May 31, 2009

once, there was water

Although the commonwealth buy back of over-allocated water licences in the Murray-Darling Basin for environmental flows continues, the lower lakes and the Coorong are slowly drying out from a lack of water flowing down the River Murray. So a weir at Wellington, at the mouth of the lower lakes, is being proposed to secure Adelaide's water security.

What then of the lakes themselves? What becomes of them with no fresh water inflows coming down the River Murray? As they dry out the acid suphate soils become exposed. The worst possible outcome for the lakes is acidification, since acid kills everything. If the lakes acidify, then nothing lives in them. This outcome is increasingly being accepted as a political reality. So what can be done to prevent the process of acidification in Lake Alexandrina and Albert?

Opening the barrages and Flooding the drying lakes with saltwater to prevent acidification has been the main option so far. Another option is bioremediation---- using lime and planting cereal rye to stimulate plant growth, which would mitigate, if not, neutralize the acid sulphate soils.

Space: Trifid Nebula

The Trifid Nebula is a star forming region in the plane of our galaxy and is about 40 light-years across. This image is taken with a SBIG ST4000 color camera:

Ed Henry, Trifid Nebula, Astronomy Picture of the Day

Ed Henry, Trifid Nebula, Astronomy Picture of the Day

Are these kind of space images posted on Flickr? Heaps from a quick look. I guess there would be less camera lust--desire for the ideal camera?--- in these groups. There would be less emphasis on the passion for new technology or the idea that the camera makes the picture.

Camera lust, or techno-lust, is deeply entrenched in photographic culture. The subtext is that the latest DSLR, or the 'need' for new gadgets, will enable the amateur to become the closet professional photographer they desire to be. Becoming a Serious Photographer is all about the technology you use.

The camera and lenses are lusted-for objects, rather than mere tools to take worthwhile pictures. Our culture fetishizes a tool and a fetish as an object or feature of an object functions to solve some need though the user of the object cannot articulate precisely what that need is. A camera becomes a gadget when its basic function---- to take a picture ----overwhelms the user, forcing him or her to select from ten automatic picture-taking modes in order to get a decent image.

Computers, cameras and other electronic junk, called e-waste, are what come of our lust for upgrades to gadgets. This year's new iPod is next year's throwaway; or last year's chunky screen is on its way to the computer crematorium

May 30, 2009

German Photography: Michael Schmidt

The dominance of the the Becher students (Gursky, Ruff, Struth, et al) in the art markets in recent years, it would be easy for collectors to come to the conclusion that everything interesting in German photography was and is emanating from Dusseldorf. The work of Michael Schmidt, is an example of some of the excellent work coming from a group of photographers who have been working in and around Berlin/Essen for decades, with loose ties to Lewis Baltz and Paul Graham.

Michael Schmidt, Berlin-Stadtbilder (Cityscapes) ; 1976-1980.

Michael Schmidt, Berlin-Stadtbilder (Cityscapes) ; 1976-1980.

Schmidt also works in serial format, gathering together sequences of images that together provide a more nuanced view of a subject. This sequence doesn't tell a deeper or more linear narrative or story since it is more the relationships between a group of fragments or moments broadening our understanding of the rhythms of life buried underneath the surface.

A characteristic of his work is the arrangement of the individual photographs — the interplay and dialogue between the multi-layered images — that gives the images their distinct meaning, revealing the correlation between historical events and individual biographies. This leaves his images rather l open for different viewers’ interpretations.

In his photographs of urban architecture, which are not simply physical landscapes but social ones as well, he provides a formally balanced but menacing portrait of the modern metropolis.

Michael Schmidt, Berlin-Wedding; 1976-1978.

Michael Schmidt, Berlin-Wedding; 1976-1978.

In the city landscapes of “Berlin Wedding” (1976-78) the artist offers a seemingly factual account of the district, cast in richly nuanced greys. The photographs show deserted sites with pre-war architecture, empty lots, massive post-war concrete building blocks as well as sporadic patches of urban nature. In a similarly objective style, he registers in “Stadtbilder” (1976-77) the many iterations of former-West Berlin’s architecture. In this way, the architecture itself can be read as an emblem of historical and social processes.

The images for Irgendwo" (Somewhere) from 2001-2004 were taken over the course of three years during Schmidt's extensive journeys through out Germany. The artist has arranged the images in groups of nine photographs for display in the main space of the gallery."Irgendwo" presents rather bleak views of province-life in the reunited Germany with suburban houses and village pubs, deserted low-cost supermarkets and historical buildings, as well as distanced motorways cutting through the landscape.

Typically for his Modus Operandi Schmidt conflates architectural and landscape photographs with portraits and shots of seemingly unimportant details. It is only through the arrangement in groups - the interplay and dialogue between the images - that the individual images acquire their distinct meaning and the issue of a relation between spatial environment and individual biography comes into view.

May 29, 2009

Paul Graham

Paul Graham's photographs exist the space and tensions between photography as documents and photography as visual art. This British photographer works in this space by producing particular bodies of work that are structured in terms of books---the ones that I know are the early ones, such as A1--The Great North Road (1981-82 ) and Troubled Land. (1984-86).

Paul Graham, Beware, from Troubled Land

Paul Graham, Beware, from Troubled Land

These texts connected contemporary colour photography, large format cameras and the classic genre of social documentary whilst transgressing the narrative conventions of photojournalism and the 1980s conventions of art photography (eg., the staging of tableaux). The space is one of making bodies of work (twenty or thirty pictures) where images work together to build up a coherent statement. The book is the work.

In this interview he says:

The important photographers for me belong in that period from 1966 to 1976, mostly American, let’s say from “New Documents” to “New Topographics.” It was a profound creative period for photography. Szarkowski at MoMA radicalized things for photographers by creating an artistic territory to operate in that wasn’t there before. Before, you were either an editorial photographer working for magazines in a semi-documentary style, or a fine-art photographer making pictures of landscapes or nudes or rocks. He swept aside that division and showed that people like Diane Arbus and Garry Winogrand were making the most profound photographic work of our time, and though it looked like ‘documentary,’ it was far more than that, and it didn’t belong in magazines, but in museums. This was transformative: bringing ‘documentary style’ work into the highest museum of our country. It’s little appreciated, but was perhaps Szarkowski’s greatest gift—recognizing and defining a new artistic space.

New Europe was different, as the images were more poetic. Graham had connected with a group of German photographers who were quite distinct from the Becher’s Dusseldorf school, as they were mostly around Essen-Berlin and had ties with Lewis Baltz.

Paul Graham, untitled, from New Europe, 1986-92

Paul Graham, untitled, from New Europe, 1986-92

Michael Schmidt, one of the Essen-Berlin German photographers, works in serial format, gathering together sequences of images that together provide a more nuanced view of a subject . This sequence doesn't tell a deeper or more linear narrative or story since it is more the relationships between a group of fragments or moments broadening our understanding of the rhythms of life buried underneath the surface. Schmidt's images are concerned with the burden of history and the uncertainty of memory. In his photographs of urban architecture, which are not simply physical landscapes but social ones as well, he provides a formally balanced but menacing portrait of the modern metropolis.

Graham's New Europe digs beneath the utopian dream of a united continent arising to face the dawn of the 21st century and reflects on the inescapable shadow of history that falls over each nation's conscience, from the dictatorships of and Hitler and the Holocaust This burden is interwoven with a questioning of the banality of modern day consumption-led culture.

May 27, 2009

Joni Mitchell: The Magdalene Laundries

Joni Mitchell re-recorded this song about sadism in the Catholic church from "Turbulent Indigo" (1994) for an album by the Irish band The Chieftains entitled Heart of Stone 1999

The songs and arrangements of "Turbulent Indigo" recall the pop rock of Court and Spark (1974) and, to a lesser degree, the meditative jazzy style of Hejira (1976).The sosngs are far more melancholy songs as they are about injustice.

