toxicity into public debate. That was then, this is now:

The culture wars are over, at least in the minds of some prominent ABC commentators and the liberal intelligentsia who claim Kevin Rudd has routed the reactionary forces of the Right. If by culture wars they mean ideological trench warfare in which opponents lob insults, indignation and polemic across a barren, muddy landscape, then we join in the hope that peace has broken out. If on the other hand they mean intelligent, informed and reasoned debate then The Weekend Australian fervently hopes they are mistaken.

Hopes? It was The Australian that engaged in trench warfare in which its attack dog commentators lobbed insults, indignation, polemic and engaged in character assassination across a barren, muddy landscape of the public sphere.

Why is this reversal? Why the sudden concern with civic discourse and democracy? The editorial says that Rudd is Howard-lite:

The truth is that Mr Rudd is more than just a fiscal conservative. He is a church-going, family-values social conservative who in many ways has more in common with former prime minister John Howard than, for example, he has with Phillip Adams. Mr Rudd's economic policy is no doubt distasteful to Professor Manne, who has been an ardent critic of economic rationalism. What the election of Mr Rudd has done is make many conservative policies and values less easy for the Left to attack.

Rudd's election represents another defeat for the left. However, the signs----Kyoto and the apology-- are that Rudd is moving away from his me-too electoral persona of Howard-lite. If The Australian now endorses Kyoto and the apology because these are merely symbolic, then they are swallowing a lot of their own history of entrenched opposition to both. What they are disguising is the extent of shift they had to make in their rewriting of history to gain credibility in a new political order.

The second reason in The Australians call for a new spirit of reconciliation and the restoration of civility to the national discourse:

Lastly, while the internet has democratised access to the public arena, it has also coarsened debate. We admit we have not been above the odd ad hominem attack ourselves. It's time for a little more elegance, a return to the debating conventions of earlier times, to the rules obeyed by men and women of letters. As we prepare for the 2020 summit, let's return civility to the national conversation. We should be able to respect our opponents even when we disagree with their ideas, counter them with argument, not argumentativeness. It would make a welcome change to emulate a little more of the Age of Enlightenment, a little less of the Reign of Terror, a little more of the spirit of the salon, a little less of the barricades. It's time for a battle waged with wit, not brickbats.

The bloggers are to blame for the polemics of tench warfare, with The Australian admitting that it has merely engaged in odd ad hominem attack. So it is positioning itself as the reasoned salon voice of the Enlightenment against the terror wagged by the lefty bloggers. Presumably, the Australian will continue to affirm the values of western civilisation against the romanticisation of the

noble savage.

This revisionism fails to persuade. The blood stains of the culture wars waged by the attack-dog journalists exist because the young conservatives go beyond robust debate in the public sphere on a controversial subject. They deploy tactics of personal denigration that is designed to discredit an opponent and who use the term 'political correctness' to attack universities and whole disciplines whilst lecturing everyone on patriotism. Tenured radicals were said to have imposed a tyranny of political correctness in the academy, victimising dissident colleagues, imposing restrictive speech codes, rooting out all elements of the traditional canon and poisoning young minds with their obscure and nihilistic theory.

January 31, 2008

media, democracy, power

In The blind newsmaker at Open Democracy Tony Curzon Price says that the mass industrial media, at their best, perform two basic public functions. First, they monitor and hold to account, and second, they form and maintain a common purpose, an ``imaginary community''. These are ``negative'' and ``positive'' tasks: avoiding the worst excesses of power and rule by experts; and defining and sustaining a common good.

This is the public role of the media as the watchdog for democracy in a nation-state view. Behind this stands the history of nation building, the peoples voice, nationality, freedom of the press and professionalism journalism with its ethos of objectivity and neutrality. This constellation is decaying and it is generally held that the press fell asleep at the wheel after 9/11 as they failed to ask the tough questions. Fox News is the new kind of media.

Price notes the decline of the mainstream media in a digital age-- due to dropping circulation and print advertising revenue falling---and he asks:

Techno-optimists believe that the hyper-modularity of the future of news-making will allow us to re-assemble whatever value was produced in the old system. But the two essential public functions of the news are inherently the products of un-fragmented processes. The troubling question becomes: who will protect us from the excesses of power? and what sorts of common projects and shared identities will flourish in the fragmentary world? What power will we permit to emerge, and who will we become?

