|

February 07, 2007

Where it once shocked as the new in the early 20th century, cinema now saturates our habitual ways of seeing. The shock of the new has given way to acceptance and naturalism. Yet the experience of cinema has remained intensely ambivalent since film is is neither wholly real, nor simply imaginary (as those terms have been customarily understood). The history of photography and film (and the mass media) has produced an image-world where representation is no longer shaped to fit what is real; but rather the world is called on to live up to its images. So how do you represent the horrors of history?

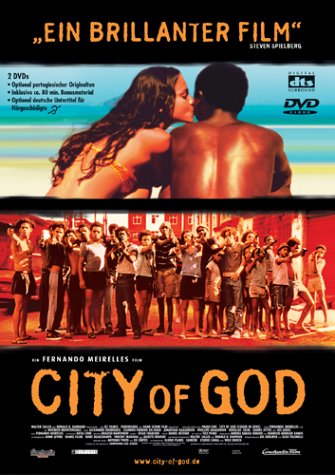

I watched the Brazilian gangster film The City of God (2002) by Fernando Meirelles on the weekend. This represented the horrors by reworking the modernist concept of history conceived as a narrative series of motivating causes and effects to depict the rise of dystopia within the very heart of modernity.

In the filmRocket, a photographer, narrates our journey into the slums of Rio de Janeiro. A child of the 60s, he witnesses two decades of barbarity, greed, rape and revenge which fuel a catastrophic gang war and the rise of Li'l Zé, a ruthless, sociopathic killer, as the ghetto's 'godfather.' The film is trading on something actual: the dirt-poor Brazilian housing project Cidade de Deus, on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, which was created in the sixties, and quickly became a highly dangerous fiefdom of teen drug lords and gang chieftains.

The film, which was adapted from a best-selling novel by Paulo Lins who grew up in Cidade de Deus, depicts an amoral slum world without pity, where children casually kill children. Poverty and depravity have stripped these kids of any defining humanity and turned them into a race of grotesques. The experience of the slickly presented violence centred on the pleasure of the look is one of shock; even though it is easy to accept the idea of history as biodegradable ---it is very selective, full of gaps, as it is formed by processes of selective amnesia, illegibility, repression, avoidance, neglect, and loss. That shock does not lessen even though the photographer is redeemed through art for we are left with a nightmare akin to an inferno.

I know very little about Brazilian cinema, let alone the cinema of Latin America. My vague conception is that it is politically orientated. The cinematic experiments and activism of the decades of the 1950s and 1980s is about revolution, dictatorship, and exile constitutes what a Latin American 'cinema' has most generally been identified with both in film exhibitions outside Latin America. I have no knowledge of Latin American cinema studies in English.

What is only implied in the film is the way that a the legacies of hundred years of American and European economic and political imperialism have created unequal development, high rates of urbanization and the concentration of wealth in the hands of the Brazilian elite and international investors, and the socially excluded poor who limited access to education and better jobs. Over 500 shantytowns or slums, (known as favelas,) exist within the confines of Rio de Janeiro, comprising more than a third of the city’s population. The everyday violence of Cidade de Deus is a result of this underlying, historically entrenched, structural and political violence.

Although Rocket photography gets him out of the slums there is little that indicates he'd been able to see something through the lens of his camera that he couldn't as a mere bystander. He doesn't seem to think about the meaning of the violence that he captures --he's a newspaper photographer. There is little reflection on the role of art in representing the horrors of history, or about the eye or visuality, or with light as a metaphor for the desire for truth (Plato and the cave) Is the film part of a truth-system structured around the light metaphor (light in terms of enlightenment)?

|