Stills Gallery: Thirteen, Robyn Stacey

Stills Gallery in Sydney, Australia, currently has an exhibition entitled Thirteen This provides a selection of work from a wide range of photographic artists ---Thirteen refers to the number of artists--- and, as there is no online exhibition catalogue, it is a matter of dipping in and having a look around.

My interest here is the work of Robyn Stacey. She is a senior lecturer in the School of Communication Arts at the University of Western Sydney and has a fascination with natural history and museum collections.

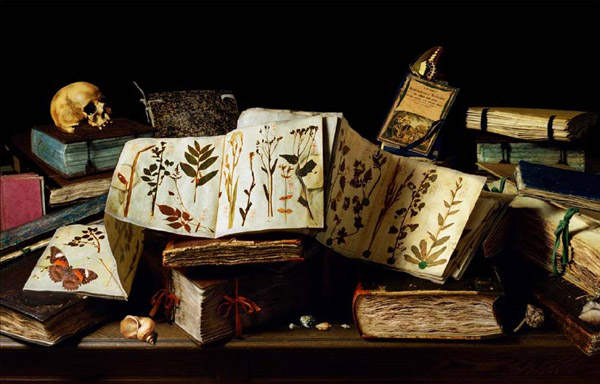

Robyn Stacey, Leidenmaster I, 2003 from The Collectors Nature

Robyn Stacey, Leidenmaster I, 2003 from The Collectors Nature

The images in The Collectors Nature represent the collections of the Sydney-based Macleay Museum and Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney, as well as the National Herbarium of the Netherlands at Leiden. Stacey references Alexander Macleay, the Australian collector who spent his leisure time importing plants from around the world, whilst her compositions of old and rare books of botanical illustrations refer back to the work of Dutch still life painting.

In terms of the photographic histories tentatively mapped in this earlier post Stacey is part of the generation of photomedia artists who came to prominence in the 1980s. These artists were unconcerned with, even suspicious of, the claims to truth by various styles of personal documentary photography dominant in art museums in the 1970s. They turned away from reportage style photography and embraced visual culture as a source rather than the ‘real’ world. The artists of this postmodernist movement happily appropriated images from the past as well as popular culture, including the look of ‘old master’ paintings or fifties and sixties magazines and television.

Stacey’s series works, such as Kiss kiss bang bang 1985 and All the sounds of fear 1990, were grounded in popular culture with a slightly sixties Pop look, but presented a somewhat anxious and edgy contemporary world. By contrast her work since the 1990s has made use of natural science and a number of natural history museum collections in which she worked during several residencies.

May 26, 2009

photographic histories

Australia is a regional culture that normally gets little or no mention outside its own shores--ie in American or Europe. So its recently written history of photography is largely unknown --an art history that is written in terms of a canon of a few master pieces by a limited number of celebrated photographers seen as creative geniuses who have individual styles based on pictorial innovation and power. These regional heroes do not figure in the art or social history of against background of Europe's historical imaginary of Australia as the other of Europe.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, The Adelaide Electric Supply Co, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, The Adelaide Electric Supply Co, 2009

It's the old story of centre and periphery, dependency and innovation within a European vision and the common temptation to see Australia photography from the 1960s onwards as a dependent shadow of American photography. The Australian work is then seen as provincial, not original and formed by cultural subjection. It has an absent presence.

The 1980s is commonly seen by photographic historians such as Helen Ennis, Anne-Marie Willis and Geoffery Batchen -- as a a new beginning for art photography. A rupture from modernism as it were. The art institution----ie., the supportive network of schools, galleries, museums, magazines and public funding-- now had a substantive presence. There was the professionalism of the new generation of artist photographers, the diversity of their backgrounds, the interest in French poststructuralist theory, the emphasis on studio images and the turn away from truth and realism to excess and artifice.

However, if we accept poststructuralism's argument that photography's coming into prominence is broader than art photography. Photographic practices are embedded in a much larger assemblage of events, power relations, institutions and discourse, and these are coupled to the historicisation of vision So we need to broaden our perspective on photography in Australia prior to photography's shift from analogue to digital in the 1990s and the rise of the computers raises the question of the end of photography.

Geffry Batchen in an essay in Each Wild Idea: Writing Photography, History identifies several different photogrpaphies. There was the increasing use of photography as a form of social control by the state (the proposed Australia card and the use of a state driver's licence as a form of identification); the guerrilla campaign against (defacing) the photographic images on advertising billboards by B.U.G.A.U.P., debates over the truthfulness of photographed face of Lindy Chamberlain, the use of wilderness photography by the environmental movement to stop the Franklin dam in Tasmania from being built.

I would add the strong presence of amateur photography--what Geoffrey Batchen calls vernacular photography-- and the desire of photographers to preserve our architectural heritage.

This gives us the intersection of regional and international flows with photographers negotiating these intersections, and in doing so, producing what can be called the regional quality of Australian photography. That regional quality can be identified as the supplement and it needs to be recognized and evaluated in its own terms.

poisonous tv

According to this articlet in The Age there is not a unified television recycling program even though two million old TVs estimated to be offloaded annually to make room for flat screen technology and there is the looming 2010 switchover from analogue to digital. Consequently, millions of old televisions, with poisonous cargo of almost 2kgs of lead and other heavy metals, are finding their way into Australian landfills each year, rather than being recycled.

James Good, Swamp TV, Miama, 2007

James Good, Swamp TV, Miama, 2007

Instead of the cost of recycling falling to the television manufacturers as it does in other countries, the financial and logistical burden rests largely on local governments who must either transport the thousands of discarded or dumped televisions to landfill or, in rare cases, take matters into their own hands by establishing expensive recycling schemes.

May 25, 2009

photography and beauty

One of the central memes in photographic culture is the general acceptance that photography's central concern is beauty-----whether this is interpreted as in terms of aesthetic experience of the viewer or the Platonic idea that beauty is a property of objects that is independent of the viewer's appreciative response. This acceptance of traditional values is at a time when beauty as an artistic value has not been at the centre of art practical or criticism since the mid 20th century.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, storm water, Port Adelaide, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, storm water, Port Adelaide, 2009

Robert Adams in his influential essay "Beauty in Photography” adopts the latter position, when he asserts that “beauty” is another word for the coherence and structure underlying life and the beauty that concerns the artist is one of this structure or “Form" that can help us to meet our worst fear, the suspicion that life may be chaos and that therefore our suffering is without meaning”. Beauty in art (Form) helps us to deal with loss, grief and death in the real world.

This account holds that “art takes liberties to reveal Form”; or imposes an order on the scene though simplifies the jumble by giving the chaos some structure. Order and form (beauty) – is then equated with meaning. The opposite of beauty is chaos, formlessness, and meaninglessness.

There is a lot of support for Adam's position that Beauty is a synonym for the coherence and structure underlying life.” Plato’s definition of beauty – unity, regularity, and simplicity – reflects qualities of our most valued scientific theories when stated in a mathematical form. The archetypes of beauty –geometric patterns of order – are reflected throughout nature: in a snowflake, a leaf, a solar system. Science seeks to understand nature, and when natural patterns of order are revealed, scientists believe they have uncovered a truth.

We can begin to loosen this duality up by remarking that the ugly may be just as true as the beautiful. So may the awful and the sublime, which is characterized by boundlessness and formlessness. If beautiful pictures are not inherently any more true than ugly ones, then many beautiful photographs are manipulated, showing a falsified vision of reality, and so depicting the world through rose colored glasses. National Geographic, for instance, has often been criticized for only presenting the sunnier side of life due to its preference for strikingly beautiful images.