Alan Rusbridger, editor of The Guardian, argues as a paper-optimist that the old institutions will simply transfer online, and that revenues online will rise fast enough for the old model of production to survive.

The Guardian looks as if it is able to deliver whilst The New York Times is struggling to find a viable business model after its experiment with a subscription wall failed and the hedge finds are circling.

Price argues that all the components of the newspaper's two core functions will continue to be produced, often in a very fragmented way. He mentions the Security Council Report for the negative power of speaking truth to power and The Arts And Letters portal as an example of the defining and sustaining a common good function.

Update

Is this fragmentation happening in Australia? Yes. The Bulletin magazine has gone --it largely became irrelevant---and Crikey is an example of the formation of digitally based watchdog truth to power, even though this is not recognized as professional journalism. The ABC, as the national broadcaster, looks as if it is able to follow the Guardian or BBC pathway to a viable digital presence.

January 23, 2008

Bourdieu + collective intellectual

The latter Bourdieu is the one that I do know: the Bourdieu, who, when faced with governmental policies eroding the welfare state in France, turns into an outspoken public critic of neo-liberalism, globalization, market-oriented reforms and privatisation. This shift into the public intellectual is documented in the collectively authored work under his direction titled The Weight of the World (1993) and it gives rise the idea of the âcollective intellectualâ. The âcollective intellectualâ, according to Ulrich Oslender, in The Resurfacing of the Public Intellectual: Towards the Proliferation of Public Spaces of Critical Intervention in ACME is a:

....series of critical networks made up of âspecific intellectualsâ that oppose the production and imposition of a neo-liberal ideology promoted by conservative think tanks and âexpertsâ in the service of Capital...The collective intellectual has two functions: firstly, a negative (i.e. defensive) one, critiquing and

working towards the diffusion of tools to defend against dominant power discourse; and secondly, a positive (i.e. constructive) one that contributes to a collectively perceived political re-invention and political and economic alternatives. At the ame time it is a call for the collective organization of intellectuals, a form of

intellectual militancy that defines an activist strategy for an intellectual field threatened by public policy discussion and formulations that have become framed by neo-liberal economic assumptions.

This usefully shifts the emphasis away from challenges the commonplace assumption of the production of intellectual thought as an individual enterprise to the structured networks, connections, alliances and linked-up solidarities takes into account the multiple sites in which intellectuals participate.

December 31, 2007

revisiting populism

Ivan Krastev opens his article The populist moment at Eurozine with the phrase 'A spectre is haunting the world: populism', and then adds that it is unclear just what populism is:

On the one hand, the concept of "populism" goes back to the American farmers' protest movement at the end of the nineteenth century; on the other, to Russia's narodniki around the same period. Later, the concept was used to describe the elusive nature of the political regimes in the Third World countries governed by charismatic leaders, applied above all to Latin American politics in the 1960s and 1970s. ....Clearly, populism has lost its original ideological meaning as the expression of agrarian radicalism. Populism is too eclectic to be an ideology in the way that liberalism, socialism, or conservatism are. But growing interest in populism has captured the major trend of the modern political world â the rise of democratic illiberalism

December 30, 2007

Rorty: philosophy & democracy

Richard Rorty, as is well known, argues for the irrelevance of philosophy to democracy. He does in terms of a historical argument. He says at Eurozine that:

Philosophy is a ladder that Western political thinking climbed up, and then shoved aside. Starting in the seventeenth century, philosophy played an important role in clearing the way for the establishment of democratic institutions in the West. It did so by secularizing political thinking â substituting questions about how human beings could lead happier lives for questions about how God's will might be done. Philosophers suggested that people should just put religious revelation to one side, at least for political purposes, and act as if human beings were on their own â free to shape their own laws and their own institutions to suit their felt needs, free to make a fresh start.

He adds that the eighteenth century, during the European Enlightenment, differences between political institutions, and movements of political opinion, reflected different philosophical views. Those sympathetic to the old regime were less likely to be materialistic atheists than were the people who wanted revolutionary social change.But now that:

... Enlightenment values are pretty much taken for granted throughout the West, this is no longer the case. Nowadays politics leads the way, and philosophy tags along behind. One first decides on a political outlook and then, if one has a taste for that sort of thing, looks for philosophical backup. But such a taste is optional, and rather uncommon. Most Western intellectuals know little about philosophy, and care still less. In their eyes, thinking that political proposals reflect philosophical convictions is like thinking that the tail wags the dog.