So photographs can still be considered beautiful in form even when the subject matter (the content, eg., the horror of dead in a war) is ugly. A beautiful form is not enough to suggest truth or to reveal meaning, even though form can have meaning. If modernism treats a photograph as an image containing meaning, then postmodernism sees a photograph as a cultural object in a visual culture whose meaning arises from how the photograph is used and written about.

May 24, 2009

photography blogging

According to PhotographyLot the The New York Photo Festival had a panel session on photography and blogging. An excellent example of blogging photographers is Camera Obscura.

Laurel Ptak has an audio of the session A selection of the photographic work at the festival can be found in the special issue of Visura magazine.

PhotographyLot's summary of the photography and blogging panel discussion states:

A few issues were raised – on the fact that the internet has replaced face to face discussion between peers, that blogs can be used as propaganda for your own work, that writing a blog is time consuming and so forth. Cara Phillips pointed out that one problem with blogs and with the internet in general is the constant demand for new content. I agree. This particular blog originally started as a kind of online notebook, one which I had hoped a few other people would be able to contribute to. Before long I was feeling pressure to post new content regularly, as that’s what all the other blogs seemed to be doing. This false need has since subsided for me but I do see it as a problem for blogs.

I can attest, from writing junk for code as a photographer that this kind of blogging is time consuming, whilst the nature oft the blog means that a constant supply of new material is needed in order to keep the blog alive. Limited content means that the blog is dead. As the current ethos of junk for code is to try to deepen the discourse on photography, I mostly avoid simple the practice of quotation and link to other blogs or sites in favour of producing more original and different content.

The problem for blogs that Photographylot sees relates to archives:

If you come to a new blog, how often do you read content beyond the most recent few posts? What happens to all the old posts? As Jorg Colberg pointed out, the accessibility of the archive is key here. Seems like bloggers need to become librarians of their content. As a closer to the discussion, an audience member stated that he thought blogs should exist alongside traditional media but should do what the print media cannot, in that personal opinions, short commentary and analysis can be quickly and widely disseminated, along with images and links to photographers and content that a printed daily, weekly or monthly may not have the space for. In short, blogs are useful and needed to be treated with care, both by their readers and by those who write them.

I'm not sure what to do about the archive problem. It is a problem since, as Joel Colberg points out, most blogs.... are being organized in a temporal way in that new posts are sorted by when they were published - when in fact, their contents usually is not temporal. That makes accessing the archive difficult.

These ideas only scratch the surface of photography and blogging. A more substantive issue would be how to deepen the discourse around photography culture caught up in a technological fetish, favours craft, dislikes aesthetic theory, and works within a decayed modernist aesthetic of beauty as (significant) form.

May 23, 2009

tree + beach shack

Emma Connors in the weekend Australian Financial Review reports on the turn to creative activity as a result of the recession in Australia. The contracting economy it seems, causes people to ask themselves, "Why should I be doing this job and what else would I like to be doing"? It is a very reasonable question, and one I have asked myself.

Connors says that so many are turning to creative writing. People going to writers' festival are no longer interested in just reading. They want to write, and they are seeking information about how to get published. It is a general phenomenon as courses in the creative arts or communication and cultural studies are booming.

It is not just writing----it is also happening with arts and crafts and photography judging by the popularity of Flickr --taking photos and publishing books--what many are calling user-led content creation--or produsers to use Alex Bruns term.

There are limitations to this shift towards various forms of DIY production since, as it is not possible for many to economically survive as a full time writer or art photographer in the marketplace in Australia, and so the creative work can only be done whilst also working part time to earn money to life on. Maybe most photographers will be amateur photographers with real money-making jobs on the side that they don’t tell their colleagues about.

Secondly, large amounts of user-produced content is increasingly being harnessed by corporations (including the ABC re writing) as value added to their services. Will the art industry continue to cling to art’s traditional analog status, to insist that the material, buyable object is the only truly legitimate form of art, as a response to this?

The context of this shift to user generated content is that whilst news photography and photography of all kinds is flourishing professional photographers are suffering---eg., the difficulties facing photojournalism, from street corner news photographers to the deans of the eminent agencies Magnum and vii. Alissa Quart in Flickring Out: Photojournalism in the Age of Bytes and Amateurs says that photojournalists have:

been struggling with downsizing, the rise of the amateur, the ubiquity of camera phones, sound-bite-ization, failing magazines (so fewer commissions), and a lack of money in general for the big photo essays that have long been the love of the metaphoric children of Walker Evans...Yet, paradoxically, visual culture is ever more important. It seems that everyone now takes photos and saves them and distributes them, and that all these rivulets supply a great sea of images for editors to use. This carries certain risks. If they are taking snapshots, amateur photographers are likely not developing a story, or developing the kind of intimacy with their subjects that brings revelation. So what’s the actual photojournalistic value of all of these millions of images now available on Flickr and other photo-sharing archives—so many that they can seem like dead souls?

Professional photographic storytellers are competing with the millions-strong army of amateur photographers whose work is housed on Flickr, which editors cull for cheap or free images, and the rise of amateur-supplied agencies, including iStockphoto—owned by the largest stock agency of them all, Getty Images. There are also outlets that claim to separate the digital wheat from the chaff, like PhotoShelter, a “global stock marketplace,” or the jpg Magazine, which threshes out a few hundred images submitted by Web amateurs and publishes them on paper.

May 21, 2009

Edward Burtynsky: ruins

In exploring the photographic reference points for the Port Adelaide project I reflected that some of my photography was part of a genre of photography that captures the decay we see around us in the run-down, dilapidated parts of the towns and cities that we live in.

This showing the process of industrial decay does not have the same appeal for us as the romanticised ruin ---ie., the "ivy clad" or grown over ruin that we associate with the idea of the ruined or abandoned town or city, such as those of the Maya in Central America that have been reclaimed by the jungle or Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant and the town of Pripyat.

Then I chanced upon the work of Edward Burtynsky. I was much taken by his photographic exploration of ruins that linked back to the Romantics. Only these are the ruins of industrial civilization not those of classical Greece or Rome or the Romantic imagery of ivy clad collapsing ruins:

Edward Burknsky, Shipbreaking No. 27 with Cutter, Chittagong, Bangladesh 2001

Edward Burknsky, Shipbreaking No. 27 with Cutter, Chittagong, Bangladesh 2001

I puzzled over what ruins signified for the Romantics. What was their meaning of the decay? Was it melancholy and monumentality? Arre ruins set in opposition to what the Romantics perceived as the spiritual bleakness of town and city— a "healthy distrust of the metropolis"? Was it an understanding of the world as fragments, as ruins? Did the fragments indicate that this was the limit of our capacity for understanding the world around us?

If ruins for theRomantics signified the contrast between the frailty of human achievement and the immensity and inevitability of nature's triumph, then an exceptions to those are representations of the blasted city in which humanity is directly responsible for the devastation:

Edward Burknsky, Three Gorges Dam Project, Wan Zhou #4, Yangtze River, China 2002

Edward Burknsky, Three Gorges Dam Project, Wan Zhou #4, Yangtze River, China 2002

My responses to this destruction of one city to make for the Three Gorges Dam is a mixture of shock, awe, sorrow, and ironic detachment. There were several cities that were destroyed. Then wondered whether the images of the modern city/ building in decay present us with an appreciation of their fragile, ephemeral character versus the inevitable advance of natural forces associated with climate change.

May 20, 2009

New Topographics in Australia?

I have been looking for Australian photographers who have worked within, or are reworking, the New Topographics tradition of altered landscapes. It is seen as primarily an American tradition --apart from Bernd & Hilla Becher ---even the idea of altered or manufactured landscapes applies to settler society's such as Australia. I'm curious as I'm trying to find Australian antecedents for my Port Adelaide project.

Then I remembered the work of the German–Australian photographer Wolfgang Sievers. He has been institutionalised under under modernism primarily because of his architectural photography. However, his aerial landscapes are intriguing and ambivalent images that offer other possibilities than a modernist celebration of industrial civilization:

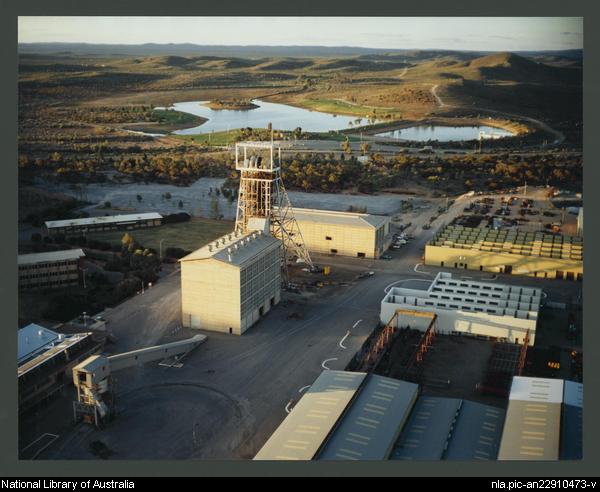

Wolfgang Sievers, Broken Hill, 1980, National Library of Australia

Wolfgang Sievers, Broken Hill, 1980, National Library of Australia

If Australia is a postcolonial nation whose history has been (and continues to be) dominated by social and cultural dependence on other countries, the definition of Australia as ‘provincial’ has been derived from observing local appropriations of other cultures--European or American visual traditions. However, the concern in Australian visual culture is to find a possibility of originality in Australian culture within this relationship of dependency.

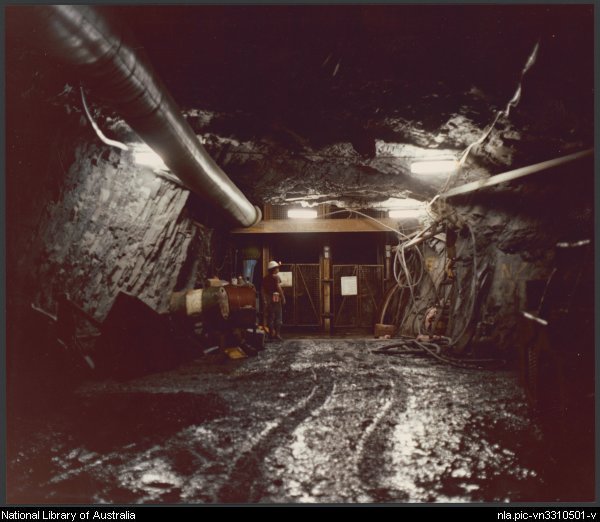

Wolfgang Sievers, Blue Spec gold mine, Nullagine, Western Australia, 1975, National Library of Australia

Wolfgang Sievers, Blue Spec gold mine, Nullagine, Western Australia, 1975, National Library of Australia

Sievers background is Berlin’s Contempora School of Applied Arts (an offshoot of the Bauhaus school), the New Photography and the modernist aesthetic integral to Bauhaus philosophy. However, Siever's work transgresses a formalist modernism as he primarily made his living through documentary commercial work for large corporations:

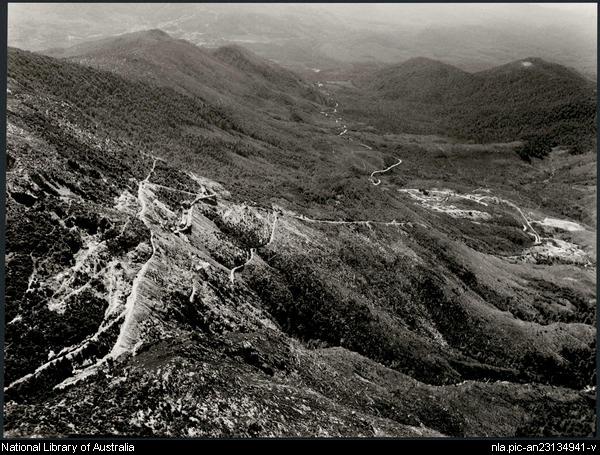

Wolfgang Sievers, BHAS mineral exploration in Western Tasmania near Zeehan, 1959, National Library of Australia

Sievers body of landscape photographic work also challenges the idea of Australia as an unspoiled wildernes since it focuses not on the pristine western landscape of national parks’ wilderness photography but on the “man-altered landscape” by then multinational mining companies. There are many places in outback Australia regardless how remote, where humans have marked nature or wilderness by their industrial presence

Wolfgang Sievers, BHAS mineral exploration in Western Tasmania near Zeehan, 1959, National Library of Australia

Sievers body of landscape photographic work also challenges the idea of Australia as an unspoiled wildernes since it focuses not on the pristine western landscape of national parks’ wilderness photography but on the “man-altered landscape” by then multinational mining companies. There are many places in outback Australia regardless how remote, where humans have marked nature or wilderness by their industrial presence

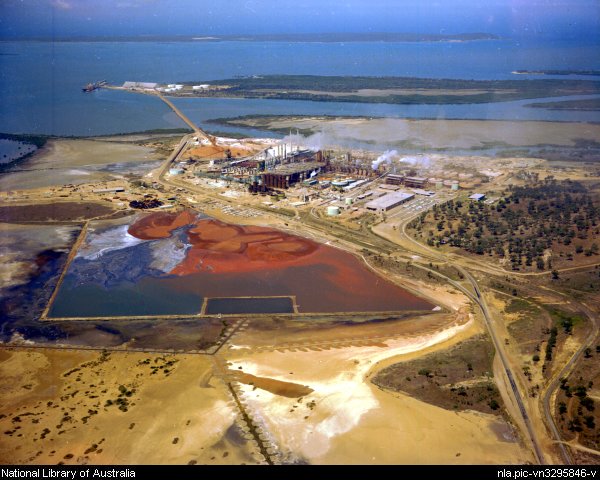

Wolfgang Sievers, Comalco bauxite mine and processing plant, Gladstone, Queensland, 1971, National Library of Australia

Wolfgang Sievers, Comalco bauxite mine and processing plant, Gladstone, Queensland, 1971, National Library of Australia

Is there an irony in this work of Sievers, as there was in the American Topographics movement; an ethical ambiguity about development and wilderness? Irony is a negative trope calculated to expose ideology as distorted representation of reality. Or is Siever's photography transparent documentary. Or is there a juxtapositions of human exploitation and the beauty of the constructed landscape?

May 19, 2009

Naoya Hatakeyama

I read somewhere that Naoya Hatakeyama had been influenced by the American New Topographics movement of the 1970s. The New Topographics was a part of the tradition of documentary rather than formalist photography, and it was related to the idea of 'social landscape', which explores how human beings affect and shape their natural environment. How have their ideas travelled and reworked?

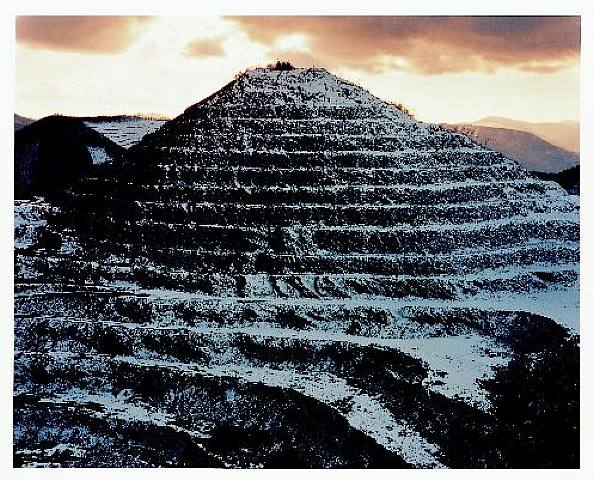

Naoya Hatakeyama, 'Lime Hills (Quarry Series)' (1986-91), Lime Works

Naoya Hatakeyama, 'Lime Hills (Quarry Series)' (1986-91), Lime Works

The claims by New Topographics (eg., by Baltz, Adams, and Jenkins) to scientific objectivity and neutrality were an attempt to disassociate this body of work from the emotionalism and sentimentality of American popular photography. It was also a reaction to what many perceived as the overheated expressionism of the fifties-as represented, for instance, by Minor White-and to the pictorial excesses of the sixties-as represented by Jerry Uelsmann.