The philosophical justification for this position is anti-foundationalism; the view that contests the claim of Enlightenment rationalism that there is something above and beyond human history that can sit in judgment on that history.

Rorty says:

anti-foundationalists like myself agree with Hegel that Kant's categorical imperative is an empty abstraction until it is filled up with the sort of concrete detail that only historical experience can provide. We say the same about Jefferson's claim about self-evident human rights. On our view, moral principles are never more than ways of summing up a certain body of experience. To call them "a priori" or "self-evident" is to persist in using Plato's utterly misleading analogy between moral certainty and mathematical certainty.

To say that a statement is self-evident is, Rorty the anti-foundationalists argues, is merely an empty rhetorical gesture. The existence of the rights that the revolutionaries of the eighteenth century claimed for all human beings had not been evident to most European thinkers in the previous thousand years. That their existence seems self-evident to Americans and Europeans two hundred-odd years after they were first asserted is to be explained by culture-specific indoctrination rather than by a sort of connaturality between the human mind and moral truth.

December 18, 2007

The Internet as the fifth estate?

The media are often seen as central to democratic processes: a 'fourth estate ' independent of government and other powerful institutions. Today, however, the Internet and Web are creating a new space for networking people, information and other resources. Does this network of networks have the potential to become an equally important 'fifth estate' which could support greater accountability in politics and the media. Is this plausible? How does this develop the idea of a public sphere? How is the fifth estate different from the fourth estate?

I have come as far as seeing that the Internet is a new kind of space and one that is different from that of the traditional mass media, even when they (News Corp, ABC, Fairfax) step into this space to support their traditional activities. But what kind of space is this new space? In his inaugral lecture as Director of the Oxford Internet Institute William H Dutton develops the idea of the internet as fifth estate. That's a novel idea as it builds on the capacity of advocacy and in its implicit ability to frame political issues.

If society is governed by the predicts: judiciary, executive and parliament, then as Edmund Burke, observed by pointing to the press gallery in British Parliament and exclaiming "and this is the Fourth Estate". Ever since, the term 'Fourth Estate' has represented the media's role as a watchdog of the bureucracy and government by exposing corruption and unfair dealings with complete transparency. Is this what Dutton has in mind when he refers to the fitth estate?

He says:

Some have argued that the Internet is essentially a new medium similar to the traditional media. This has led to a view of the Internet as an adjunct of an evolving Fourth Estate. Others see elements of the Internet â such as the citizen journalist or the blogger â as composing a kind of Fifth Estate. However, both conceptions are tied to an overly limited notion of new digital media as being just a complementary form of news publishing. The Internet is far more than a blogosphere or online digital add-on to the mass media.

Rightly said. Just think of Flickr or Facebook, downloading music or video, or the way people use the Internet to make new friends and, thereby, reconfigure their social networks. This is no passing blogging fad.

Dutton says that internet-enabled, networked individuals often break from existing organizational and institutional networks that are themselves being transformed in Internet space. A good example is internet-enabled, networked individuals breaking away from the walled universities. Dutton adds:

The ability the Internet affords individuals to network within and beyond various institutional arenas in ways that can enhance and reinforce the âcommunicative powerâ of ânetworked individualsâ is key. The interplay of change within and between such individual and institutional ânetworks of networksâ lies at the heart of what I am arguing is a distinctive and significant new Fifth Estate.

By enabling a huge range of people across the globe to reconfigure their access to information, people, services and technologies, the Internet and related ICTs have the potential to reshape the communicative power of individuals and groups in numerous ways. But how does this become a fifth estate?

Dutton's argument for this is that people are using the internet for information, have found ways to trust that information through experience (eg. Wikipedia), and that the Internet is crucially enabling individuals to network in new ways that reconfigure and enhance their communicative power. He mentions the media, politics, government online, the workplace and the business firm (eg., Internet-enabled networks that come together to solve a problem) education and research. From this Dutton infers that:

the Internet is becoming not only a new source of information, but also a platform for networking individuals in new Internet-enabled groups that can challenge the influence of other, more established, bases of institutional authority. Moreover, it is robust. As discussed, it can flourish despite a digital divide in access. And it can be a significant force even though only a minority of users are actively producing material for the Internet, as opposed to simply using it.