The statements were also tacit protests against the contemporary production of images that depicted a traditionally sublime landscape. They chose to underscore the formalist precedents for the work and they pointed to precedents in the aestheticization of the American industrial form in the landscapes in the Precisionist paintings of Demuth and Sheeler, the ironic machine aesthetic of Duchamp and Picabia, the functional stylizations of the Bauhaus, and the conceptual art of the sixties and seventies.

If they allied their work with precedents in art rather than in photography, they were traditionalists in that they recognized the beautiful in the disdained, and they endowed the vulgar and the ordinary with a new pastoralism. They were interpreting the social landscape but from what perspective? The work of Edward Burtnsky 20-30 years latter is fromt the perspective of sustainable living.

Naoya Hatakeyama, 'Lime Hills (Quarry Series)' (1986-91), Lime Works

Naoya Hatakeyama, 'Lime Hills (Quarry Series)' (1986-91), Lime Works

Another reworking of this tradition is that by Naoya Hatakeyama, who is is one of the most important Japanese photographers of his generation. He says in this interview that he is not interested in a photography that takes pictures to document interior space, where interior space” refers to a concept of the self and connotes a sense of this warm, fuzzy feeling of beauty inside. He prefers to pay more attention to the exterior world and his photographs are a form of visual poetry. He has a major following in Germany because of the influence of the Bechers, with whom has thematic affinity.

Lime Hill (Quarry Series) (1986-1991) and Lime Works (Factory Series) (1991-1994) are landscape photos of Japanese limestone quarries and of the mining industry. The Lime Works series represents the transformation of the landscape through limestone extraction for the production of concrete, the material Japan’s fast-growing cities are built of. The limestone is removed on roads concentrically paved around the mountains; the quarries forge ahead further and further into the mountains; the landscape changes. For Hatakeyama this rough landscape, from whence the raw material for cement is dug, is the first phase of urbanism. The holes that are gouged in the earth reflect the buildings in the cities.

May 18, 2009

salt lake, near Lake Alexandrina

I managed to get way to Lake Alexandrina yesterday. Suzanne went sky diving in the early morning near Lake Alexandrina, and we spent the rest of the morning and the early afternoon exploring the northern edge of Lake Alexandrina.

This region of the Murray-Darling Basin does not have a healthy future --economically and ecologically. Many people still have a strong belief---faith--that enough rain will arrive and save the situation, even though natural science says otherwise.

Others claim---eg., the River, Lakes and Coorong Action Group (RLACAG) ---that water is available upstream and can be supplied in time to save the lower lakes and Coorong. If there is no such water available (and catchment inflow data indicates there isn’t) and the scientists and government advisors are right, then the RLACAG freshwater only position is untenable.

My concern on this brief trip was to start using the Linhof Technika 70 with its 6x7 and 6x9 film backs to explore ways to photograph this very flat landscape on the ground. The problem was a formal one: the best way to construct the landscape so that I could then start using a view camera and sheet film.

I used the digital camera as a kind of sketch book and took some exploratory shots with the Linhof 70 and the 6X7 film back. Focusing on an upside down image on a groundglass is slower than through the viewfinder of an digital camera or a Rolleiflex SLR, but I got used to fairly to it quickly even though I hadn't done so in a while.

May 17, 2009

Dirt Game

I've been watching the ABC's href="Dirt Game---a six-part, locally produced, drama series-- to see if free-to-air television is beginning to arrest its downward slide. It is seen as Australian drama with sophistication and depth. It is on the ABC"s prime 8:30pm Sunday night spot for quality drama.

It does make a welcome break from the BBC costume drama and the pacing, photography and writing are a definite cut above the standard local productions that are kitsch, and it holds its own with overseas productions from the BBC. It also affirms that television is about photography as much as it is about writing and acting.

Several episodes in and I'm more critical.This is a very progressive mining company on issues such as the environment, worker safety, and negotiating with aboriginal people. It is always on the brink of collapse and its mining operations are old, run down, economically marginal, and always in danger of not being able to deliver its orders. We go from crisis to crisis with the world of commerce divorced from politics.

The economic reality is that mining companies constitute Quarry Australia, are the most powerful companies in Australia, have some of the biggest mines in the world, fueled the decade long boom, and oppose the changes needed to deal with climate change and truck with junk science.

May 16, 2009

Yoko Ono + photography

Yoko Ono was a conceptual and performance artist with her roots in the Fluxus movement who was part of atonal avant garde on the margins of in rock music. Her work spans music, performance, writing, painting, installation and sculpture.

A recent work, Imagine Peace Tower, was envisioned in 1967 by Ono as a sort of conceptual “light house”. The monument, now located on Videy island, near Reykjavik is comprised of a large, cylindrical “wishing well” structure adorned with the phrase “Imagine Peace” in 24 languages that projects intense beams of light skyward to form a temporary “virtual structure” similar to the memorial twin towers of light once projected at Ground Zero in New York.

An earlier work, Greenfield Morning (I pushed a Baby Carriage All Over the City) from the 1970's Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band.

I'm interested in the way that Yoko Ono used photography in her art. My starting point is Yoko Ono on Fickr and this Artwork set. The approach to photography is conceptual, and so focuses on the way that we relate to photographs.

May 15, 2009

The Who: Who are you

The Who's final album with Keith Moon was not one of their best. It was the last reasonably interesting Who record. Part of the genesis Who Are You is another attempt to revive the 1970's Lifehouse project. The film footage of the band apparently recording this song was filmed at Ramport Studios in June, 1978

I've always liked/enjoyed this song. It is a long way from the volcano of violence on-stage, teetering on the edge of chaos but never blowing apart, but the core of The Who was always Townshend, the band's guitarist and main songwriter.

I stopped listening to the band with Who's Next. So I haven't heard the recent Endless Wire. Strangely Greil Marcus was kinda impressed at the time.

Townshend has said

"'Who Are You' was written about meeting Steve Jones and Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols after an awful 13-hour encounter with Allan Klein who, in my personal opinion, is the awesome rock leech-godfather. In one sense the song is more about the demands of new friendship than blood-letting challenge. Roger's aggressive reading of my nihilistic lyric redirected its function by the simple act of singing "Who the fuck are you..." when I had written "Who, who, who are you..."Steve and Paul became real 'mates' of mine in the English sense. We socialized a few times. Got drunk (well, I did) and I have to say to their credit, for a couple of figure-head anarchists, they seemed sincerely concerned about my decaying condition at the time.

Cook and Jones, supposedly arrogant young punks working out their rock & roll Oedipal complex, were thrilled to meet Townshend and horrified at what he had to tell them: the Who were finished, used up, wasted. The incident left Townshend passed out in a Soho street, which is where the song begins. Townshend (in the voice of Roger Daltrey) wakes up with one enormous question: Who are you?

May 14, 2009

The Gruen Transfer's anti-discrimination ad

Each week at The Gruen Transfer two of the advertising industry's agencies are pitted against each other and challenged with selling the unsellable.This week one ad on the anti-discrimination brief about discrimination against fat people did not go to air as it was not approved for broadcast by the ABC.

The Gruen Transfer's blurb states:

This segment of The Gruen Transfer was scheduled to appear on the ABC-TV program on May 13, 2009. It was not approved for broadcast by the ABC. We are grateful for the ABC’s consent for us to put the material on this website, as it facilitates further debate and discussion.This is a confronting ad. We at Gruen feel that it may be offensive to some people, but we stand by the fact that The Foundry agency made it with a considered and legitimate intent to persuade Australians to reconsider their prejudices.

The video from The Foundry is here. It is followed by a serious discussion on the effectiveness of the ad's shock tactics to challenge people to recognise that discrimination comes in all shapes and sizes and that discrimination against fat people in the form of jokes is similar in kind to racist jokes.

May 13, 2009

haphazart magazine

The first issue of the Haphazart magazine is out---- it is produced by self-entitled freaks, fools and pranksters! It looks good in terms of the magazine reflecting the origin of this very interesting and highly active Flickr group. There is more about the magazine on pa gillet's blog, if you can read French. You can buy the text from Blurb. I recommend that you do so as this is one of the strongest groups on flickr.

The cover image is by Dom Ciancibelli whilst the Editorial Team, who gave up their free time to produce the magazine, consisted of:

Content Development - Christian Kinzler (tossthecam)

Text - Mark Sullivan (mark valentine)

Image Selection - Krystina Stimakovits (casually, krystina)

Design & Layout - Shari Baker (floebee)

On a personal note two of my photos has been included. I submitted this and this. However, I'm not sure what purpose they serve, or what point they illustrate, in the article by Mark Valentine.

The featured artists in the Haphazart magazine are PA Gillet (pa gillet;) Krystina Stimakovits (casually, krystina); Dom Ciancibelli; Mike Lusk (finsmal); Christian Kinzler (tossthecam).

There are two articles in the magazine. One is by J Neuberger entitled Haphazart! Contemporary Abstracts. The other is Searching for a Theme edited by Mark Sullivan (mark valentine). I'm not sure what they argue in these texts, since the Blurb book preview only allows you to preview the first 15 pages.

However, Mark says that his text is actually an edited version of a topic from the haphazart group - the searching for a theme thread that is entitled theatrical therapeutic thematics. In this thread it is argued by casually, krystina that:

[I've] always thought the photographer's task was to make some kind of sense or create some kind of order from the mass of visual information around..I think nothing is easier than just to shoot whatever comes your way regardless how. In fact there are thousands or millions of images just like that here on flickr. Nothing wrong with that in principle, if all people want to do is to simply share whatever they see at any or every moment of their spare time....and clearly there's room for that, but even someone like Winogrand who could shoot thousands of images every month, would in the end....(usually 3 years after shooting) make a careful and critical selection of his material.

Well that is true. Photography is an interpretation of a selected bits of the visualscape we find ourselves within. An interpretation that works within historical design conventions. casually, krystina continues:

For anyone interested in image making will sooner or later ask themselves what it is that makes an image arresting or memorable or evocative. To a large extent there will always be a mystery about that, however such images do tend to have some things in common....i.e. they have been 'composed' ...and composing means making sense or creating some kind of order of what we see - and it does not matter whether this was done intuitively or consciously. In a world where most of us are bombarded by a constant flow of images don't we want to try for our images to stand out just a very little, so that MAYBE someone spends a little more than just one second looking at it?

This introduces different styles of working photographically: ---- one working by chance or indeterminacy when we walk around the streets of a city or a landscape, or working on a specific project within specific boundaries. such as the Port Adelaide one.

The former, the haphazard one, has its roots in the Fluxus movement. However, I'm not sure whether these roots are explored, or in what depth. But it does leave us with different ways of working on the table. to mull over.

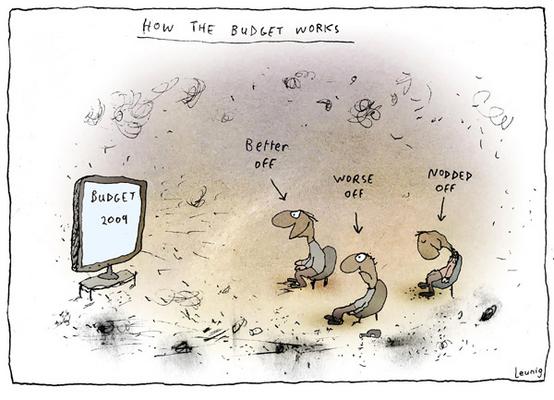

no creative economy

There was no arts led recovery in the Rudd Government's Budget 2009. The creative economy has little profile in Canberra---the big spend on the credit card is all about infrastructure in the form of roads, rail and ports. An exception is money to increase in the capacity of Adelaide's desalinisation plant, rather than water recycling.

The exception to the absence of the creative economy is extra money for the ABC to build a children's digital channel and the production of local drama production by independent producers. But no digital news or public affairs channel. That is the future.

The regional broadband hubs will host community generated work that is centred around the ABC's regional radio. I'm not sure how this works since those in the community who want to upload material will need to be trained in digital skills and literacy.

Kozloff on photographic criticism

Max Kosloff in his Critical reflections - photographic criticism in American SuburbX makes two points. The first is that photos witness events, with its implication of documentary as opposed to trace:

my criticism was gradually drawn to the contrast between the photograph's nominal and effective content (in Roland Barthes' terms, studium and punctum). The former is usually indicated by the image's social or technical idiom, and the latter is brought out by a wild power to shock, disturb, or touch a viewer, sometimes constructed by artistic design, but more often generated through a fortuitous or maybe inadvertent detail captured within the picture's socialized program. Barthes has written of the detail as a feature that he detaches from the pictorial field through his unsharable private subjectivity. Not only is this ungenerous, it's mistaken, because the unaffecting genre material and the moving detail are indivisible. Photographic images are haunted by the sheer doggedness of the random. I suspect that this is another way of saying that the world has its unpredictable way with them. The world is strewn with obscure, uncalled-for particulars, which mingle indifferently with our programs and our stories. But as photographs blend these particulars in spasmodic ratios, miscellaneous jolts and narrative import are all part of the picture.

'Trace', in contrast, implies references which have become detached from their source, circulating in new contexts, but with something of their origin continuing to adhere.

The second is that:

The idea that texts are somehow superior to images (as if they could be ranked) sounds crazy to me, but this idea is widely assumed - and goes unquestioned - in academia. In the sociology of higher learning, those who study the visual arts are placed on the bottom rung of an intellectual hierarchy. Literary critics, semioticians, and political scientists, role models all, may be asked to lecture to art historians, but not the other way around. Wishing to improve their status and to blend in, those in the image line could distance themselves from visual objects in their increasingly theoretical work. It says a lot about their approach to the image that they canonized Duchamp, more renowned than any other twentieth-century artist for his animus toward the visual. It says even more that they stamped out pictorial allusions and therefore descriptive appeal from their language, one reason for the abstract tenor of their writing. Suitably deadened in tone, it gained prestige in the semantic environment of grad-student seminars.

May 11, 2009

Port Adelaide project

I've begun work on the Port Adelaide project that I mentioned in this earlier post. The project, which pushes to an e-book --- is being developed in the context of this new Flickr group---Port Adelaide character that has just been started.

The Port Adelaide Character group has a historical heritage perspective that assumes an “enclave” model of the Port: the Port is a where people can live, shop, work, and “spend their lives, in a matter of speaking” — “a community that essentially is separate and can stand on its own feet.” This model works in opposition to, and is opposed by, the commerce model, which makes the urbanscape and community entirely subordinate to the interests of industry and, which is oriented toward the maximization of land values, building density and profit.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, storm water, Port Adelaide, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, storm water, Port Adelaide, 2009

My own perspective is close to that of David Harvey, who argues that urbanization has been intimately tied to the growth of global capitalism.