Duttn acknowledges that the role of the Internet â and of networked individuals â is not uniformly positive, since the open gates of the Internet, which allow in those aspects of the outside world of benefit to the user, also allow those causing harm by intent or accident, including spammers, fraudsters, pornographers, bullies, terrorists, and more.

Dutton's conceptualization of the Fifth Estate turns away from Edmund Burke to Manuel Castells to develop the fifth estate as creating a space of flows, in contrast to a space of places. When you âgo toâ the Internet, you enter this new space of flows that connects with people and places. This is dramatically different from a physical place, such as this hall. Both are important. Both serve major social roles in shaping the quality of our information environment and they complement one another. Dutton adds:

This space of flows enables a multitude of actors to reconfigure access to information, people, services and technologies.....A key implication of this for society at large is that the Internet can be used to increase the accountability of the other Estates, for instance by being used as a check on the press. It can also be deployed as an alternative source of authority and as a check on other established positions of authority, such as politicians, doctors and academics, by offering alternative sources of information, analysis and opinion to citizens, patients, and students.

Thus through the space of flows, the network of networks, the Internet is enabling the development of a Fifth Estate that is enhancing the accountability of many sectors across all societies is the argument.

December 14, 2007

violent democracies

In Democracy's Violent Heart a review of Daniel Ross' Violent Democracy in Borderlands Mathew Sharpe says that Ross brings to contemporary Australian political debates:

resources from traditions in continental European thinking that are usually disregardedâwhen they are not dismissedâin the Australian public sphere. By doing so, Ross' book invites a wider, non-philosophical audience to raise far-reaching and deeper questions about the nature of politics. In particular, as Violent Democracy 's title suggests, Ross's concern is with how and why our political life always seemingly involves violence, whether this is inevitable, and what can and ought to be done about it....The argument of Violent Democracy challenges from the start any benign ideas we might have inherited that modern democracy is "the solution to the violence of tyranny and chaos".... Ross does not accept the story that liberal democracy is that political system which, historically as today, secures the peace by separating state and public life from people's private passions and religious convictions. For him, all democracies âas political systems that wrest sovereignty from the few and reassign it to 'the people' âhave a "violent heart".

Sharpe adds that Violent Democracy runs two arguments about democracy's "violent heart". The first argument is that "the origin and heart of democracy is essentially violent". There is no democracy without the beheading of the King, or the 'taming' of the frontiers. The book's second contention is that "the violence of democracy has changed, or is unfolding in a certain direction, across the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries". Doesn't any political regimeâwhether tyrannical or democratic or oligarchic, etc.âdepend upon a violent founding act, wherein the new rulers oust the old ones and lay claim to being the people's champion and spokesperson?

The second argument is the one I'm more interested in. Ross argues that since 9/11 it is

not so much war that has changed, but the way in which democracy imagines itself. 'Democracy' seems to be rethinking itself, no longer on the ground of transcendent law based in the sovereignty of a people. Law is reconfigured on the basis that there is an enemy, internal and external, against which it is necessary to act rather than react.

Sharpe says that Ross reads the changes being undertaken by Western democracies in response to the 'war on terror' as highlighting a key tension in the constitution of any democratic polity, between the necessary institutions of "military rule", grounded in the executive authority of the Head of State and "the Law", enforced by the police, and in liberal democracies (since Locke at least) conceived as a means of protecting the people itself "even against" the executive fiat of its leaders.

History since 9/11 would seem to reeinforce Agamben against Foucault: contemporary biopolitics is not superseding or undermining the power of the sovereign. Rather, it is increasingly the corollary of conscious attempts by elements within the liberal democracies of the US, UK and America to re-institute sovereign executive power in the face of changing contemporary circumstances.

October 14, 2007

Democratic Capitalism and Its Discontents

In Democratic Capitalism and Its Discontents â Brian Anderson explores what troubles democratic capitalism today. Anderson is the author of South Park Conservatives: The Revolt Against Liberal Media Bias, which explored the idea that the traditional mass media in the United States are biased against conservatives, but through new media, such as the Internet, cable television, and talk radio, conservatives are slowly gaining some power in the world of information.