A capital surplus means that it needs to be invested it--the capital absorption problem. There are all kinds of places it can go but one of them is into the production of space and new forms of urbanization. That is what is happening in Port Adelaide now with its re-development.

May 10, 2009

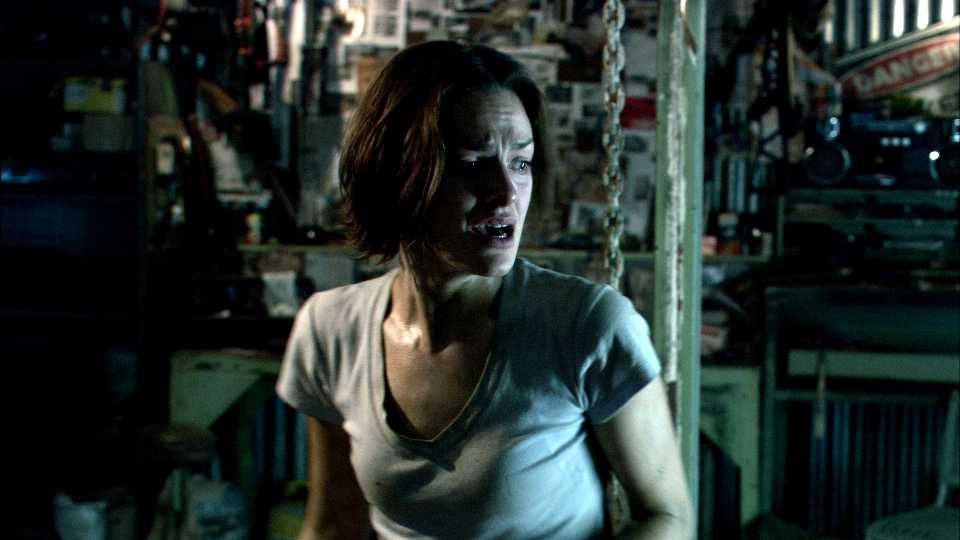

Wolf Creek

I started watching Wolf Creek on free-to-air television last night. I tossed it in just before the halfway mark because I couldn't stand the interruptions from the advertisements. I'll watch the low-budget horror in the desert film on DVD latter.

I was curious by the commentary about the film being loosely based on Australia's "Backpacker Murders," (false), its debt to the hugely influential "Texas Chainsaw Massacre", the dystopian view of Australia's Outback that is in such contrast to the tourism industry's selling of Australia and the way it subverts a mainstay of Australian outback mythology - the noble white bushman, the loveable rogue.Mick Dundee, Crocodile Dundee, gone real bad.

I saw enough to see the film's unusual narrative structure: a steady, drawn-out first act that establishes the trivial realities of the characters’ and their relationships with one another, followed by a violent, climactic second half. The film's generation of tension and suspense through the cinematic representation of violence would have been completely destroyed by the advertisements.

May 9, 2009

beauty: a note

Arthur Danto in his book The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and the Concept of Art makes an important point: "Good art may not be beautiful." As he put it: "I regard the discovery that something can be good art without being beautiful as one of the great conceptual clarifications of 20th-century philosophy of art."

This directly challenges aestheticism, which holds that regards beauty as an end in itself, and attempts to preserve the arts from subordination to moral, didactic , or political purposes. This term is often used synonymously with the Aesthetic Movement, a literary and artistic tendency of the late 19th century which may be understood as a further phase of Romanticism in reaction against philistine bourgeois values of practical efficiency and morality.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, rose, Solway Crescent, Victor Harbor, 2008

Gary Sauer-Thompson, rose, Solway Crescent, Victor Harbor, 2008

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the creation or representation of beauty was one of the aims and prerequisites of art. Within fifty years this status, as it had been known, was erased by the avant garde. On some accounts the impulse of modern art is the desire to destroy beauty in the sense of ornamentation or prettiness or pleasant.

Beauty is decentred as a value, and it is effectively exiled to the fashion world (and hairstyling and cosmetics) where it reigns supreme as artifice. Beauty for Vogue is about concealment, disguise; it's about how to manufacture appearances an art of sexual allure. Does that mean, for modernism, that the "turn away from beauty" in modernism is inevitably connected to gender politics?

Is it possible, or desirable, to reintegrate beauty as a value into our thinking about art and about life in general? The standard response is to locate beauty firmly and completely in the eye of the beholder. Beauty is wholly subjective, in that it is a pleasure of the viewer rather than an aspect of the things that give rise to pleasure. Beauty is all in the head.

May 8, 2009

thinking images?

I've always puzzled over the idea of 'thinking images'. It suggests an image that goes beyond poetics and style to become a thinking work. What is a thinking image or photograph? Is it a going beyond poetics and style to become a thinking work.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, grid, Adelaide CBD, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, grid, Adelaide CBD, 2009

The Thinking Pictures issue of Image and Narrative explores this puzzle of pictures that think. Is it one that suggests a possibility of alternative meanings and interpretations? Is it slapping a title on the image to open up the different interpretations by critics?

I can get the idea that an image shows two faces---a construction site that is also a ruin. That takes us to possiblities of the idea of dialectical image that can be found in the writings of Walter Benjamin and Theodore Adorno. I've always been puzzled by that. Anthony Auerbach explores this in Imagine no Metaphors: the Dialectical Image of Walter Benjamin

May 7, 2009

rephotographing Agtet

Photographer Christopher Rauschenberg, the son of artist Robert Rauschenberg, and founding member of Blue Sky Photographers Collective and Gallery did a rephotographic project in the 1990s on Atget's photographs of Paris. There are some of Atget's pictures on earlier posts on junk for code.

This body of work has been published in book form as Paris Changing and Lens Culture has an article on this project.

Christopher Rauschenberg, Rue des Ursins, 199, silver gelatin print, from the series Rephotographing Atget

Christopher Rauschenberg, Rue des Ursins, 199, silver gelatin print, from the series Rephotographing Atget

You can see Eugene Atget's original photo on conversations. Rauschenberg says of this project that:

As I was rephotographing Atget images, I kept seeing places that he hadn’t photographed but that seemed to me to be also rich with the feeling of his work. I photographed hundreds of those places where I felt Atget’s spirit. Included here are just six of them. I don’t claim to have been channeling Atget, or that Atget would have photographed those places were he to see them. I was walking around Paris “in Atget’s shoes” and this is where they took me.

Lucky fellow. We could do the same in Australia couldn't we?

May 6, 2009

Dylan: Like a Rolling Stone, 1966

This is Bob Dylan and The Hawks as they were then known (they became The Band latter) playing "Like a Rolling Stone" live in 1966 in England. It's a raw and angry version. The sound quality is quite good though the filming is below average. The song is part of one of the most famous and legendary performances in the history of rock music--known as The "Royal Albert Hall" concert---and it was often bootlegged before the official release.

The first part of the concert at The Free Trade Hall was Dylan doing a solo acoustic set that featured songs he had written over the past 16 months to a reverent audience. The second part of the concert was an electric set to a hostile audience.

I personally don't much like the folk set of this concert. It feels kinda lifeless to me, even if Dylan does play with his audience's expectations of Dylan as folk singer. But this electric track is good--nay, classic--rock and roll.

A report on a Dylan conference in 2005 at the University of Caen (Normandy, France) by Christopher Rollason. I find that most of these type of academic conferences that present work in the form of Dylan criticism over-emphasis the lyrics rather than music. The literary culture certainly values Dylan highly---and rightly so; but Dylan is musician as well as a poet who records albums in a studio and he performs the work onstage in front of an audience as Dylan the superstar.

This video clip is about the performance.