In Democratic Capitalism and Its Discontents Anderson defends democratic capitalism from its ideological opponents but also tries to be open-eyed about what existential weaknesses erode democratic capitalist societies from within. In the first chapter he turns to the work of late French historian François Furet, who argued that liberal democracy has two weaknesses. According to Anderson Furet says that the first weakness is that:

liberal democracy had set loose an egalitarian spirit that it could never fully tame. The notion of the universal equality of man, which liberal democracy claims as its foundation, easily becomes subject to egalitarian overbidding. Equality constantly finds itself undermined by the freedoms that the liberal order secures. The liberty to pursue wealth, to seek to better one's condition, to create, to strive for power or achievement-all these freedoms unceasingly generate inequality, since not all people are equally gifted, equally nurtured, equally hardworking, equally lucky. Equality works in democratic capitalist societies like an imaginary horizon, forever retreating as one approaches it.

Liberal democracy prioritizes liberty over equality in a world of the radical plurality of values.

Furet says that:

The second weakness of liberal democracy is more complex, though its consequences are increasingly evident: liberal democracy's moral indeterminacy. The "bourgeois city," as Furet terms it, is morally indeterminate because, basing itself on the sovereign individual, it constitutes itself as a rebellion against, or at least as a downplaying of, any extra-human or ontological dimension that might provide moral direction to life. For all the inestimable benefits of the bourgeois city-its threefold liberation, in Michael Novak's formulation, from tyranny, from the oppression of conscience, and from the pervasive material poverty of the premodern world-its deliverance from the past has come at a price.

Furet suggests that as the "self" moves to the center of the bourgeois world:-- the sovereign individual has been loosened from the thick pre-modern inherited attachments and now lives a life that one wills. All relations and all bonds are voluntary.In this context existential questions----what is man? what is the meaning of life?---become difficult to answer.

September 24, 2007

about populism # 1

One nation conservatism is a defensive reaction to neoliberal globalization that takes the form of populism. Populism has lost its original ideological meaning as the expression of agrarian radicalism. Ivan Krastev says in Eurozine that populism is too eclectic to be an ideology in the way that liberalism, socialism, or conservatism are. But growing interest in populism has captured the major trend of the modern political world â the rise of democratic illiberalism. He adds:

The new populism does not represent a challenge to democracy, understood as free elections or the rule of the majority. Unlike the extremist parties of the 1930s, the new populists do not plan to outlaw elections and introduce dictatorships. In fact, the new populists like elections and, unfortunately, often win them. What they oppose is the representative nature of modern democracies, the protection of the rights of minorities, and the constraints to the sovereignty of the people, a distinctive feature of globalization.

This assumes that populism is right wing. Is there not a populism on the left?

Krastev tries to account for the rise of populism today by the erosion of the liberal consensus that emerged after the end of the Cold War on one hand, and by the rising tensions between democratic majoritarianism and liberal constitutionalism â the two fundamental elements of liberal democratic regimes â on the other. The rise of populism indicates the decline of the attractiveness of liberal solutions in the fields of politics, economy, and culture, and the growing popularity of the politics of exclusion.

September 14, 2007

David Malouf on res publica

David Malouf makes some interesting comments on public spaces and how we are all related to the modern city in a talk to the Brisbane Institute. He says:

We have two lives there, a public life in which we adhere to citizenly values and requirements and which we share with others both in the public space of res publica and in real spaces where we move among strangers as if they were neighbours and feel secure in doing so. How we behave there is other peopleâs business as well as our own. But only there. The other life, the personal, the private life, is entirely our own. There we are free to believe what we please, to hold our own views, follow our own gods and customs, live inside our own culture, even an eclectic one of our own making. The play between the two, public and private, may require delicate negotiations with ourself. But as we see in the case of orthodox Jews for example, or Pentecostals, or Moslems or Buddhists â there are many examples of groups who live apart in one sense and fully among us in another â it is perfectly possible to be integrated without being assimilated, to live richly inside a culture or religion, follow its customs, keep its rules, and still be an active participant in the society at large.