May 5, 2009

beyond Flickr

I'm increasingly coming to see Flickr and its diverse groups as an digital archive composed of various photo streams. At the end of the day all you

have to show for their extensive work is a huge file of images.

How then do you move beyond the archive and the photo stream and the photoblog? How do you build on the community of photographers that gather around the different groups.

Gary Sauer-Thompson, painted twigs, Melbourne CBD, 2009

Gary Sauer-Thompson, painted twigs, Melbourne CBD, 2009

There are several pathways out from the digital archive of images. The most popular is the online magazine that is based on submissions. Another is online exhibitions done by the altfotnet.org group. The third is the digital book using Blurb or other self-publishing software such as Lulu. A review of the photobook publishers that one can use.

The publishers have software you can use, the books are professionally produced, and they give people the opportunity to create extremely small runs as the books are printed to order. Lulu, VioVio and Blurb offer you the option of selling your book creations online. With Blurb once you publish your book you only need to order one copy within the first 15 days for it to stay in the bookshop.

May 4, 2009

Canterbury plains

This is the last picture from the recent New Zealand road trip from the work produced with my digital camera that will be uploaded to Flickr. It is the greenery of the Canterbury plains and water of the Rakaia River that immediately jumped out for someone living in Adelaide, South Australia during a long drought.

There are still some pictures of the exploratory road trip that I shot on film (using a Lecia for 35m and a Rolleiflex TLR for 6x6), which I have yet to have processed and scanned by the lab (I do not have a scanner). I have to save the money up now that I've ended the full time Canberra policy wonk contract.

I'm back in Adelaide with more time on my hands. I'm currently picking up on the Port Adelaide project from where I left off. I want to link it more within the New Topographics tradition of the 1960--70's; or rather to situate the project as a contemporary reworking of that initial American exhibition.

A contemporary example of the New Topographics photographic tradition can be found in this echo of the original altered landscape style. The The Exposure Project blog says that:

In the 30 plus years since this exhibition took place, the expansion of residential and industrial development has continued to rapidly sprawl to meet the demands of our global community. Many contemporary photographers have picked up where the "New Topographics" artists left off, weighing the effects of consumerism on the environment and the culture

Ben Alper, who writes the blog, and picks up where the "New Topographics" artists left off through exploring the anonymity of the American industrial landscape. He says:

These structures were erected in a utilitarian and institutional fashion, however, they have outlived their commercial use and been abandoned.....These industrial expanses are easily overlooked. Often isolated on the outskirts of cities and towns, these areas are largely uninhabited and unfrequented. The stark absence of people in these photographs emphasize the barrenness and anonymity of these places. Even so, there is a pervading sense of humanity in these images.... Now discarded, the context has changed, and the interactions between people and these spaces has changed with it.

That is what I am finding at Port Adelaide. It is in transformation with the new waterfront housing redevelopment. The old is going.

I want to shoot some of the pictures in the Port Adelaide project in a more deliberate fashion using the ground glass style of medium format camera (using my very old and battered Linhof Technika 70.) This is a desire to return to the more deliberate style of photography of large format photography (and to eventually start using the even older 5x4 Linhof).

This is a way of working that is premised on using the digital camera more as a sketch book that gives me a body of images, which I can then select particular images and then work slowly on them using a dark cloth, ground glass and flexibility of a large format camera.

May 2, 2009

Alfotonet: One City; three Views

The second online exhibition at Altfotnet.org is now up. It is entitled One City; three views I am still writing the text on the figure of the flaneur and photography. I have just finished a draft for the first exhibition --concrete canvas which you can read here.

Update

The National Library of Australia has been given a copyright licence to include alfotonet.org in the PANDORA Archive. It is publicly available in the PANDORA Archive here.

Access to your publication in the Archive is facilitated in two ways: via the Library’s online catalogue; and via subject and title lists maintained on the PANDORA home page.

May 1, 2009

Velvet Underground: Loaded

I picked up a CD of the Velvet Underground's most commercial sounding album Loaded a while ago. It was the last album (1970) they made before Lou Reed left in frustration and disillusionment and the band effectively broke up. Funny enough I haven't played it until just recently. A Rolling Stone review from the 1970s.

Loaded is a long way from the toughness and rawness White Light/White Heat (1967), which is an expression of avant-garde rock'n'roll. It is commonly assumed that the Velvet Underground were the cutting edge of rock music in the late 1960s.

Parts of the up-tempo rock'n'roll of the Loaded album presage Lou Reed's subsequent solo career---namely, 'Sweet Jane', "Rock & Roll" etc. Ironically, The Velvet Underground begun to acquire popularity and their iconic rock status a few years after they broke up. Despite Reed's strong songs (eg., "Cool it Down"). Loaded does fall short of the previous Velvet's albums in terms of musical accomplishment. An example is "Lonesome Cowboy Bill".

If the Velvet Underground were once an expression of the avant garde in rock music, then this album is not an example of it. The experimental impulse that emerged out of Warhol's staged theatrical multimedia happenings---Exploding Plastic Inevitable---has long gone.

Update

I've been listening to the Second Disc of the Fully Loaded CD version, which has the rougher or alternative versions of the songs, where the Velvets sound much more like a garage band with its two-guitars/bass/drums lineup.The idea behind Loaded now comes more into focus: it both explores the form of commercial or pop song from the perspective of different musical styles and subverts the commercial song.

You can also hear Lou Reed the individual performer on these outtakes and demos. These were subsequently used by him for his subsequent solo albums such as Lou Reed, the Bowie produced Transformer and Berlin.

I have yet hear any of the live work of the band--other on YouTube-- or the lost album that is known as VU, which was based on previously unreleased tracks that were made between the third album The Velvet Underground (1969)-- after Doug Yule had replaced John Cale--- and Loaded (1970) --the last one.

Update 2

I have little knowledge of the texts about the Velvet Underground. The text, The Velvet Underground Companion, collects reviews, interviews with band members and critical commentary. I have no idea what is the best book on the group in the context of Warhol, music and image. Is it this one? The photography looks interesting.

One text that I do know is Mark Grief's review of Richard Witts' book 'The Velvet Underground' in the London Review of Books of Richard Witts' book 'The Velvet Underground.' It is entitled The Right Kind of Pain- and raises the avant garde issue.

Witt says that the 1960s Velvets manifested atavisms of the 1950s that had survived in the New York art-world. These fused a 1950s Beat-existentialist sensibility (acquired by Reed at Syracuse University) with a recycling of the 1910s and 1920s avant-garde (learned by Cale from Fluxus artists in New York). It was ‘the confluence of a songwriter imbued with 1950s existentialism’ and ‘an arranger attracted to the performative actions of neo-Dadaism’.

Update 3

In re-reading Grief's article I notice that Witt adds to the avant garde heritage by pointing out that John Cale was the main avant garde figure. Grief says:

Everything Cale brought to the band, technically and philosophically, was taken directly from LaMonte Young and his wife Marian Zazeela. Young and Zazeela were coterie-oriented avant-gardists who wanted to advance music and liberate minds through new instrumental means. It’s not unusual to identify Cale with the avant-garde, nor with Young, his teacher, but it’s pretty shocking to be told that Cale’s Velvets-era avant-gardism was really nothing but Young’s techniques.

The classical avant-garde even today is sometimes content to play down the pain, annoyance, boredom and nuisance of the willed adherence to dissonance, atonality, minimalism and extended settings which were hallmarks of many of its best effects over the last century. You are supposed to be a good and educated listener, which means listening through annoyance for transcendence.

The Velvet Underground, however (in Cale’s revision of LaMonte Young, and in his new partnership with Reed), was able to reposition avant-garde annoyance and aural pain as part of a thematics of being bad. They aimed to hurt your ears with the newly available techniques, and to match this effect to an ethos of pain in the lyrics so that it all made sense.